PAUL WILLIAMS: A GIANT TALENT

In Our Vintage Interview, Williams Talks with PCC About Songwriting, Acting and Recovery

By Paul Freeman [July 2002 Interview]

Paul Williams is a man of many talents. He's also a man of tremendous resilience.

The lyricist/composer is himself a distinctively expressive vocalist. But Williams has had the pleasure of hearing his songs performed by such diverse greats as Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, Barbra Streisand, Three Dog Night, Ella Fitzgerald, The Carpenters, Tony Bennett, David Bowie, Willie Nelson, Diana Ross, The Dixie Chicks, Jason Mraz, Sarah McLachlan, The Monkees and Kermit the Frog.

His honors include an Oscar, three Grammys, two Golden Globes, the Ivor Novello Award and induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

Among his many unforgettable hits are "Rainy Days and Mondays," "We've Only Just Begun," "You and Me Against The World," "Evergreen," "Old-Fashioned Love Song" and "The Rainbow Connection." He also wrote the music for the film "Bugsy Malone."

Williams also has enjoyed success as an actor. He was seen as Little Enos in the "Smokey and the Bandit" movies. His many other credits include "Battle for the Planet of the Apes," "The Wild, Wild West Revisited," "The Muppet Movie" and "Baby Driver." He made a lasting impression as the diabolic record producer Swan in the cult favorite "Phantom of the Paradise," for which he also wrote the music.

He has openly discussed his struggle to overcome alcohol and drug dependency. Now sober for decades, Williams penned the book "Gratitude and Trust: Six Affirmations That Will Change Your Life" (co-written with Tracey Jackson).

The documentary "Paul Williams Still Alive" depicted his life, career and work as a recovery advocate.

We spoke with Williams, the Chairman of the Board of ASCAP, before a 2002 University of San Francisco concert teaming him with Kris Kristofferson.

POP CULTURE CLASSICS:

It seems like you're reenergized, when it comes to making music.

PAUL WILLIAMS:

I've been sober 12 years [he said in 2002; it's 28 years as of this writing, 2018] and pretty active in recovery. But when I first got sober, I was 49 years old. I always said that I didn't have the best childhood, but I had the longest [chuckles]. All of a sudden, I was like, God, can I do this?" The one place I felt safe was around recovery. So I went to UCLA, spent a year there and got my certificate as a drug and alcohol counselor. So I guess, about three years, I worked as a counselor, as a volunteer, traded my hours for a bed.

And part of what grew out of that, is I became involved with Buddy Arnold, who has an organization called the Musicians Assistance Program, which has put, to this point, hundreds of musicians who couldn't afford it in treatment. But somewhere along the line, my wife started shoving me towards the front door, going, "You're a songwriter. Aren't you going to do that again?" I said, "You know what? When I fall in love with it again, I'll do it."

"The Muppet Christmas Carol" was, I think, like '92. I wrote the songs for it and produced it, got nominated for a Grammy and went, "Boy, it's just gone. The passion's gone." But about four or five years ago, I went down to Nashville... and there's something in the water. I kind of fell in love with the process of writing again. It's a slow walk back from that.

Jimmy Webb called me last fall, actually right before 9/11 and asked me if I wanted to Feinstein's in New York with him for three weeks. I said, "No." I was just like, uh-uh, I didn't want to do that. A friend of mine who lives in New York said, "You're absolutely crazy. It's the most coveted gig in New York. It's a great club. And blah-blah-blah. And you're going to get a lot of attention." My wife wanted to go spend November in New York. And, you know what? I had a really good time. [Laughs] It was like surprising -- two old guys, two geezer songwriters, him doing these wonderful old songs of his and some new ones, and me dragging out the co-dependent anthems I've become famous for. And it was just a lot of fun.

So yeah, I'm doing a little bit. I've got some symphony dates that I'm doing. I'm actually going to go down to Mobile, Alabama for six weeks starting the middle of August with Brad Renfro and Barbara Hershey, Randy Quaid, a little picture called "The Vacation." I'll be acting in that. I've got one coming out in October called "Rules of Attraction," which is Roger Avary, the guy that co-wrote "Pulp Fiction." He wrote and directed. So I'm real pleased with that.

The other thing that's new and current, as I kind of blah-blah, trying to give you an update on my life, is "The Sum of All Fears" [the Ben Affleck Jack Ryan film] -- Jerry Goldsmith and I wrote the title song for it, which Yolanda Adams sings ["If We Could Remember"].

PCC:

Beautiful song. We were walking out of the theatre when the credits came on, heard it and walked back in.

WILLIAMS:

Oh, did you really? How lovely. You're the one who heard it all the way through then.[laughs].

PCC:

You also have a relatively new album.

WILLIAMS:

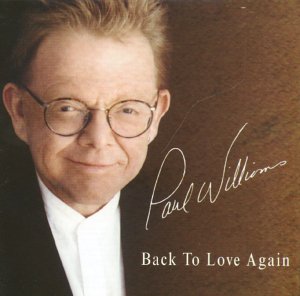

Well, I did one about three or four years ago in Japan that they just released in this country, called "Back to Love Again." You know, to me, there's something pathetic about a little old man going out in the streets, going, [in his best "Oliver" accent] "Please, sir, can I have some more attention? Please sir, can I have some more?" Groveling for that little extra bit of attention and fame and success or whatever. I don't have a press agent. I fired the agents. And as soon as I fired the agents, I got a couple of extra jobs [laughs]. It's really weird. There's a part of me that's kind of really just throwing myself on the fires of gratitude and trust. And I'm just having the best time.

PCC:

When was it that you went back to UCLA and studied to become a counselor?

WILLIAMS:

'91. I've been sober since 1990. I actually had my last drink in '89. But March, 15, 1990 is my official sober birthday, when I began to experience the huge difference between waking up and coming to... when I was given this great gift of recovery. And the real gift in going to UCLA and spending the time there is I found out that it's not about willpower and we're not bad people trying to be good people. I have a disease. And I don't know when I crossed that line, from use to abuse to addiction. But my guess is that it was probably in my late thirties. And I was so productive in the 70s, the Oscars and the Grammys. I was nominated for six Oscars and won one. And then you look at the 80s and, essentially, I did one movie. And that was "Ishtar." [Laughs]

What happened? What was the major change in your life? You go from the kind of productivity you had in the 70s to hiding out in the 80s. Because, essentially, I was hiding out. And I think that the real gift is to be able to sit down with a bunch of kids in a school or whatever and say, "Your dad and mom know who I am. And you don't. The reason is drugs and alcohol." So, if I can use it like that, I do.

PCC:

But why did you become disillusioned with the music?

WILLIAMS:

Well, it wasn't disillusionment with the music. It was the terror of, "Can I do it without the drugs?" The drugs became such a huge part of the lifestyle and, I thought, part of the writing experience. I mean, it's clear now that I wrote in spite of that shit, instead of because of it. I'm not sure if cocaine was the worst drug... or fame.

I got a lot better at showing off than at showing up. That's part of what happened to me. Instead of taking my gift seriously and adding some discipline to it and really celebrating being a writer, all of a sudden, I'm doing "The Gong Show." And I have to take some responsibility for that. That's part of the process. And the loss is a permanent loss, unless I use it. And that's why I talk about it at times like this. Although I haven't really shut up and let you ask me anything.

PCC:

[Laughs] Now that you are back on stage and singing the classic material, is there a sense of rediscovery for you, as well as for the audience?

WILLIAMS:

It's wonderful. And it is a discovery for me. And it's interesting to see what people still connect with. Frankly, I don't feel compelled to sing "Evergreen" all the way through. And yet I feel such a connection to like "The Rainbow Connection" or some of the songs from the Muppet movies. "Rainy Days and Mondays," I feel the weight of the song again. And I feel the weight of what I originally wrote with a new affection. But I also can see what the songs mean to other people. It's really sweet to have somebody come up to me and say "You and Me Against The World' was their dad's favorite song and they played it at the funeral or something. It's pretty special.

PCC:

I would think your songs in particular would play special roles in people's lives, weddings and those sorts of events.

WILLIAMS:

Oh, it's the best part of being a songwriter. And it's interesting, because it's a multi-generational thing. And there's a cut-off point. Somebody will be saying, "Oh, my God, this amazing writer!" And there'll be a kid standing next to him with a sort of glazed look in their eyes like, "What are you talking about?" And then they seem to come around, when they hear about the stuff from "The Muppets" or "The Rainbow Connection."

Or they will totally surprise me and I'll go to some place like The Loser's Lounge, in New York, they did a tribute, or something here in L.A., where I'm amazed at the 20, 21-year-old kids that know every song from "Phantom of the Paradise" or "Bugsy Malone." Or really oblique songs that I wrote that I didn't think that anybody remembered, something from "Boy in the Plastic Bubble." So it's a roll of the dice. Sometimes they know; sometimes they don't. The culture reinvents itself. So how we handle this gracefully is, I think, kind of the measure of who were are as artists these days.

PCC:

Do you think we got away from the song at some point? The singer-songwriter movement was huge in the 70s, then at some point, it seemed to be more about the production or hype than the song itself.

WILLIAMS:

My observations about that period would be tainted by the fact that I was having a large amount of out-of-body experiences [laughs]. I survived one of the longer chemistry experiments of the 20th century. I wanted to be Robert Mitchum, you know.

I was writing songs for The Carpenters and, when I really look at The Carpenters right now, I feel, "My God, they were alternative!" "In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida" was the number one album and they're doing "We've Only Just Begun" and "Close to You." [Laughs] Like, how brave of them! They were so brave. I don't think I ever really appreciated that.

But, although I was writing that kind of music, that kind of throwback stuff, I was running around with hair down to my ass and round, black glasses and the beginnings of a kind of glazed look. I wanted to be Robert Mitchum.

PCC:

Was that a problem for you, dealing with people's perceptions and those contrasting with what you wanted your image to be?

WILLIAMS:

Oh, I don't know if it was a problem or not, because, more and more, I wasn't there [laughs]. The time and the chemicals... The Game Show channel has been showing the old "Hollywood Squares" lately. And I was friends with Peter Marshall. We played golf together. Peter said, "You know, they're showing a bunch of your shows this week, Pauly."

So, of course, the ego responded and I turned it on and looked at them with my wife standing next to me. And what I was really expecting was,"Now you're going to see it -- we're talking Oscar Wilde; we're talking Oscar Levant -- major wit here." And they got to my first question and it was just that cocaine-jawed, glassy-eyed... I think the question was, "If somebody's under five-four, are they more likely to be a genius or not?" And my hilarious answer was something like, "Well" -- and I was almost impossible to understand -- [slurs] "I know they're better lovers." At which point, I kind of threw a kiss to the camera. And it was the kind of time travel that stops your heart, where you go, "Oh, my God! Was I like that all the time?" It wasn't funny. It wasn't cute. It was sad. And I just wasn't there.

I immediately called Peter and I said, "Peter, was I like that all the time?" He said, "No, of course not. We wouldn't have invited you back." But it was good for me to see that. You know what I'm saying, Paul? It's not easy to look at, but it's good to see, because it just makes me want to hit my knees with gratitude that what I'm experiencing today is real and I'm feeling it and I'm there.

PCC:

When you began writing again, did it all just fall into place or was it a painstaking process?

WILLIAMS:

The first song I wrote, the first day back, I wrote with a guy named Jon Vezner. And he knows that I tell this story. I hit my knees and prayed before I went to his house. I went into the bathroom at the hotel and said, "God, we're doing to write songs today and if you're in the mood, I hope you'll show up." And I was scared. I was really scared. I went over to his house and he's this really tall, Germanic-looking, thin man from Minnesota with a full black beard. And he just looked like he hadn't smiled since 1947. I thought, "F-ck, this is going to be a swell experience."

And I realized I was really scared and I asked him if I could use his bathroom. I wanted to go pray some more. And I went into his bathroom and I saw the Serenity Prayer on the wall. And it's the prayer -- "God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; the courage to change the things I can; and the wisdom to know the difference." An important prayer to us in recovery. I went running back out and I said, "Are you...?" He said, "Yeah." I said, "I am, too!" He said, "Yeah, I know." I was like, "Mommy! Pick me up and love me!" [Laughs] I felt safe.

And I realized that was the beginning for me, to sit down and just be honest with somebody. The great thing about writing that I'm finally experiencing is just the joy of sitting down with somebody you don't know, trusting them enough to have bad ideas in front of them and hearing their ideas and letting it roll. We wrote a song that day called "You're Gone." It was recorded three years later by a group called "Diamond Rio" and was a number two record [1998]. It took three years to get cut.

So this must have been six years ago, when I went to Nashville for the first time. But basically, we both sat down and talked about how we both came to get sober and the fact that there was somebody in our lives who had that kind of effect on us, daring enough to reflect the truth. They wouldn't be around us while we killed ourselves. So the chorus of the song is, "The good news is I'm better, for the time we spend together. The bad news is you're gone."

It's been a real interesting experience writing again. I've had more fun. I'm writing with people a third my age sometimes. The time other people spend in garage bands is usually before their career really gets started. I'm experiencing it now and enjoying it. And at this point, it's all a gift. I begin to sound a little like Pollyanna, Dr. Panglossian, in my enthusiasm for it. But that's because I really love it. I love my life today.

PCC:

So the experiences have colored the songwriting in some ways?

WILLIAMS:

What they've done, I use the expression, "My windshield gets dirty on the inside." And with my windshield clean on the inside, I'm allowed to really experience what's going on, really see what's going on, really experience the talents of the people around me. So I can truly collaborate, instead of gliding through the room [laughs], sort of dazed, speaking to a higher fount of poetic bullshit that's flowing out of me. I can really experience collaborating today. And I'm really loving it.

George Furth, who wrote "Merrily We Roll Along" and "Company" [with Stephen Sondheim] and whatever, George and I are doing a musical right now. And the key character in the musical is somebody who has rejected what they've done as, using my old line of "co-dependent anthems" and rejecting that part of themselves that's thinking that it's a Hallmark card wing to their personality that they have no respect for.

By the end of the play, they come to find out that, as, I forget the name of the guy who wrote the book "Air Guitar" ["Air Guitar: Essays on Art and Democracy" by Dave Hickey] , says, "We were writing about the most high and holy of all human emotions -- the ability to love one another." And it's pretty valuable and pretty sweet. It's worthy of our time. We should be proud of it.

PCC:

I'm surprised nobody has ever adapted "Phantom of the Paradise" as a theatrical musical.

WILLIAMS:

We've talked about doing "Phantom" a couple of times on stage. We did it with "Bugsy Malone" as a movie first and then we did it on the West End of London and it's become pretty much of a staple, an annuity for children's theatre and amateur theatre. Alan Parker [the writer-director] won't allow a Broadway production of it to be done. So there's been talk about doing it [Phantom] for a while. Brian [De Palma, the writer and director of "Phantom of the Paradise"] and I actually worked for a while on a version and then he went off and started a movie and it sort of fell by the wayside. But there's actual talk about doing it again. So we'll see what happens.

PCC:

You'll be doing a concert in San Francisco on a bill with Kris Kristofferson.

WILLIAMS:

Kris and I -- Kris Kristofferson recorded one of my songs with Rita [Coolidge], years ago. He did a song called "I Never Had It So Good," I wrote with Roger Nichols. And I've known Kris through the years. I haven't seen him, haven't spoken to him since right after "Star is Born." It's going to be interesting to share a stage with him, because everybody asks me, "Weren't you nervous about writing a song for Streisand." I said, "Of course, but I mean, excuse me, what really intimidated me, what really terrified me was the idea of sitting down and playing songs for Kris that his character was supposed to have written. I mean, "cleanest dirty shirt"? Give me a break. "Freedom's just another word for nothin' left to lose."? Excuse me.

PCC:

Have you done a show with him before?

WILLIAMS:

We've never shared a stage. When we were doing the promotional tours, stuff for "A Star is Born," we did like "The Tonight Show," maybe "The Merv Griffin Show." But he's just a brilliant guy. I'm looking forward to seeing him again.

PCC:

How much time are you spending on the road now?

WILLIAMS:

Not much. But in the last five weeks, I've made five trips across country. I had a show up in Detroit, came back here, went to Kentucky and Nashville, came back here and went back east for my daughter's graduation and then flew down to Pennsylvania for a concert, back here, went to New York for the Songwriter Hall of Fame induction, which I hosted for Bravo. Then I went to Mobile, Alabama for their drug and alcohol council down there. So in the last two months, I've flow across country five, six times.

Off to Washington Tuesday for the Association of Recovery School to speak before some sort of a Senate committee or something about starting this association. I'm involved with a school in Nashville called Community High School that's a private school where the entire student body is sober. And they're allowed to do 12-step meetings on the premises. And it's great, because these kids are coming out of school and they're staying sober. Other kids are coming out of rehab and going back to public schools and they're all getting high again. So this makes a huge difference.

PCC:

When was the last time you played San Francisco?

WILLIAMS:

Oh, God. I don't know. Have I ever been to San Francisco? I'll give you the alcoholic answer -- Maybe. I don't know. The last time must have been the Fairmont Hotel, I suppose, in the 80s, sometimes in the great dark days [laughs].

PCC:

And you have two kids?

WILLIAMS:

My daughter is going to be 18 in October. My son will be 21 the 28th of this month. He's an actor, just starting his career, Cole Williams.

PCC:

Acting, does it play an important part in your life at this point?

WILLIAMS:

Well, I love to do it. My wife always jokes that I could cure cancer and I'd be remembered for "Smokey and the Bandit" and writing "The Love Boat" theme [laughs]. When I was working as a drug counselor, I remember walking into a guy's room, when he was just fresh out of coming out of detox, bringing him down off of drugs. I said, "Hi, I'm Paul, I'm your counselor." He went, "No, you're not. You're Little Enos!" [Laughs] So I'll carry that to be deathbed. But I love to act once in while. If the phone rings, I'm shameless. I usually go and do it.

PCC:

And it sounds like you're actively involved in a number of programs to help others.

WILLIAMS:

Well, it's a huge part of my life now. There are several of us who have survived, who have a small amount of celebrity left [laughs], so it is a way to give back. And supposedly it's all about love and service. The thing is, if I stand up and I talk about my addiction, and I can say, "I'm Paul Williams..." They introduce me as an Oscar-winning, Grammy-winning, blah-blah-blah. And when I stand up and say, "I'm an alcoholic," maybe it does a little bit to reduce the stigma.

I mean, nobody's done more than probably Betty Ford for that. And I've had a nice relationship with them, and a few of the other ones, Hazelden. For a while I was on the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence board of directors. They're always looking for someone to come and tell their story over bad chicken at lunch.

PCC:

With all the awards, all the accomplishments, do you have other goals that you're burning to still achieve?

WILLIAMS:

I'd like to be a better father. I'd actually like to be a better conversationalist. I've turned to absolute strangers at parties and gone, "I have no social skills." [Laughs] I mean, it's one thing to jump on the phone and just start kind of blah-blah-blah, letting it all roll out and kind of try to talk about the things that I think are important here. You know? And it's another thing to sit down next to a stranger at a dinner table, when I literally think I have no social skills. I don't know what the hell to talk to this person about. It's a process. God's not done with me yet. We'll figure it out.

But I think I'd like to continue to write songs and watch my kids discover who they are in this world... I'd also like to break 100 on the golf course.

PCC:

Is that a realistic goal for you?

WILLIAMS:

Oh, it's a realistic goal. But it requires rigorous honesty [laughs]. And rigorous honesty in my life has kept me at about 104, 108. There's something in between my ears -- I should never, ever, ever add up my score on the front nine, because if I add up my score on the front nine and it's looking like I'm going to break 100, the back nine looks like a war zone.

PCC:

So this part of your life, does it seem like a whole new existence?

WILLIAMS:

Yeah, it feels like a second life. I joke about it, but in a lot of ways, I feel like Lazarus, that I've had, in a sense, two lives. So it's a gift. It's all a gift, Paul.

PCC:

You mentioned that your wife joked that no matter what else you did, you would be remembered for "Love Boat" and Little Enos. What would you actually most like to be remembered for?

WILLIAMS:

Oh, God... You know what? I don't even think like that [laughs]. The one thing that I've talked about, that's probably an unusual request, is that I want three dates on my headstone. I want my birthdate, I want the day that I got sober, and the day I die, because all three of those dates are important in my life.

What would I like to be remembered for? You know what, by the time I die, I'll be able to answer the question. No, it's an honor to be remembered. And I'd like for the songs to hopefully continue to be meaningful to people. And maybe we'll add some more before I get to the box.

For more on this artist, visit www.paulwilliamsofficial.com.

|