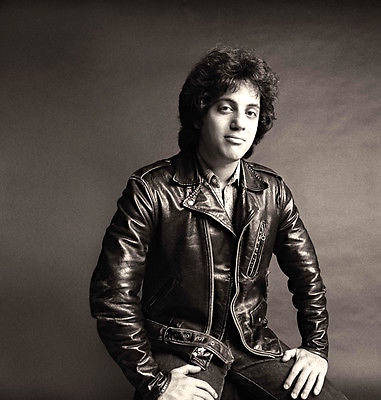

BILLY JOEL: KEYS TO THE KINGDOM

PCC's Vintage Interview with the Iconic Singer/Songwriter/Pianist

By Paul Freeman [1993 Interview]

He's a piano man who went to extremes and discovered his river of dreams.

Billy Joel began performing in the 60s and became one of the most important pop artists of the 70s and 80s. The extraordinary singer-songwriter's remarkable list of hits includes "Piano Man," "It's Still Rock and Roll to Me," "Tell Her About It," "We Didn't Start The Fire," "Only The Good Die Young, "Uptown Girl" and "Just The Way You Are."

We had the opportunity to talk with Joel, one of the best-selling artists of all time, while he was immersed in his 1993 "River of Dreams" tour. His most personal record and his last pop studio album to date, "River of Dreams" debuted at number one. Since then, Joel has released live recordings, as well as an album of classical piano compositions.

Twenty-five years later, fans are still clamoring to hear the hits. The Rock and Roll Hall of Famer, heading out on brief performing excursions, continues to dazzle audiences with his dynamic and moving music. In addition, Joel began a monthly residency at Madison Square Garden in 2014. At that venue, he has played over 100 shows, to more than a million people.

POP CULTURE CLASSICS:

You've in the midst of another major tour. Does it get grueling at some point?

BILLY JOEL:

It's grueling right now [laughs] and we're out for three months. But you know, I usually do tours that last about a year anyway.

PCC:

Is there a key to surviving that kind of schedule?

JOEL:

Well... is there a key to surviving? That's a good question. I guess, from time to time, you have to do silly things. Crazy things. Just to remain sane. Your sanity is more in danger of being lost, more than the physical. Although, here I am, I'm 44, and it is more difficult.

I can relate to Nolan Ryan. He knows a lot. He still had enough physical wherewithal to pitch, but he understands that there's an edge to the envelope. And he's going to walk away from the game before he can't play the game well anymore, because he loves the game too much. And that's how I feel.

PCC:

So it's in the back of your mind, that this is a finite thing?

JOEL:

This is the last long tour I'm going to do. I'm not saying I won't perform anymore... or maybe even play at the same venues that I'm playing at, although I doubt that. But I know for a fact that this is the last marathon tour I ever do. I said that at the end of the last one [laughs] and this time I'm saying it at the beginning of this one.

PCC:

This time you mean it.

JOEL:

Yeah, I mean it. You know, everybody bitches and moans at the end of a tour, because they're so tired. But I realize that this is kind of the end of a chapter for me. And really, look, the only reason -- and I'm speaking as a man -- to get into rock 'n' roll, when I got into rock 'n' roll, was to meet girls. I mean, anybody who tells you any different is either gay and they do it to meet guys or they're women and they're doing it to meet boys... or they're lying. It was to meet girls. Now I've got my girl.

And going up there and jumping around and being a performer... I'm not compelled to do what I do because I need the adulation. I like the kick. I like music. I like making this big noise with other musicians. That's fun. But touring -- that gets old.

PCC:

So what are some of the crazy things you do to keep your sanity, in the midst of a tour? What's the escape?

JOEL:

It's nothing really that outrageous. I mean, in the old days, we used to wreck hotel rooms, throw TVs out the window, all that typical -- the British actually taught us how to do that. They were the masters at it. But it's tempered down somewhat.

What we do is, we descend into this sort of gibberish. It's kind of a word-speak. And it's very scatological and it's ridiculous and it's nonsensical. And nobody understands what we're talking about, except us. And we constantly keep ourselves in stitches, because we speak in codes. And it would appear to people that we're gibbering idiots. And what we're really doing is speaking to each other in our own language to reassure each other that, "I'm okay, you're okay. The rest of the world doesn't have a clue what's goin on here."

What else? What kind of silly things do we do? The younger guys drink a lot, which can be dangerous, if they doing it. The drug imbibing has dissipated a great deal, I think in general, in the music business. The big thing now is AA and golf. And we see a lot of that.

PCC:

Were those things real dangers for you? Or just a phase to go through?

JOEL:

I was no saint. But on the other hand, I don't think it ever became a problem for me and I was able to change my life. A lot of times it's just good to not see your old friends. That's sometimes a great way to survive. But yeah, sure, I had my crazy times. Absolutely.

PCC:

Now that you're kind of settled down, how do you keep the family side of things at a stable level during a lengthy tour like this?

JOEL:

Well, I try to have them come out on the road, if they can come out. We even found a tutor for my kid, because I don't want to miss, really, any of her childhood. I didn't have a father when I was a kid. I always swore that, when I had a child, I would be around. And then here I am, Willy Loman, you know, humping my piano around the world. I'd hate to go home and be "Uncle Daddy." So I want her to come out with me as much as possible. My daughter is seven.

You know, Christie is very knowledgable about traveling. A lot of her work is traveling, too. So she'll go to a lot of cities that she'll find either some places that she can get some work done in or places that she'd like to be.

PCC:

As you described, a rock scene in the old days was not something you'd necessarily want to bring a child into. At this point do you have to explain to her -- this isn't exactly what most people would call real life?

JOEL:

Well, you know, in a way, it's funny. Part of it is very much non-reality. But another part is very much -- this is my job. This is Daddy's work. Welcome to Daddy's job, which is funny, because, a friend of mine died, not too long ago, a few weeks ago, and I went back for the funeral and I met all the guys from high school, I used to hang out with, who would tell me, "You're crazy for being a musician. You're nuts. When are you going to grow up? When are you going to get a real job?" And I've still got the job and I'm doing real well at it. Most of these guys are out of work. It's very bizarre how things ended up. So in a way, this is a very legitimate job. It used to be you were an outlaw, if you went into music. But after 30 years, I think I got the job.

So she knows that a lot of it is show biz. She's no stranger to that. She understands certain aspects of show business. She's been confronted a horde of paparazzi, clicking away, when she was very, very young. It scared the hell out of her. She's used to it now. So she understands -- you're supposed to smile, not run away and scream or hide your head. She was scared of it at first, but now she understands that's part of the game.

On the other hand, if I was a kid and my parents wanted to take me out on the road with a bunch of crazy musicians, I would have dug that. I don't think there's anything really wrong with that. And because it's the last time we're really going to do it, why not?

PCC:

You talk about the outlaw thing, kids getting into bands in their teens or early twenties, that's one of the big draws. So in your 40s, does the whole perspective change?

JOEL:

I think it's become very, very legitimate now. In the 60s, to decide to become a musician, it was fairly risqué -- Wow, you're taking on this bohemian lifestyle. Now you can almost follow formulas. The footprints have been put there for people to follow.

Also, there's so many different formats. I didn't decide I was going to be a "singer-songwriter," Adult Contemporary or Classic Rock. I mean, I didn't make those decisions. Now you actually sit down and go, "Well, let's see... I think I'll be a rap artist." Or "I think I'll be a country-western artist" Or "I think I'll be a heavy metal guy." Or "I'll be an alternative musician." That's where the perspective has changed.

I think where this music used to unite everybody, now I think it divides us from each other. I think we're all very fractionalized and we're all very separated from each other, because there's a snobbery. People who like heavy metal will not listen to anything but heavy metal. People like grunge will only listen to grunge. People who just like the old, classic rock will only listen to the old, classic rock. It's stupid.

PCC:

Do you envision that changing at any point? Or do you think we're going continue sliding in that direction?

JOEL:

Well, it's pretty rigid right now. The formats seem to be really unyielding and they're very stiff. I was talking to somebody, they're considering the old free-form format that they used to have in the 60s and the early 70s. And that format was, you would hear Otis Redding and then next to Otis Redding, you would hear The Rolling Stones. And then next to the Stones, you'd hear Jimi Hendrix. Next to Jimi Hendrix, you'd hear Wilson Pickett. We didn't know that there was some kind of pigeonholing that had to be done with this music. We just liked all of it. And if that format is ever tried again, I would hope that it would catch on.

PCC:

Do you think part of what has worked for you, in terms of transcending so many trends, is that you draw from so many influences?

JOEL:

Well, I liked it all. Like I said, I'm a child of the 60s. And I never had any snobbery about one type of music or another. I liked R&B. And I liked Cream. And I liked The Beatles. And I liked the Stones. I liked everything. I liked it all. I liked classical music. I even liked some country-and-western music. I liked blues. I liked everything.

I don't know. Maybe it has to do with musicality. I don't know if it has anything to do with style at all, ultimately.

PCC:

Were your parents supportive of the pop music? Or would they have preferred you to stick with classical?

JOEL:

My dad was a classically trained pianist. He grew up in Germany. He was very, very much a classical snob, although he began to like jazz, just before he and my mom split up. I know he liked some jazz. My mother liked classical music, but she also liked Broadway musicals. And she liked The Beatles. She liked some of the records I was playing. So she was pretty eclectic herself. I was really never discouraged from going into music at all. I was lucky that way. Nobody sat on my head and said, "You can't do that."

PCC:

Was your father a concert pianist?

JOEL:

He wasn't a concert pianist. He was a classically trained pianist. He would play piano purely for his own enjoyment. He actually worked for General Electric. And boy, did he hate that job.

PCC:

Was that a lesson in it itself -- being stuck in a dull job, when you'd rather be doing something creative?

JOEL:

Yeah, I always thought, jeez, if you're that good a piano player, why don't you do that? I never understood why he did this job that he hated. And I think maybe there was a lesson there. I realized early on in life that your job is a lot of your life -- Why not do a job that you love to do? I knew pretty early on what I was going to do. PCC:

PCC:

How old were you when your parents split?

JOEL:

I was about eight.

PCC:

Was your father in a concentration camp at one time during the war?

JOEL:

No, he wasn't in a concentration camp. I read that somewhere... but he was detained. He lived in Germany. He lived in Nuremberg. But the concentration camps became concentration camps, I think, later in the 30s, when the war started. Before that, there were a lot people who were detained, who were rounded up. They were put to work. But they didn't start killing people until the war. Although, I still don't think we know the whole story about that. But I know he was detained for a time. And then they left Germany. This was during the 30s. They got out. He doesn't talk about it. He doesn't want to talk about it. And he won't talk about it.

PCC:

The fact that there were these things he wouldn't talk about, did that color your world at all, at an early age?

JOEL:

Well, I knew that there were some terrible things that happened. It should have made me a lot more wary of people, I guess [chuckles].

PCC:

The story about Yitzhak Perlman, was that true?

JOEL:

Well, he actually met my father. The way it came down was, he had played on the record. And my father doesn't like pop music at all. He doesn't like rock 'n' roll. He thinks it's all trash. And then he had found that Yitzhak Perlman had played on one of my records. And he said to me, "Well, I guess you must be good at you do." The only time... It was sort of a backhanded compliment -- I guess you must be good. It had to be qualified though.

PCC:

Was your mother more openly proud of your success?

JOEL:

Oh, she digs it. She thinks it's great.

PCC:

Was it really The Beatles on "The Ed Sullivan Show" that sparked the fire to perform?

JOEL:

I don't think that sparked the interest in performing. I think what that did was to synthesize for me in one crystal clear moment what it was I was going to do. Because I'd always loved music. I knew I wanted to be in music. I didn't know what I was going to do. I didn't want to be a concert pianist, because when you took piano lessons, that's what they tried to get you to be, is a concert pianist. And that was no fun at all, doing that.

PCC:

Because it was too rigid?

JOEL:

Because it was playing somebody else's music. And it just didn't seem like they had a whole lot of fun, these guys. I came from a whole different generation. I was an American kid. I wasn't that impressed with some of the earlier rock 'n' roll, except for the black artists. I didn't like the whole Frankie Avalon, Hollywood-manufactured, rock star factory. I thought that was crap.

And then I saw The Beatles. And they played their own instruments. And they wrote their own songs. And they wore their hair long. And they dressed in this kind of cool way. And they had this look in their eye. Like Lennon would look in the camera and basically what Lennon was saying with his eyes to the camera was, "F-ck you!" And I thought, "I know people like this." I said, "This is great! These are working-class guys. And they're writing their stuff and they're playing their instruments. That's what I'm gonna do."

PCC:

And did you study all the records by all the British bands -- not just The Beatles, but The Dave Clark Five and all the rest?

JOEL:

Oh, I was nuts for all that stuff. I was in a band during the British Invasion, the first wave. And we did all The Animals, The Kinks, The Stones, The Beatles, The Pretty Things. All those bands. They were great.

PCC:

So fantasizing at that age about what it was going to be like, being up there with all that adulation, did it end up being close to the reality? Or not really?

JOEL:

Well, I met girls. That was really important, was just meeting girls. And I was also able to make some money at it. And I started working when I was 14, in clubs. And I didn't graduate high school, because I was working late at night with bands. A lot of people think of me as the piano man, working at a piano bar. But I only did that for six months. Most of my teen years were spent playing in bands, rock 'n' roll bands.

PCC:

Did you ever regret what you might have missed in terms of school, both the educational and social scenes?

JOEL:

No, because I passed tests. I was pretty well self-educated. I didn't have a TV when I was growing up. I read a lot. And I found out more from reading books than I was going to find out in a public school. I knew I was bad at math. All right. And still, to this day, that's being proved [laughs]. I'm not good at numbers. But I developed a love for literature and history and geography and all that stuff.

But I knew I was going to be a musician. I wasn't going to go to Columbia University. I was going to go to Columbia Records.

PCC:

The whole thing about getting girls -- did that seem like it would have been a difficult prospect without the music?

JOEL:

Absolutely. You know, I was never a matinee idol type. There were always better-looking guys. There were always guys who were more smooth-talking or better talkers. The big football hero types. I was kind of shy. And I'd go to a party and the more aggressive guys would be meeting the girls and talking to the girls and dancing with the girls. And I would kind of wander off into another room. And if there was a piano in the house, I'd sit down and play the piano. I'd look up and there'd be a girl. I'd play a little more and look up. There'd be another girl. And I thought, "This is amazing! This is some powerful stuff here." Realizing that, that helped me make my decision. [Chuckles] Being in bands is a great way to meet girls.

PCC:

Through the years of performing, did you become extroverted offstage, as well? Or did you retain some amount of shyness?

JOEL:

I still think that the onstage thing is pretty much sort of like Tom Sawyer walking on the fence for Becky Thatcher. As well it should be. There's a great deal of flirtation, sexuality. Boys will be boys -- that kind of thing.

PCC:

So is it better when Christie is in the audience?

JOEL:

Well, of course, because there's the element of the show-off thing. But there's flirtation. And that's part of the show. That should be going on. But like I said, I've got my girl. And basically, this is what I do. It's my career. Before I ever walked into a recording studio, I was on a stage, playing. So really the essence of rock 'n roll -- or pop music, whatever you want to call it -- is performing. It's being on a stage and playing this stuff with other musicians. And you're making this big, loud noise.

PCC:

Is there a special significance to this tour, because of the nature of the new album?

JOEL:

The significance is what the audience has become. We started to see this on the last tour. I assumed -- and I was mistaken about this, I think back in the 80s -- that I had developed this audience, a particular age group, and that would be the end of that and I really wouldn't be growing into a younger audience. And on the last tour, we started to see a lot more younger people coming in. And on this tour, the audience has been about 50 percent 20-and-under. So I don't know what the hell's going on. But it really has changed the nature of the show, just because of who they are.

PCC:

How has it changed the nature of the show?

JOEL:

They make a lot more noise now. We've always had loud, vocal audiences. But now, because we have more young people, now it's even louder. It's analogous to the sex act. If you're making love to somebody and they're making a lot of noise, you're usually better. You perform better. But if they lay there like a lox, eventually you just throw in the towel. So what's happening is, the audience has been so loud and so vocal that we're going that extra mile, because we're more adrenalized, we're more charged up.

PCC:

Well, certainly this album cooks throughout. But can the young people relate to the lyrical themes?

JOEL:

Perhaps to some of them, for some of the songs. I think "River of Dreams" is basically a spiritual song. I think almost any age, one can feel spiritual. The lullaby, hey, we all know what that's about. Having the blues -- I remember having the blues as a teenager. Feeling betrayed -- I remember that feeling, too.

You know, maybe it has to do with, I'm talking about being my age. I'm 44. And it ain't bad. I used to be scared to death of being in my forties. I thought, "What am I going to do in my forties? My hair is going to fall out. I'll start selling insurance. And I'll begin to have impotence." But that hasn't happened. I've slowed down physically and my voice isn't what it used to be. That I've noticed. I can't sing as well as I used to.

PCC:

I don't think anyone else has noticed. You're hiding it well [laughs].

JOEL:

I think I'm past my prime as a singer. It's not that it's bad. It's just, I recognize that. Maybe there's some reassurance for people who are younger to know that there's a guy in his forties who's still kind of this crazy rock 'n' roll guy and is having a good time and is saying, "It's okay. It's not bad." Of course, I'm a rock star and I'm married to Christie Brinkley. So that tends to skew my perspective a little bit [laughs].

PCC:

So does it bother you, when some people look at your life and think it must be perfect -- you must have no problems and you have no right to complain about anything?

JOEL:

Yeah, right. I'm aware that there is some of that. But the people who actually believe that are probably the same people who believe what they read in the National Enquirer. What are you going to do about people like that?

PCC:

The new album seems to reflect a newfound faith or a renewal of faith. Is that something that you went through in your own life? Was it a searching process?

JOEL:

I suppose it was. There was kind of a journey there. This character, who was me at the time, started out very bitter, very angry... and betrayed... and having the blues. And I put off writing, because, who the hell was I to say I had the blues? Come on, Billy Joel, successful career, married to Christie Brinkley -- what's this guy got to bitch about?

But I did have the blues. And my wife encouraged me to write it. She goes, "Why don't you write what you feel?" And I always go back to the masters. I was listening to the Beethoven symphonies. And there were days when this guy was very, very down. And he expressed it so eloquently that we still recognize the same emotion that we have two hundred years later. So we're connected to this man, because of that. It was important that he did that.

So I said, "Okay, I am going to write what I feel." By writing about it, I was able to work through it. And there had been a great loss of faith, the loss of myself, my faith in myself, in my own judgment, in my own ability to play music. I came to the conclusion that there are some people who are no damn good. Like my mom used to say -- and I said "Oh, mom, cut it out" -- she said, "Watch out, because some people are no damn good."

I always assumed that, even in the most bad person, there was some element of redemption possible. And then I realized -- and I think it happens in your forties -- there are some people who are broken and they are beyond redemption. They're just no damn good. And this was shattering. I had based all my writing on the principle that everything could be okay and happy-to-lucky and naiveté and innocence and that humanity was a wonderful thing and we were all noble and blah-blah-blah. And then you find out that there are some people that are just no damn good and you go, "Well, what the hell can I write about? Maybe all the premises I based everything I wrote about prior to this were wrong."

So that was a great crisis of faith. And then there was a feeling of betrayal by people I have trusted. Then I lost faith in my own judgment. How could I have been so stupid? How could I have been so trusting? And I just had a great crisis of faith. And naively again, I went on this search for justice. And then I realized, there is no justice. There is only faith... in the things that you can believe in that sustain you. And those things are all around -- loved ones or children or old friends... or your own abilities. I found out I was able to write. I was able to compose, that I am a good musician, that I got the job.

There are things that are things all around us that are very strong elements, that sustain our faith, that we can believe, that we may not even see, because we're so close to them, that we take for granted, that perhaps we don't think are important. But they're there. And that's kind of what the journey was -- I had to reaffirm faith in something.

PCC:

But you're still staunchly atheistic at this point?

JOEL:

I'm probably more of an agnostic.

PCC:

Oh, really? That's a significant change, actually.

JOEL:

Yes, it is. I've shifted somewhat. I'm not as purely ideological in my beliefs as I used to be. I was very rigid. I went into this in a song, "Shades of Grey." I was immovable at one point. And now the edges are getting grey. I'm not so firm about things anymore. I'm opening to discussions about something that I disagree with. I'm willing to hear another point of view. I'm willing to consider. I'm not as dangerous as I used to be. And, in a way, that's good. That's part of acquiring wisdom, I believe.

PCC:

What about the wisdom you've acquired about the business? Has your whole perspective changed regarding the industry?

JOEL:

Well, the interesting thing is, from the first time I ever got involved in the music industry, I was under no illusions that we were doing business with the Girl Scouts. This is basically, you know, based on cannibalism and rape... and exploitation and manipulation. And I assumed that knowing that and having an understanding of that, I would be able to survive the pitfalls. However I trusted someone who I didn't think was of the music business. This was someone who I made the godfather of my child. And that was, I think, my mistake was. I just blindly trusted someone.

PCC:

Has that whole legal situation been resolved? Or is it still in the courts?

JOEL:

Some of it has been resolved. The initial lawsuit, which is about the ex-manager, is still in litigation.

PCC:

Is that a cloud hanging over your head? Or can you try to ignore it at this point?

JOEL:

Well, it doesn't obsess me. And it doesn't consume me. At one time, it hit me very hard emotionally, when it really happened, because I'm someone who has had a long career and I've sold a lot of records and I did a lot of touring and I did a lot of writing and I worked for a long time. And to be told that I was $30 million in the hole was a bit of a shock. So I got myself out of the hole. Don't let anybody shed any tears for me. I'm very sound financially. I worked to make up for it. Of course, I'm still trying to make up for 10 years of my life that were taken away. But hey, it's my fault. I'm not saying that they're going to get off scot free. I'm saying that it was my own naiveté and my own innocence and my own ignorance. PCC:

PCC:

Do you see any positive, in terms of stirring up a little extra anger or hunger that you can use creatively?

JOEL:

Well, I got an album out of it. And it's the first time I've actually done, I guess, what is an autobiographical album, from A to Z. It's pretty a confessional type of writing, which I'm not used to.

PCC:

Do you ever start censoring yourself and saying, "Do I really want to reveal this?"

JOEL:

Absolutely. As a matter of fact, I have a little counter in my head that keeps hearing the word "I." And every time the word "I" comes up, it's a little demerit. It's probably from my maternal grandfather. He was an Englishman, a very, very intelligent man, a devotee of Bertrand Russell. This guy would read logarithms at night, as if they were novels. This was a really brilliant man. He would be in the midst of holding court and pontificating or talking, and he would say to himself, "Oh, shut up." And just shut himself up. And I thought, "Wow, that's so cool. That's a cool thing. The guy is stopping himself from holding forth."

And maybe that's where that comes from. I don't know. But the confessional type of writing isn't normally what I do. I usually write more from a journalistic point of view, as an observer. Some of it's autobiographical, but never a whole album.

PCC:

Do you find that you tend to learn something about yourself and then put it into a song? Or the other way around -- you learn through the songwriting process?

JOEL:

This time, I found it very cathartic to have written this stuff. I feel better having done it. I felt like I had to give in to the blues before I could see the things that were positive. I had to give in to vent, to rage, some grief.

PCC:

The song "Lullabye (Goodnight, My Angel)," did your daughter inspire that? How did that one come together?

JOEL:

Well, I always have the music first. I write music first, because music is the language. Sound is the language. Actually, the way I write is sort of like how I hear music. When I'm driving in car, a song comes on the radio, I like the song, I usually hear the melody, the singer's voice, the rhythm and some production elements of the record. I hardly ever hear lyrics first.

And if I like the sound and the melody and the rhythm enough, then I try to take the time and trouble to figure out what the lyrics are. So that's how I write -- I write music first. And then sometimes the music sits there for a while, because I've got to figure out -- what's in this piece of music? What is the emotional message that it's sending? What is it making me feel? What should be said on top of this music?

And I'd had this piano piece. And one night, not too long after I'd written this piece, my daughter asked me, "What happens when you die?" It's a tough question. She was six years old. I think all parents have to confront this question, because the idea of mortality is terrifying, especially to a young child.

So I thought at first, "Well, should I give her the song-and-dance about the angels in heaven and all that? Or should I tell her what I really feel?" And then it occurred to me that this is a perfect way to explain this -- I'll do it as a lullaby. And I wrote my explanation of what I think happens on top of this piece of music. And I recorded it on a little tape and I played it for her. And she got it. And she actually took from it. She understood it. She grasped the idea of how we can survive through the work that we do, through the art that we leave behind. She liked that, because she's an artistic child anyway.

PCC:

Is that something you're very conscious of, while you're creating -- the possibility of immortality through the art?

JOEL:

Well, I believe that this music will have a life... I don't if mine will, but I know that music has the power to do that, to transcend mortality. My mother sang a lullaby to me and I sing a lullaby to my daughter and she sings it to her child -- that's the afterlife. In way, it's like the Indians do with their talking history. Music can do that. I mean, Mozart is alive as he ever was, as far as I'm concerned. This guy is vital and potent and just bursting with life.

PCC:

You've written songs that were inspired by Christie. Is it sometimes easier to express something profound to her in the context of a song than to just come out and say it?

JOEL:

Well, one of the most difficult things to write is really a good love song, without it being really hackneyed, without it being cliched. It's really difficult to do. And I'm always thinking about how to do it, because love is such a strong emotion. And it's so difficult to be eloquent about it or to say it in a new way or to say it in a way that's meaningful to somebody without them having heard it before. There's the challenge.

And I think it is a very good way to express love to someone musically, sure. But they're tough to do. It's really, really tough to do. I'm also aware that people may perceive, "Oh, it's Billy talking about Christie again. Who cares? I'm so sick of them. Of course he loves her -- she's a beautiful girl, why do we got to hear about it? Blah-blah-blah. Why does he got to rub our faces in it?" And you know, I think I might feel like that, if I was outside this relationship. I'm aware of that and I'm sensitive to it and I try not to write songs that go, [taunting, sing-songy voice] "I met Christie Brinkley. Ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha." [Laughs]

PCC:

Well, certainly you've managed to imbue your songs with a universal quality, no matter how personal their origins. Is that what you strive for?

JOEL:

I think it's just because I'm a human being, like everybody else. As a matter of fact, I've tried to spend more time now being a human being, rather than worrying about and fussing about a career. The personal life is really what feeds the artist's heart. That ultimately is more important, not the business things, not the political things, not nickel-and-dime things. It's being a human being. I think an artist is a better artist being more of a human, because he can express more humanity. He can feel more of what a human being feels.

PCC:

In a society that seems to be losing it's humanity -- the song "No Man's Land" talks about the bored kids with the vacant stares...

JOEL:

Well, it's the "Beavis and Butthead" thing.

PCC:

Exactly. How are you going to protect your daughter from falling into this syndrome that seems to be running rampant?

JOEL:

I don't know. I think all you can do is try to instill in them a sense of values and ethics and be as loving as you can. You can't protect children from the world. Ultimately they're going to go out into it. And I'll try to pass along the lessons I learned from the mistakes I made. Hopefully she'll learn from that. But she's gonna have to go out there and face it on her own, ultimately. Sooner or later, you sleep in your own place.

PCC:

So if you find her glued to MTV...

JOEL:

She doesn't watch MTV. She doesn't really like TV that much. She likes to listen to music and she likes to read books and she likes to draw. She's not a TV kid. There's a show here and there that she likes. She doesn't really go for MTV.

PCC:

The song "I Go to Extremes," is that still you, to some extent?

JOEL:

Oh, yeah. Sure it is. My ode to manic depression.

PCC:

How do you handle the extremes?

JOEL:

I try to really live as boring and mundane a personal life as I can. I think it was Flaubert who said that. An artist should try to live as bourgeois an everyday existence that he can, or order so that he may be completely insane for his art. Because I find, when I'm writing, I'm absolutely on another planet. I'm not a very pleasant person to be around. I don't even like myself. I'm so obsessed. I'm so absorbed. I'm so internalized. I'm very, very far away, when I'm writing. There's nobody as unhappy as me, when I'm writing.

But there's no one as smug and satisfied as when I have written. You know what I mean? [Laughs] One of those. So I think that's where the extremes come in. I think the balance comes from just, when I'm not on tour, when I'm not writing, I'm really just kind of a quiet, boring person. But that's okay.

See, I never understood why people had to go and bungee jump. I understand that people need to get a thrill. My job, essentially, is bungee-jumping. So when I'm not doing my job, believe me, I stay as far away from bungee-jumping as possible.

PCC:

I read that at 21, you had a problem with depression and checked yourself into a treatment center.

JOEL:

Well, I was suicidal. I actually tried do to myself in. I took pills.

PCC:

What took you past that point? Was it partly your work? Was it the therapy?

JOEL:

What got me past it was, I checked into an observation ward, because I was feeling suicidal again, after I had attempted it. And I said, "Look you gotta help me. I just don't want to live anymore." And they said, "Okay, you have to stay for three weeks and we'll observe you." And the door clanged shut. And they take away your clothes and you walk around in this gown. And they give you Thorazine.

And you are in this observation ward with people who have deep, deep psychological problems, people who are true manic-depressives, people who are schizophrenics, people who are homicidal maniacs, people with Napoleon complexes, people who are trying to kick heroin, people who were profoundly disturbed. And I realized, after a day, walking around, being with these people, that my problems were nothing and that I was basically just feeling too sorry for myself.

So I would go up to the nurses' station, knock on the window and say, "I'm really okay. So let me out, okay?" "Fine, Mr. Joel, here's your Thorazine." And I had to stay for three weeks. And it was one of the best things I ever did, because I realized that I could resolve whatever problems I was having, when I was really feeling bad. And it was a source of pride to me never to give in to feeling that bad. But it was a great lesson to have learned.

PCC:

So that cured you of the depression?

JOEL:

It cured me from giving in to feeling sorry for myself for more than about 30 seconds. You know, I realized, I love my work. Even when I feel a little bit blue, I can sit down and play the piano and make myself feel better. Or I can even express the blues in a very musical way. And now it's a blessing. So I have so many things that are good, to be grateful for, that I can't really get down about anything. PCC:

Putting yourself into that initial tailspin, was it career worries? Personal issues?

JOEL:

It was a combination of stuff. You know, turning 21 is a difficult age. You're going from being a child to being a man, very tough age. I had broken up with a girlfriend. And I was still crazy about her. Nothing was happening with me musically. I didn't have any money. And I thought I was just another wasted, musical hippie on the dungheap of history. And what was the point of me being this lumpen waste of flesh?

PCC:

And now, with all your success, do you contemplate your place in music history?

JOEL:

Well, the interesting thing is, okay, we had a big number one album again, but then I look at the charts and there's "Bat Out of Hell 2." So what does that say? [Laughs]. It makes one humble. And the funny thing is, no matter how good a show I'm gonna do in L.A., I'm gonna get a bad review in L.A. That's the way it works. So I don't really sit around and think about my place in history. It doesn't obsess me. I just do what I do, because this is what I do.

PCC:

Do you ever grapple with the irony -- all the awards, all acclaim and yet there have been some critics that just can't seem to get into it.

JOEL:

Well, there's some who can. And it's interesting -- and somebody pointed this out to me -- that most of the reviews are good. I'm the one who always points out the bad ones. I'm the one who makes the big noise -- "Did you see what he said?" So I stirred up a lot of this crap myself. I think there was bad review once in L.A. I think it was Ken Tucker or somebody. And I stood up and I said "F-ck you, Ken Tucker!" I never heard the end of it. You can't get into a pissing war with the press. Forget it. You're going to lose. But most of the reviews have been positive. The enemies I've made, I've made myself, because I overreacted.

You know what? Everybody's entitled to their own opinion. That's another conclusion I've come to. Vive la différence, for Chrissake. That doesn't necessarily mean they're right. Some people have their minds made up. It's okay, if my music doesn't move somebody, if they don't respond to it. But my theory is, music is something which is subjective. You have an emotional response to it... or you don't. And if you don't, that's okay. But it doesn't mean that the music isn't good. It just means that you don't like like it. And I think what happens with critics, to an extent is, if they don't like something, they feel it's their obligation to say it's no good, because they don't like it.

Somebody gave me a book, it's called "The Lexicon of Musical Invective." And basically it's critiques of all the great composers, going back to Bach. And some of this stuff is hysterical, tearing apart Mozart, saying he's a sham. And Beethoven is bombastic and has no talent whatsoever. It's hysterical stuff. It's been good for me to read from time to time [laughs].

So it's okay. It's really okay, because ultimately, I'm the one who decides whether my stuff is good or not. That's what's important.

PCC:

And does that become more difficult, as the acclaim increases?

JOEL:

Yes, my standards get higher as I get older. I don't just want to equal what I've done. I want to do better. It's always higher, more, faster, better. And I am a pretty strict editor, which is why now I find that I write more in dreams than I do consciously. I've been creating a lot of music during dreamtime, because the editor is a nice guy, the editor up there. He's a real easygoing guy. The conscious editor is a son of a bitch. He won't let me get away with anything. But when I'm sleeping, dreaming, there's no editing department. It just goes.

PCC:

Can you actually induce this in some way? Or it just happens?

JOEL:

It just happens. Actually, I realize I've always been dreaming this stuff. My writing process was always trying to pry open the subconscious filing cabinet to see what was in there. And now I realize that what other writers refer to as inspiration is really a dream that's reoccurred. There's that moment when you think -- "Gee, this is happening so easily. This is so good. It's so complete. Could I have heard this before?" And the answer is, "Yes, you dummy. You dreamt it and it's reoccurring to you now. You did create this in your subconscious mind."

PCC:

In terms of what you're going to create in the future, you mentioned that this is the of end of a chapter, with the last big tour. Your albums are such complete journeys unto themselves. Can you envision yourself writing something like a Broadway show or a movie score? Is that an ambition of yours?

JOEL:

Yeah, you know, I thought about it. I kind of toyed with the idea, but never got serious until Pete Townshend cornered me over in this Rock and Roll Hall of Fame thing in Cleveland. He says, "Billy, you've got to write a musical." And I'm thinking, "What an amazing world. Pete Townshend, the guitar-smashing boyhood hero of mine, of The Who, is telling me that I've got to write a Broadway musical." So if somebody like Pete Townshend is telling you something like that, you've got to think about it.

PCC:

This was following the success of "Tommy" on Broadway?

JOEL:

Yeah, "Tommy" was being a big hit. And he's serious about the theatre, the musical theatre, altogether. And he said, "You'd be perfect for it." I said, "Wow, geez, if Pete Townshend tells me that, maybe I ought to think about it." But that would be a long project. You're talking about maybe close to two years and a lot of rewriting. And also you turn over a lot of control to other people. There's other people singing the stuff, there's a director, there's a producer, there's choreographers, arrangers, orchestrators. And a Broadway show, look, there's a couple of critics, if they don't like the show, the show closes. I mean, God! If that was my life, I'd be out of business. At least I have radio to turn to and let people make up their own minds.

PCC:

Are you constantly going to be looking for new challenges in music?

JOEL:

Yeah. I want to do some other things. I find that writing, in song form, for me, being the artist, very stifling now, because I have limitations as a singer. I have limitations as a performer. I'd like to write for women. I'd like to write music for other artists, other singers. I'd like to write orchestral music without lyrics, symphonic music. I'd like to write maybe with somebody else, maybe let somebody else try writing the lyrics or work with an orchestrator. Or do a Broadway musical. Or a movie soundtrack. I mean, there's so many things to do in music.

You know, people send me movie scripts, asking me to act. And I send them back, "Well, no thanks. I'm not interested in acting." "You mean you don't want to be a movie star?" And I say, "Isn't music enough?" Why would I want to do anything else?

PCC:

Sounds like there are more musical possibilities open to you now that there when you started out.

JOEL:

Well, there are a lot of options. And I've grown. I've matured and I see a lot of other possibilities out there that I wasn't aware of before. I do think it's time to try different forms. I've been doing these things called master classes, where I'll go to a university or a music school and I'll take questions from an audience, people who are interested in composition or performing or piano playing or lyric writing or technical questions about the nature of the music business, business questions, career questions, questions actually I would have liked to have asked artists when I was starting out. And it turns into quite an entertaining evening. After an hour-and-a-half, two hours of illustrating songs on the piano -- there's some music to it. I may end up doing that as performance, rather than what I'm doing now.

PCC:

Just you and the piano?

JOEL:

Yeah, in front of a small group of people, maybe no more than 2,000 seats. Ultimately, I think that's another way to perform. Look, I've been around 30 years in this business. I'm 44. It's time to be a coach now. I've had my days in the sun, on the bright, green playing fields. And it's time to be a coach.

PCC:

Often athletes who call it a day and walk away, find it's more difficult than they thought to step out of the limelight. They really miss it.

JOEL:

Oh, I'll always miss the sport. I'll miss the game. But I don't think I'll ever really be out of being involved in the game. Writing and composing now is much more fulfilling than performing is.

For the latest news and tour dates, visit www.billyjoel.com.

|