BOBBY HART:

PSYCHEDELIC BUBBLE GUM AND LOFTY THOUGHTS TO CHEW ON

By Paul Freeman [April 2015 Interview]

Robert Luke Harshman is, without a doubt, one of the greatest songwriters in pop-rock history. “Who?,” you may ask. You know him better as Bobby Hart. And he helped shape the sound of 60s.

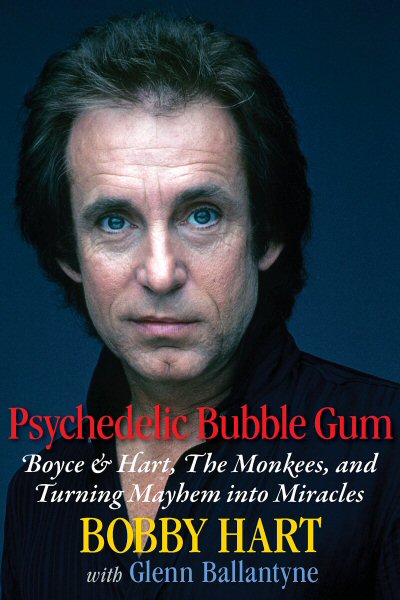

The Arizona native’s memoir, “Psychedelic Bubble Gum: Boyce & Hart, The Monkees, and Turning Mayhem into Miracles,” proves to be not only highly entertaining, but profoundly enlightening, as well. It takes the reader through marvelous musical adventures, detailing the writing, with his top-notch collaborators, of such timeless hits as “Hurts So Bad,” “Come A Little Bit Closer,” the theme to the daytime drama “Days of Our Lives” and the 1983 Oscar-nominated “Over You.”

The team of Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart wrote and produced the songs that launched The Monkees, including such classics as “Last Train To Clarksville,” “(I’m Not Your) Steppin’ Stone,” “She,” “Words,” “Valleri” and “I Wanna Be Free,” as well as the TV series’ theme song.

The songwriting duo evolved into a performing sensation themselves, making such memorable records as “Out and About,” “Alice Long” and “I Wonder What She’s Doing Tonight.” They wrote and sang the themes for the movies “The Ambushers” and “Where Angels Go, Trouble Follows.” In addition to musical performances on TV series like “The Hollywood Palace,” “Where The Action Is” and “Happening,” Boyce & Hart guested on the sitcoms “Bewitched,” “The Flying Nun” and “I Dream of Jeannie.” The duo’s brilliant 1969 album, “It’s All Happening On The Inside,” took them into more complex, pyschedelic-tinged textures.

But there is far more to Hart’s life story than platinum records and screen appearances. Like many great artists, Hart is a seeker. And the book details his spiritual quest, which led him into Eastern practices. It also touches on Hart’s involvement in the drive to elect Robert F. Kennedy and his determination to help the less fortunate, particularly children.

While Boyce & Hart were at their peaks as performers, they risked the wrath of the vindictive Richard Nixon by being at the forefront of the successful campaign to lower the voting age from 21 to 18. They wrote the anthem “L.U.V. (Let Us Vote),” which was sung at the rallies and even hit the charts.

In the book, Hart recalls many fascinating people he encountered, a diverse group that includes Coretta King, Jimi Hendrix, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Elizabeth Montgomery, Rosalind Russell, Del Shannon and Brian Hyland. He even engaged Hugh Hefner in a heated game of Monopoly.

Of course, the book also offers wonderful insights into the writing process for many of Hart’s unforgettable hits.

Bobby Hart talked with Pop Culture Classics about the memoir, his illustrious career, upcoming projects and his ongoing spiritual journey.

POP CULTURE CLASSICS:

You’ve led a truly a remarkable life. What was the emotional process like for you, reliving that life, the highs and the lows, as you wrote the book?

BOBBY HART:

You know, it was quite interesting. It was not quite what I expected. I played around with writing this on my own for several years. Finally, I hooked up with a co-writer. A partner has kind of been my M.O., throughout my life. I’ve always had much more fun working with a co-songwriter. And in this case, Glenn Ballantyne, who made the book so much better than it would have been on my own.

So the process was fun. But what was unexpected was seeing the patterns of my life. As you’re living it day by day, you don’t always notice things like that. But you step back and you look back 50 years and you see where you made mistakes and what the result was, and where you did things right… and how that worked out for you. So it became a real joy, actually. As we went along, we decided to make a point of trying to share some of the things that we both thought had contributed to my successes. So there’s some of that in there too, as you noticed.

PCC:

Yeah, I loved the interspersing of your “Stepping Stones for the Potholes of Life.” It was important to you to share that kind of acquired wisdom?

HART:

It became kind of a responsibility after a while. At first the book seemed like, “Well, this might be a good idea.” And then I felt, “Yeah, what am I writing this for? Just my own pleasure?” Of course, I hope others will enjoy it. But maybe they can do more than enjoy. Maybe they can find little tricks of the trade, some of the things that I learned that worked for me. Some of them might work for others, as well.

PCC:

That whole process of looking back, having that distance now, that did give you a different perspective? You were able to see things in a different light?

HART:

Yeah. It wasn’t like it was such a different light. It was just that the patterns became more apparent, as they would if you were looking down from an airplane, watching fields of planted vegetation. That’s a totally different thing to see the patterns in that way than if you were standing in the middle of the crop field or whatever and all you see are the little balls of cotton that you happen to be passing at that moment.

PCC:

The lifelong affinity for spirituality, did that save you from this very mercurial business? You didn’t fall prey to excesses that so many in the music world stumbled into.

HART:

Yeah, I don’t know what I would have done without it, really. Some of my contemporaries didn’t make it through those troubled waters. Some made it through, but had nightmares to face along the way. I didn’t have much of that. I had my times, things I’m not proud of, times where I made mistakes and all of that, but through it all, I could, in my darkest hours, turn back to the grounding that I was fortunate enough to have right from the beginning - my spiritual family.

PCC:

Even having a firm religious foundation right from the beginning, you chose to make a lifelong exploration to expand on all of that.

HART:

That’s true. I guess we all go through the steps of what works for us in the beginning. We may be looking for something deeper, something better, as we have our life experiences. Our lives get shaped by circumstances and the choices we make. And, in my case, I started looking for something… It was partly the cultural revolution of the 60s. The 50s, my young years, that was like a whole different world, where everything seemed sanitized. You didn’t think about the dark side. All the terrible things weren’t on the TV, because there was no TV, in the beginning [laughs]. And then when there was, there were still these nice gentlemen and ladies on the tube, not just all about the terrible atrocities we’re having around the world.

When the 60s hit, things became a little more real, it seemed. And, of course, it coincided with the escalation of the war in Vietnam and all of that. But also the love-ins, the be-ins and all of those things introduced me to Indian music, for instance, something that was totally foreign and yet seemed really wonderful when I first heard it at a love-in at Griffith Park. And just the concept of higher consciousness, the concept of changing your self, heightening your awareness - these were new concepts that kind of just came along with that movement in the 60s. So that helped, I think. That’s when I started looking around for something deeper than what I’d been taught at Sunday school.

PCC:

Those things that you found, do you think they affected your choices both on a conscious level and an unconscious level? So that even subconsciously, you’re being guided in the right direction?

HART:

You’re so right about that. When you start to try to make a connection with your higher power, whatever it is, if it’s your guru, if it’s God, if it’s Jesus, that connection with a higher power definitely opens up vistas of experience I believe that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. So I started with just reading my first stuff on spirituality that wasn’t totally Christian-related. It came about in my early, mid-twenties. And the first thing I was able to put to real use, that I can remember, was the concept of what your thoughts could create and the trick of visualization, vividly visualizing what it is that you want and how that triggers your brain in some way.

If you do it as a discipline, if you do it every day, your brain gets the idea, “Oh, I see, this is what I’m supposed to be leading toward so things open up.” I don’t know the actual dynamics of it, why, but I have a feeling that it has to do with getting rid of limitations that we all place on ourselves, because of wrong-thinking that we’ve acquired, something that somebody said along the way - and so you think, “Oh, I could never do that” or “I shouldn’t try to do this.” If you’re able to actually formulate a visual in your mind and see that every day vividly, the mind starts to get rid of all those limitations and say, “I guess I was wrong about that, [chuckles] maybe some of this stuff is possible.” That was one of the big ones that worked for me in the beginning. And it went on from there, I guess.

PCC:

All that self-exploration in the 60s and the political and social consciousness and conscience, are those things you think we need a lot more of these days, generally?

HART:

I think so. Everything’s cyclical, I think. So you had the very bland 50s - this is just my point of view. I’m not a student of this, but it’s what I experienced - and then the 60s were exploratory, as you just said. The 70s seemed to be back into self-indulgence. The drugs of choice went from ones that we were told would expand our minds to ones that would just make us feel good. Music was pretty much the same - the influx of disco and all of that. I’m not putting disco down. They had some great disco records in the day. There’s always good parts of anything, I suppose. But I think we’ve just built on the 70s since then.

And from what I see, there’s not much self-exploration going on, not from what I can see. It’s mostly just, “Let’s have a good time, while we can.” And it’s really looking for that in all the wrong places, because, unless you turn inside and realize your world is created from in there, it’s rough. You’ll just be chasing it your whole life. And it’s hard to find that way.

PCC:

And in terms of the political scene, it seemed like, with people like Bobby Kennedy, there was such a sense of true hope, which is missing these days. Do you feel that?

HART:

Absolutely. Well, we kind of had the hope with Obama. But the reality of it is, it’s tough out there. I don’t know why anybody would want the job [laughs]. But, because of our love for John Kennedy, Tommy and I really got involved with Robert Kennedy, when he decided to run for President. Campaigned for him, as you can see in the book. And that was a real disappointment, not only his assassination, but Martin Luther King. It was such a tumultuous time. And one that could have made people just give up. But you can’t do that. So you keep looking for the best of the future.

PCC:

A lot of people didn’t get over the disillusionment. You mention in the book that you have perseverance and optimism that have been keys throughout your life. Do you think those are things are partly something you are born with and partly qualities you were cultivating?

HART:

I do. And as I said at the beginning, looking back at the times when I didn’t practice it, those were the times I would get in trouble. The times when I said, “Well, this was a big disappointment, but let me just pick myself up and see how I can better the situation and go on to the next one,” those are times where things always worked out better. And I think part of it was innate. Of course, I always had choices at every juncture. So I was able to see a pattern early on, that I’m better off starting again and having a good attitude about something, rather than just hanging around and feeling sorry for myself.

PCC:

Early in your music career, during the down times, the lonely times - you talk in the book about living in a seedy New York hotel - did you ever come close to calling it quits?

HART:

Not really. That was in New York and, when I got to New York, that was like heaven for me, because, just the energy there, for one thing. I guess the number grouped in such a small area, there was just a vibe, which was real stimulating for me. And I knew that, at that time, Tin Pan Alley was the Promised Land for a struggling songwriter. So I just knew that was where I should be.

It was lonely, certainly. I didn’t know anybody. Tommy lived in a suburb and he’d go home to his girlfriend and I’d be in the city and just walking around, trying to wait till I was so sleepy I could just go to sleep. I’d get up the next morning feeling great again [laughs], without looking too much at the palatial digs of the Chesterfield Hotel on 49th Street. It was really a flophouse. But it was a warm place to sleep on cold nights. And that part I just overlooked and just appreciated that I was there and having opportunities I wouldn’t have had anywhere else.

PCC:

Looking at all the opportunities that popped up, the way they popped up - being in the right place, right time for “Hurts So Bad,” Don Kirshner taking the Monkees project away from you and Tommy and handing them to all these superstar producers, then not being pleased with any of the results and handing it back to you - it must have really seemed like fate was moving you in the direction of success.

HART:

[Laughs] Well, fate was moving around. It’s called the Fickle Finger of Fate. And it went back and forth. As you just mentioned, we thought we had the gig for almost a year, because we had been promised it by the producers of the television show, that we would be producing the records and the music for the show. But then Don Kirshner came out and said, “No, you don’t have the experience for it” and took it away. So we had a choice at that point, of just walking off and sulking for the rest of the year, or continuing to visualize. We really felt that was our project and we were going to find a way to do it. It turns out that we did. [Laughs]

Now, we didn’t sabotage any of the other people on purpose. But I think the attitude has something to do with it. And the stars line up… or whatever.

PCC:

But all these greats - Goffin & King, Snuff Garrett, Mickie Most - worked on the songs and then Kirshner was dissatisfied each time. You and Tommy were meant to forge The Monkees’ sound. It must have been destiny.

HART:

It’s true.

PCC:

As you’re moving into things like Psycho-Cybernetics, the visualization, the meditation, did all those sort of things seem like a fit right away? Did they come naturally? A lot of people struggle with those sorts of things, at least in the beginning.

HART:

Yeah, well, sometimes there were things that were over my head, some of the first spiritual books I read, like Gurdjieff. Alan Watts was more accessible, but it wasn’t really clicking. There were things I was learning and was inspired by, but also things that I was confused by. And when I ready “Psycho-Cybernetics” [by Maxwell Maltz], that made sense to me right away.

It required some discipline that I had started to work on, because I had started doing Transcendental Meditation. So I was used to getting up and disciplining myself to sit there for 15 to 20 minutes and just try to still my mind. So maybe that was the precursor that made it easier to accept, when “Psycho-Cybernetics” came into my life. That was a big eye-opener. And I really think it had a lot to do with being led to The Monkees project, within just a few months of practicing that visualization.

PCC:

And with all that brings, in terms of serenity and self-awareness, as well as the discipline, that must all benefit the actual songwriting process.

HART:

It does. I’ve always had, I guess, a certain innate amount of it. I didn't have a problem sitting in an empty room, staring down the yellow pad, trying to make a song out of it. I would sit there for however long it took. But that was different. That was the outer discipline. To get into stilling yourself, well, that’s a whole different discipline.

Until we sit and try to still your mind, we don’t have any idea what’s going on in that mind. It’s just chaos going on in there [laughs], just one thought after another. And some of them are so entertaining that you couldn’t possibly switch it off. So that’s the challenge, when you actually try to still your mind in meditation. And it’s an inner kind of discipline that’s much more difficult than getting up to go to work or writing a song.

PCC:

Did it seem surreal at some points, the incredible variety of people you encountered, from Coretta King to Jimi Hendrix to Zsa Zsa Gabor? Did it seem like a dream at times?

HART:

I never thought of it that way, although Paramahansa Yogananda, my guru, talks about life being a dream and at some point we will wake up and say, “Oh, yeah, that was the dream. This is the real reality,” just like we do, when we wake up here from a dream at night and say, “Oh, it seemed so real.” And, of course, it’s not. That was only a dream. This is the real reality. But he says there’s a reality beyond that, that we’ll get to sometime.

But at the time, as I was going through it, you come upon one of these experiences at a time. So when they said, “Oh, yeah, we want to hire you to play the main room in Las Vegas, but you’re not a big enough name to fill the room, you’re going to have to get this list and find somebody on there that you can partner with,” well, we loved Zsa Zsa from television, we thought she was funny, clever. So she was the first one we called. And, as you’re going through it, it doesn’t seem unbelievable - I’m actually talking to Zsa Zsa Gabor [laughs], learning a hat-and-cane number with Zsa Zsa Gabor. It’s just something that you’re doing, because that’s the next step.

PCC:

Do you think, long-term, you and Tommy would have been happy and comfortable acting in a sitcom and doing Vegas shows, if things hadn’t fallen apart, because of problems with your, shall we say, “colorful” manager?

HART:

I think it would have grown stale at a certain point. We all have to make a living and I think I would have been happy doing those things for a number of years more. I don’t know why it all came to an end like that so quickly, just at the height of our careers, where we did have a sitcom in development at Screen Gems. We did have a hit Vegas show and we had offers to come back to Vegas and also to take the show to Europe. We had our own record company and a successful track record as recording artists and producers. I could see that could have gone on… in some parallel world. But it didn’t go on in mine [laughs].

PCC:

With the R.F.K. campaign and the Coretta King evening and the lowering-the-voting-age movement, was it always important to you to use your success to do something in terms of giving back?

HART:

Yeah. I think that, once again, subconsciously, yes. But it seemed like these opportunities just came to us. I can’t ever claim that I was Joan Baez or one of those people that said, “Yes, I’m going to go down and march with Martin Luther King.” Or “I’m going to take a beating to stand up for justice.” We didn’t have that kind of commitment. We had a commitment to our careers, in the beginning. But then there would be opportunities that would open up. And we would say yes to them, because yes, we did want to see Robert Kennedy elected. Yes, we did want to see the voting age lowered for these kids that were drafted and being forced to fight in a war and they couldn’t vote for the politicians that were making these decisions.

I tell the story in the book about the girl that just would follow us around from city to city on our concert tours. She would show up backstage. And she was very pretty and very nice. And then we figured out, after a few weeks, she wanted us to join the Robert Kennedy campaign [laughs]. So they came after us. And thank God. And the same thing with the Let Us Vote campaign with Joey Bishop calling us up and saying, “Wanna be part of this?” We said, “Yes, we do.”

PCC:

It also must have been gratifying to you, over the years, having people tell you what your songs have meant to them, in their lives.

HART:

It’s always wonderful to hear those stories. I relate to it. From childhood on up, you hear a song, you know where you were first heard it. If the song was meaningful to you and you loved that song, you can just relive when you were hearing to it, relating to it, what things were like around you. It brings back those kinds of warm memories. So I totally accept it, when people make those kinds of comments to me, that whatever music has changed their lives. Somehow we were a part of that. I don’t know what part, but I just know that I’m very grateful that they feel that way and that they still relate to the music.

PCC:

On the first Monkees tour, playing with your group, The Candy Store Prophets, hearing that frenzied reaction, knowing that your songs were at the core of this mania, that must have been mind-blowing.

HART:

It was unexpected, I think by everybody. Of course, they had their television show, so they had this wonderful promotion tool. But the first shows that we went out on - and my band was backing The Monkees and opening the show - yeah, we’d seen it on television with The Beatles and others. But I didn’t think that it was going to be this unbelievably explosive. And there we were in the middle of it [laughs]. It was just a roller coaster ride. We just did the best we could to hold on.

PCC:

You mention in the book that, when Tommy saw the phenomenon of The Monkees in concert, he said you two should be up there on stage. Did you have the same sort of reaction?

HART:

No, I wasn’t thinking that. I was thinking, “Well, maybe The Candy Store Prophets will get a record deal at some point.” And Tommy had been mentioning it even before, that we should team up, because we both started this whole journey trying to be recording artists. We both had had a dozen or more un-hit singles [laughs], bomb singles. And so we had not much to show for it. We got sidetracked into songwriting.

So it made sense, when Tommy was kind of saying, “We should do this together. Look at the built-in audience we have. We’re in the fan magazines and so on, because of The Monkees.” And I resisted it. So once he saw that show at the Cow Palace, the first live Monkees show that he watched, he was pretty convincing by then. And he had our lawyer, Abe Somer, on board. And they convinced me this makes much more sense than trying to continue to be solo artists on your own.

PCC:

And when the duo’s success was happening and you were drawing tens of thousands at some of your shows and they were screaming for Boyce & Hart, did you just eagerly absorb that? Or was it a bit strange for you, as well?

HART:

No, that was wonderful. You don’t know it a little ahead of time, but when it happens, it’s just a form of love aimed at the stage. And you just get caught up into it and you want to please your audience. And I suppose everybody would love to have the feeling of being adored for a few minutes, sometime in their life [chuckles]. And most of us do… but on that scale, with thousands of kids, it’s pretty overwhelming when it first happens and you see that, whatever it is that’s making it happen, they’re just sending you a whole lot of good vibes, good feelings. And it’s automatic that you want to reciprocate.

PCC:

Have you seen the recent Micky-Michael-Peter Monkees concerts?

HART:

Yeah, I saw the Davy-Peter-Micky tours and then I did see the Micky and Peter and Michael tour. And they’re great. And the audiences are so great. The show Davy invited us to at the Greek Theatre, there were these two girls, probably, I would say, 11 or 12 years old, sitting right in front of us. And they were singing along with every song [laughs]. So at one point I just said, “How do you know these songs?” “Oh, we love The Monkees!” She didn’t explain, but somewhere they had found the music and related to it. And then, of course, there were the grandparents interspersed all around. So from the little ones to these older ones, it’s still a great show. I think Micky and Peter are off to Canada to do some concerts up there.

PCC:

Just the two of them?

HART:

Yeah, just the two of them. Michael has withdrawn again, doing his own things. But it’s still a good show.

PCC:

It must be so gratifying to see, 50 years later, that these songs still work so well.

HART:

Yeah, well, we went to see “Monkey Kingdom,” the Disney nature movie yesterday, my wife and I. And it opens up, [singing the opening of “Theme From The Monkees”] “Bu-dum… Here we come…” So those are nice surprises - to get a song in a movie or a commercial. You really don’t have any control over it. It’s somebody, the director or producer of the movie or the commercial - “Oh, this would be a great idea. Why don’t we use this song?” You just find out about it.

PCC:

And beyond The Monkees catalogue. It must be so satisfying to create a moving work like “Over You,” that worked so well in the film, “Tender Mercies.”

HART:

Yeah, that was with Austin Roberts, back in the early 80s. And it was fun. It was just another song that we wrote, that somebody recognized and wanted to nominate it for an Academy Award. And that was a fun evening. How many people get an opportunity to go to the Academy Awards and see all these stars sitting around you? It was fun to do.

PCC:

What are the elements of a good song that are always key, whether it’s in the 1920s, 60s or 2015?

HART:

Well, things are a little different today, but I think that always a good lyric, a catchy lyric and a catchy melody - that’s what pop music is all about. We always looked for instrumental riffs that would be identifiable, that would be easy to get with. And then also, vocal, melodic hooks, that are easy to sing along with. And I suppose it’s not too much different today.

PCC:

The concept you mention in the book - life as a symphony - can you elaborate on that a little bit?

HART:

[Laughs]

You know, there’s a concept that we all have a place in this universe. And there are those who think that it all happened, that we got created, by chance - some chemicals fell together or whatever and amoebas grew into whatever. Never made sense to me. It’s like the English scientist, I forget his name, [astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle] who said that thinking that creation could have happened that way would be like expecting a tornado to go into a junkyard and put all the pieces together to make a jet plane or something.

So my philosophy is - and a lot of people agree with me - that we all have a place in the universe that’s pretty much assigned, just like the planets. Pretty much they need to stay where they are. They do their job right where they are [laughs]. And the stars. And going down the other way, the cells that make up creation - the pieces need to do the job they were sent here to do.

So, if you carry that to the extreme of saying, “Well, I’m one of those pieces,” I think that we all need to pay our parts well in the symphony of life. And when we do, we can find that niche that works for us and that we really feel in the inner core of ourselves, “Yes, this is what I should be doing.” And we do it in the best possible way. I’m not saying we all have to be the conductors of the symphony or the star soloist. We can be the lowliest part of the orchestra, but if we mess up, if all you had to do was maybe do one cymbal crash at the important part of the symphony and you missed it, or you played it a little soon or a little late, it’s going to mess everybody up.

So we’re all inter-related. And we all can make a better world by playing our individual part better. Part of that playing is to create whatever peace we can in our own lives, not looking to a politician or a military person to create peace by being so powerful that nobody will challenge you. Peace is going to be created, and is created, individually. And the more people who are creating peace in their own lives, the way they treat their families and their friends and the people that they meet, that all adds up together to make the world a more peaceful place. That’s what I’m working on.

PCC:

As far as inner peace, in the book, you touch on a couple of the tragedies in your life. Does that whole spiritual essence, the knowledge that there’s so much more to existence than what we see, did that help you deal with those losses and get through them?

HART:

Well, of course a loss is always a loss. The death of a loved is always going to be painful. But it’s not as painful for the person who knows that there’s more, that life goes on after that. It’s not as painful. You don’t hang onto it for years and years and years. You wish the best for the person. And you know that they’re probably in a better place than we are here.

PCC:

Your wife MaryAnn, finding someone who fully understood and embraced all aspects of your life, has that given you a sense of completion?

HART:

Yeah, I wouldn’t call it completion, because I’m so far away from completion. But I’m working at it every day. And it makes it so much easier to have a spiritual partner on the same spiritual path, who is also working on her own life. And that made my life so much easier. I had my initiation into the highest form of yoga technique that my guru offers and, within a week, met MaryAnn. So it was like a real turning point for me. And it’s been great to have someone to share it with.

PCC:

With all you’ve accomplished, what do you view as being your greatest achievements?

HART:

You know, I think what I was just touching on - and I can’t call it an achievement - but just knowing that I’m trying to be a kinder person, trying to be a more aware and thoughtful human being. Just knowing that that’s what I’m working on, not that I’ve achieved it, but just knowing that I’m trying harder, that’s probably my greatest achievement. But really, it’s not an achievement at all - it’s a journey.

PCC:

In terms of sharing the wisdom, you’re a speaker on several subjects - collaboration, creativity and journey to spiritual fulfillment?

HART:

Yeah. Right now, we’re in the middle of promoting “Psychedelic Bubble Gum,” the book. And that’s really taking a lot of time. But when things calm down a little bit, my co-author of the book and I are going to go out do some speaking engagements and try to make ourselves available for some of that deeper, spiritual knowledge that we’ve picked up over the years and see if we can’t share it. I’m pretty sure there’s an audience out there, people who are looking for something a little more than what they’ve been taught before, what maybe they’re hearing in church every Sunday or whatever. And not to negate any of that. I would like to just share what’s working for me and see if it can help some others.

PCC:

As far as other projects on the horizon, what’s the status of “Uprising, The Musical”?

HART:

“Uprising” is a musical play that I wrote [about a native tribe whose land is being destroyed by a multinational logging operation] with Barry Richards and Klay Schroedel. We wrote 23 original songs. And Ron Friedman did the book. And Don Loze is going to produce. And it’s in the stage of development right now and has been for some time. But there’s always something positive on the horizon. It looks like it still might happen. And if you go to my website, bobbyhart.com and you buy a book, tell us the number of whatever you bought it on - Amazon, Barnes and Noble - you can download one of the songs from that show. It’s called “Not Today.” And I think people will enjoy it. It’s a different kind of a song for Bobby Hart. But I think it’s one of the best songs in the show and I think you’ll enjoy it.

PCC:

And the documentary about Boyce & Hart, “The Guys Who Wrote ‘Em,” is that nearing DVD release?

HART:

I think it’s going to find a home. It’s completed. Actually Rachel Lichtman [writer/producer/director] was in the studio yesterday, just doing some fine-tunes, because there’s going to be a screening at the Grammy Museum on the 20th of May. So it’s really finished, it just needs to find a home either on cable television or Netflix or something and then eventually, on DVD.

PCC:

At the beginning of the book, you talked about wanting to grow up to be a distinguished man, not only in the sense of standing out from the crowd, but also in terms of attaining a graciousness. So looking back now, can you say to yourself, “Yes, I’ve become the distinguished man I wanted to be”?

HART:

[Laughs]

You know, that’s still a work in progress, too. Yeah, I’ve distinguished myself from others by achieving some success, which is great and gratifying. But I’m still not as distinguished in the other sense of the word as I would hope to be. I’m still working on that one.

PCC:

You’ve accomplished a lot in that regard, as well. Any chance of a new Bobby Hart album.

HART:

Nothing on the horizon at this point. I never say no to anything. There’s always a possibility. We just see where life leads us.

PCC:

What do you most hope people will take away from the book?

HART:

There’s a ton of interesting stories in there, if you’re interested in that period and pop music in particular in that period. But what I hope they take away mainly is that I’m not just sharing the funny stories, but also the pattern of my life and some of the things I learned that helped to create that success, in my opinion, And it would work for anybody else who applied the same principles.

For the latest on this artist's projects, visit www.bobbyhart.com.

READ ON! BELOW YOU’LL FIND OUR EARLIER INTERVIEW WITH BOBBY HART. THERE’S MUCH MORE ABOUT HIS SONGWRITING PROCESS, THE MONKEES, and BOYCE & HART!

BOBBY HART: TITAN AMONG TUNESMITHS

By Paul Freeman [March 2011]

When you make a list of the greatest songwriters in the history of pop and rock, Bobby Hart should be near the top. Without Boyce & Hart, Monkees music wouldn’t have been nearly as irresistible.

Originally from Phoenix, Bobby Hart moved to Los Angeles to pursue his musical dreams. A gifted keyboardist and soulful singer, he was encouraged to develop his songwriting skills. He co-wrote the classic “Hurt So Bad,” a smash for Little Anthony & The Imperials and, later, for The Letterman and Linda Ronstadt.

Teamed with Tommy Boyce, Hart penned tons of hit tunes. Boyce & Hart first tasted chart success with the Chubby Checker disc “Lazy Elsie Molly.” They wrote the theme song for the soap “Days of Our Lives.” For Jay & The Americans, they came up with “Come A Little Bit Closer.”

It was Boyce & Hart who supplied the music for “The Monkees” pilot. The duo went on to write and produce many of the band’s best-loved tunes, including the TV show’s theme song, as well as “Last Train To Clarksville,” “She,” “Steppin’ Stone,” “Words,” “I Wanna Be Free” and “Valleri.”

They also wrote for movies, such as “The Ambushers” and “Murderer’s Row” (Matt Helm spy flicks starring Dean Martin), “Winter-A-Go-Go” and “Where Angels Go, Troubles Follow.”

Darlings of TV and the teen magazines, Boyce & Hart launched their own performing career. They rode the charts with such memorable numbers as “I Wonder What She’s Doing Tonight,” “Alice Long,” “Goodbye Baby” and “Out and About.” They recorded three terrific albums for A&M: “Test Patterns,” “I Wonder What She’s Doing Tonight” and “It’s All Happening On The Inside.”

After writing more than 300 songs, which sold over 42 million records, Boyce and Hart went their own ways in 1970. But they reunited to join Dolenz Jones Boyce & Hart, reprising the Monkees hits on tour and on record.

With other partners, Hart wrote music for such TV hits as “Scooby-Doo,” “Josie & The Pussycats” and “The Partridge Family.” He also created music for the cult film “Unholy Rollers.”

In the ‘80s, Hart recorded his first solo album. He also wrote and produced for New Edition and LaToya Jackson. In 1983, for co-writing the song “Over You,” featured in the Robert Duvall film “Tender Mercies,” Hart earned an Academy Award nomination.

For Pop Culture Classics, it was a pleasure to talk with Bobby Hart, who has played such a major role in rock history.

POP CULTURE CLASSICS:

So what’s occupying your energies these days?

BOBBY HART:

I’m writing my book these days, most of the time. And I do a lot of volunteer work at my church. Managing my music publishing company. I’ve got a project on the burner, but it’s a long-term project and a big-budget project, so it’s at the stage where people are looking for funding for it. It’s a musical play. So that’s not taking a lot of my time right now.

PCC:

Is this a musical using the songs you wrote with Tommy?

HART:

No, it’s a brand new musical with two other music writing partners. And a fourth partner who wrote the book for the play.

PCC:

And the book you’re writing, that’s an autobiography?

HART:

Yes.

PCC:

That should be a fascinating read.

HART:

Well, I’m having fun doing it.

PCC:

Is it an interesting process? Are you finding new perspectives on your life and career?

HART:

Yeah, a little bit. I’ve got somebody I’m doing it with. I’ve written it a couple different times in a couple different ways. And I was never happy with it. And this is an old friend of mine. I’ve known him since 1968. He owns a media company in Colorado. And he’s run political campaigns and done a lot of writing. He also knows marketing. So he’s a perfect partner for this, I think.

PCC:

But are you finding new insights as you go along?

HART:

It’s not so much insights into it, as much as it is insights into how to tell it. There are a lot of stories, vignettes that I’ve told over the years and I’m trying to get deeper into the feelings and the narrative of telling it as it’s happening.

There’s an interesting period that we’re up to now, which is ‘68 and ‘69, where we’re trying to work in a little political side to it. Although Tommy and I weren’t terribly political, we did campaign for Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign. And we were involved with the Southern Christian Leadership people, right after Martin Luther King had been shot. We met Mrs. King and worked for that.

Then we really got involved, in ‘69, in the campaign to lower the voting age to 18. We became the national spokesmen for the L.U.V., Let Us Vote campaign. So, in the book, we’re trying to sew that all together, add a little more political awareness into it, against the backdrop of Nixon, who was running. And, of course, we all found out four years later about all the dirty tricks he was doing.

PCC:

To release something with a social-political impact like ‘L.U.V.,’ was the record company behind that, as well.

HART:

Not so much, other than to let us do it. They let us put that record out.

PCC:

Which was, in itself, quite something for the time.

HART:

Yeah. It was Joey Bishop who got us involved in it. Joey liked us a lot, for some reason. He had us on his show about every four to six weeks, it seemed like. He had a nighttime talk show, opposite Johnny Carson. And he had been supporting this movement, which had been starting up north, at the University of the Pacific, in Stockton, California, a bunch of kids and college students. So he asked us, if we’d go up there for a L.U.V. rally and asked us if we’d like to write a theme song to along with it. And that’s how we got involved in it.

PCC:

It must have been gratifying to have a different kind of impact with your music.

HART:

Yeah. There was so much unrest at that time. Terrible things were happening. Riots all over. There were the black ghetto riots. There were the student protests on the campuses. There was the Democratic convention fiasco in Chicago. And the assassinations of both King and Kennedy within a few months. Just a real turbulent time.

PCC:

Having been drawn into the political scene through the Bobby Kennedy campaign, how did you handle that tragedy? Wasn’t it disillusioning?

HART:

It was disillusioning. And Tommy and I had both really been big fans of President Kennedy and that was the first time the wind was sucked out of us, out of the whole country, really. And then, to have that happen again, a few years later, and we’d been even more involved, it was disillusioning, but kind of spurred us on to thinking that, if we could get that younger demographic the right to vote, the 18, 19, 20-year-olds, we thought it would make a difference, because they were the ones behind the anti-war movement and the more progressive thinking. It didn’t turn out that way, though. They got the vote and still voted for Nixon for a second term.

PCC:

Did you get a sense generally during the ‘60s that the music was able to make significant changes in the social and political landscapes?

HART:

There were those, the real activists, Phil Ochs and Joan Baez and those people, who were out there. I’m sure that made a dent. It certainly raised awareness among the youth. I think the war was the big thing, though. It was affecting them directly. They were being drafted into a war they didn’t believe in. And then, when we started seeing the images on TV, about what was really going on over there, things started to turn.

PCC:

You mentioned being involved with your church. Is that where the musical roots are? The church music?

HART:

Somewhat, yeah. I was raised in church music. When I was a kid, we went to a Pentecostal church, which was pretty much like a rock ‘n’ roll church. It was great, great music. And we were there three or four times a week. We related to that Southern gospel, which was kind of a country version of gospel. And then I got exposed to black gospel in my teens and really loved the black gospel. That’s when R&B was starting to be accessible to the white audience, in the mid-’50s.

PCC:

Was your father involved in the church?

HART:

My dad was a part-time minister at one point. He was an X-ray technician his whole life. But he did have a church, for a time, that he pastored. But he never gave up his day job.

PCC:

Were your parents supportive of the pop music interest?

HART:

I left home right after high school. Came to Hollywood for disc jockey school and then got sidetracked into music right away. They knew what I wanted to do, what I was trying to do, but they weren’t watching first-person so much. And even after we were having hits, I don’t think they were that aware, for a while.

One weekend, I asked my Dad to come along. Tommy took his dad. We took them to this weekend of concerts that we were booked to do in Atlanta, because they were naming it Boyce & Hart Day in Atlanta and giving us the keys to the city and so on. So we thought it would be fun. They sent a camera crew along with us to document it.

So it was a real eye-opener for my Dad. From then on, he was my biggest fan. Up until then, I don’t think they knew, really, what I was doing.

PCC:

So the initial goal was actually to be a deejay?

HART:

Yeah. I knew I wanted to do something in music. I loved music. But I was quite introverted and shy in the early days. So I thought, behind the microphone in the radio station, no one will see me. I’ll be a deejay. That was my goal from, I’d say, maybe 10 or 12 years old. I had a radio station set up in my room. It became more sophisticated as time went on.

PCC:

And those were the days of the real personality type disc jockeys.

HART:

Yeah, definitely. And the number one station in Phoenix was country, so those guys really had a lot of personality. And I was kind of copying that, until rock ‘n’ roll came in. And then the Top 40 jocks came to the fore.

PCC:

So, outside of the gospel, what were some of the early musical influences?

HART:

Well, like I said, I was into country, because I didn’t really relate that much to pop. I’d listen to pop, but I didn’t really like the older, ‘40s-style singers like Jo Stafford. There was this TV show called ‘Your Hit Parade.’ They had a stable of singers that sang the Top 10 hits every week. And then, as rock ‘n’ roll started coming in they sounded more and more ridiculous trying to do the rock stuff. But those people, Snooky Lanson and Gisele MacKenzie, they didn’t have any soul for me. So I listened to country pretty much exclusively, until rock came in. Of course, country music was the first to play the rockabilly stuff, Gene Vincent and that stuff. And then I discovered the R&B side of rock, the black side of rock, and became more and more influenced by the black sounds.

PCC:

Had you studied piano formally, as a kid?

HART:

Yeah. I took violin lessons for three or four years and never really took to it and then I asked if I could switch to piano. But I had a classical teacher and I didn’t have the patience to learn sight-reading that much. Finally my teacher took pity on me and gave me a book of chords, which opened up a whole new world for me. I learned three chords and I could play any song on the radio. So then I really got interested. Later, in high school, I paid for my own lessons and probably learned more then than I did in my early years.

PCC:

At one point did you actually become conscious of the forms of songs, the structure of songwriting?

HART:

I guess, just listening so much, it was going in subconsciously. I guess in my teens, I don’t think I actually sat down and wrote a song, but I was aware. I can remember being aware, from walking to school, in maybe first or second grade, when I was maybe six or seven, thinking, in my mind, musical arrangements, like singing a melody and visualizing counterparts to go in between the melody. I don’t know where that came from, probably a previous life. But I was aware of those kinds of things real early on, arrangement ideas and so on.

PCC:

That must make you believe that you were destined to be in music.

HART:

Yeah, well I go to Self-Realization Fellowship, which is a church that was founded by an Indian yogi. And so we believe in reincarnation. It just explains a lot of why some people come with certain talents already formed, almost all ready to go at the time they get here.

PCC:

So, with this talent, at what point did you decide that, rather that becoming a disc jockey, you would go into performing.

HART:

Well, I started going to disc jockey school at night and I got a job. I hit Hollywood Boulevard, January 1st, 1958 and I got a job in a print shop, printing record labels and going to school at night. And I used to walk to work down Hollywood Boulevard and then down Vine. I would pass this little recording studio. It had a theatre style marquee. And it said up there, ‘Come in and see what your voice sounds like. $10.’

So I got intrigued by that, after a few weeks of passing it twice a day. I got my nerve up one Saturday, went in and laid down one piano track and put some background vocals on and made a little demo. And I was hooked from then on. And I would be there on Saturdays and spend all the money I’d made during the week. And I started writing then and demoing. One thing led to another. People would give me tips in there. One guy sent me over to see an artist manager and he signed me and I had a record right away. So I dropped out of disc jockey school probably within six months. I had found a new goal.

PCC:

When you began writing, were there difficult aspects? Or was it just fun?

HART:

It was just a fun thing. It wasn’t difficult at all. Still rockabilly was going on, Ricky Nelson and Elvis Presley. So I was pretty much doing that kind of style. And it was just great fun. I just really took to it and loved it. And like I said, I had a record deal within six months. A record came out maybe a year later, in ‘59. It wasn’t a hit, of course, but I got the experiences of going around and playing shows to promote it, went on tour a couple of times.

My job was running this Heidelberg printing press, so when I lost my first job, because I quit to go on tour, I realized I could go down to the Heidelberg plant and they would recommend me to another employer. So every time I’d go off for music and come back, I could get another job pretty quick.

PCC:

But when the first single didn’t instantly click, were you philosophical and just realized it was good experience you could build on? Or was there disappointment there?

HART:

Well, there was definitely disappointment. But I knew it was the beginning of what I thought would be a journey, one that would take a while. I would say maybe five or six years into it... I didn’t really have an success in the music business until ‘64. So I was probably starting to get a little more discouraged by that time. I’d had a lot of records out, a lot of tries, a lot of songs written and nothing to show for it, really.

PCC:

But you did have interest from other artists. Didn’t Tommy Sands record one of your songs, “Doctor Heartache”?

HART:

You’ve done your homework. That’s an obscure one. [Laughs]. That thing actually did make the charts for one or two weeks and then dropped off. But that would have been probably ‘63.

PCC:

That must have been a boost for your morale. Tommy Sands was well known at that time.

HART:

It was. And it was another boost, because that song, one of my high school buddies, going to school over here in Pasadena, he’d come over on the weekends, hang out with me and my wife, my first wife. And one weekend, he brought over his buddy, named Curtis Lee and he said, ‘This guy sings good. Maybe you can help him get a deal.’ So I introduced him to my manager and he recorded a couple things.

Anyway, that day, when I went to introduce him to my manager, was the day I met Tommy Boyce. And he was recording in a studio with my producer/manager. So Curtis and Tommy and I all met the same day. And, because I was married, I guess, Curtis and Tommy were the bachelors and they became pretty good friends and they were hanging out quite a bit. And they stopped over one night, must have been 1960, something like that, dropped over one night and said, ‘Have you been writing?’ So I pulled out, ‘Doctor Heartache’ and played it for them. I’d known them for a while by then and this was the first time that Tommy - he didn’t say too much, but I could see - he really liked the song a lot. And Curtis said, ‘This is great. Can I record this?’ And so Curtis was the first one to record the song. But I always felt that Tommy saw me in a new light after that and was willing to collaborate with me a little bit on songwriting. So that was the real breakthrough for me, was that Tommy Boyce and I began to do some writing together.

PCC:

And you and Tommy were in a car crash around that time?

HART:

Yeah, we went out to see Curtis in Long Beach. There was a rock ‘n’ roll show with a lot of acts on it. And that’s the night that Curtis got spotted by Stan Schulman, who was Ray Peterson’s manager. They were partners in Dunes Records. And he signed him that night, took Curtis back to New York to develop as an artist. A few months later, Curtis convinced him to bring Tommy back East.

But that night that we went out to see him, a guy came across the freeway, on the wrong side of the freeway, and hit us on the side. Luckily, everybody was okay.

PCC:

Was that enough to give you a sense of needing to live in the moment?

HART:

Absolutely. We were hit and then cops came, put up flares on the road and my wife, who was pregnant at the time, they told her to stay in the car. So we were talking to the cops and everything and then we see this other car barreling down the street, ignores the flares and hits the car for the second time, with my pregnant wife in it. the door came open and I saw her head actually bouncing on the pavement. That was a real slow-motion moment. But luckily, everything was fine. And our second son was fine, when he was born a few months later.

PCC:

Once you started writing with Tommy, was there instant chemistry? Did you feel that there was a special rapport?

HART:

Yeah, there was a rapport in general. He and I became good friends, and my wife Becky, my first wife. Once Curtis was in New York, then Tommy was over about every weekend. He was still living at home in Highland Park. He’d come into Hollywood and spend the weekends with us. And I’d help him with his songs, he’d help me with my songs. We didn’t take credit for each other’s help. But that was the beginning of our collaboration.

PCC:

So the formal collaborating, did that not begin until New York?

HART:

We did, after a while, write one or two songs that we started together, just said, ‘Lets write a song’ and sat down and did that. But then shortly after that was when he moved to New York. And I was still out here printing record labels. I had a local hit in L.A., so I was playing all the radio station-sponsored rock ‘n’ roll shows on the weekends.

PCC:

So what eventually took you to New York?

HART:

Well, after I was doing these shows on the weekends for a while, I met a guy at one of these shows, Barry Richards. And we decided, ‘Hey, let’s try to do what we’re doing on the weekends, only make money from it’ [Chuckles]. So we put a twist band together and started playing clubs. I finally quit my printing jobs. And we did that for a year-and-a-half or so and then, I think the real catalyst was, I split up with my wife. In the meantime, I had been signed by Don Costa, a New York producer, who was looking for talent. My friend Nino Temp had suggested me. So he started sending me fifty bucks a week... or maybe it was a month, I can’t remember. So I was signed as writer to Don Costa’s company as a songwriter and also he signed me in the same contract as a singer.

So, at one point, I just said, ‘You’ve had me signed now for a year. If I come back there, can we cut some records.’ He said ‘Yeah, come on back.’ So I went back there for that.

And Tommy, who was already back there, we hooked up again. And that was the real beginning of our writing partnership.

PCC:

So when did the Teddy Randazzo collaboration come in? Was that earlier?

HART:

No, soon after that. Teddy Randazzo was Don Costa’s partner in South Mountain Music. And Tommy and I would be in there in one of the cubicles, writing every day. And the general manager of South Mountain Music was also the personal manager of Teddy Randazzo. Teddy was kind of like a teen idol guy, but he was playing the Nevada circuit - Reno, Vegas, Tahoe - and other places around the world. I had seen him in Vegas and was really impressed with his band.

Anyway, I find myself back in New York, writing with Tommy at South Mountain Music and the general manager came in one day and said, ‘Teddy’s losing one of his background singers.’ It was kind of like a Joey Dee and the Starlighters kind of a thing. Teddy was behind the piano and then there were three male singers around him at a stand-up mic, doing oohs and aahs and rhythm steps. So he asked me if I’d like to go out and replace one of these guys, which I ended up doing.

PCC:

And then how did the writing of ‘Hurt So Bad’ actually unfold?

HART:

Don had signed Little Anthony and The Imperials to his label DCT Records. And he asked Teddy to arrange and produce. They’d done the first session, which yielded a couple of hits. The first record was, ‘I’m On The Outside (Looking In)’ and then they had a Top Tenner with ‘Goin’ Out Of My Head.’

We would be playing Vegas like 12 weeks on, 12 weeks off. So we were in Vegas, when Teddy called a band meeting between shows and said, ‘I’ve got to go this weekend, fly back to New York. I’ve got another session with Anthony, because ‘Goin’ Out of My Head’ is falling off the charts. He needs a new single. So let’s go upstairs. We need to write some songs for him.’

And so, it was just Teddy and his main writing partner throughout his career, Bobby Weinstein and I. I don’t think the band was invited, just the three background singers. Bobby Weinstein was one of them. I don’t why the third one begged off. But it ended up the three of us up in a banquet room, in a cold corner of a dimly lit room with a grand piano. And we wrote that between shows.

PCC:

Just trading off ideas, melodically and lyrically?

HART:

Yeah. Teddy always considered himself the composer, whenever he would write. And I found this out later, when I went to sign the songwriting agreements after the song was already on the charts, ‘Hurt So Bad.’ Teddy always took 50 percent of it, no matter how many people he was writing with, because he considered himself to be the composer and everybody else was the lyricist. [Chuckles] He did really create most of the melody that night. We were all throwing out lyric ideas. I think it was Bobby Weinstein’s title. Teddy started writing some melody to it. And I contributed probably the least of anyone. But I always felt then and through my whole career, it really didn’t matter - if you’re in the room and you’re contributing energy to a project, then you deserve a piece of it.

PCC:

It must have felt good, for years afterwards, hearing so many great covers of the song.

HART:

Yeah, it was pretty good to me. It made the Top 10 three times. Three different decades. Three different artists.

PCC:

And so, you and Tommy, did you decide to pair yourselves, or did the publishing company team you?

HART:

No, because we were friends out here, when I got to New York, we just started naturally writing together again. Tommy had been there now for a couple of years already, so he kind of knew his way around, publishers and everything. So there were opportunities galore back there. That was still the center of the music business, just before everything moved out West. There was a lot going on.

PCC:

Were you signed to a publishing company then? Or freelancing?

HART:

I was still signed to South Mountain. But then, when their money ran out, we started taking other opportunities. And that’s when I met Wes Farrell. Tommy and I were in 1650 Broadway, getting in an elevator and there was Wes. And Wes said, ‘Oh, you got anything for Chubby Checker? We’re taking the train down to Philly tomorrow.’ We said, ‘Well, we’ll go try to write something.’ So we went back to my little flophouse room and wrote something and that was our first chart record together. I guess it went Top 30 or something.

PCC:

You wrote it that night?

HART:

We wrote it that day and came back and played it for him and then went down to a little demo studio, made a demo of it and the next night, he took it to Philly. And that’s what Chubby picked out of the bunch. It was his next single.

PCC:

What was it like being part of that atmosphere, the Brill Building and 1650 Broadway?

HART:

It was electric. There was just so much energy. You’d constantly run into people, because the whole music scene was in those two buildings, mostly. You’d meet all kinds of talented, interesting, vibrant people. And you’d have those kinds of opportunities like the one I just described.

Then Wes and Tommy and I started to write. We wrote, I guess, a dozen songs or so together. And then we had our first Top Tenner, which was the Jay and the Americans record, which Wes, Tommy and I wrote.

PCC:

Did you have an inkling that the song was going to be so huge?

HART:

Well, that was obviously a fun lyric and a fun song to write. I remember we had a great time writing it. But when the record came out on a 45 and I played it, I thought, ‘I don’t know, I think the other side is probably going to be the A-side.’ Shows you what I know.

PCC:

Amongst all the other songwriting teams and solo songwriters in that scene, was there mainly camaraderie? Or competition?

HART:

I sensed the camaraderie side of it. I had really good experiences my whole career in the music business. I’ve heard horrors about other people, cutthroat business deals and all of that, but I never really experienced any of that and I somehow was protected from it.

In those days, for sure, the Tin Pan Alley scene, everybody was happy for everybody else. I remember running into Evie Sands on the street, having just heard her record, I think it was ‘Take Me For A Little While.’ It was just a great record. And I remember just being so happy for her. And others. That’s just an example. Neil Diamond was just getting started. And then all those great writing teams, the Nevins-Kirshner stable that had just been bought by Screen Gems, all those writers, everybody seemed to happy for everybody else.

PCC:

Once you’re hooked up with Screen Gems, does that create more pressure? Do you feel part of the hit factory syndrome?

HART:

No, because, we were then sent back to the West Coast. And all that was going on on the East Coast, all their main teams, Mann and Weil, Goffin and King, Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, all those people were back East.

When we got to California, we were basically it. They did have a couple of others. David Gates, I think, was signed and based out here. Maybe a couple others. But we would really get the best of the assignments, when we first came out, because there wasn’t much competition on the West Coast, especially on the movie and TV front. We were the guys who got to go out for the interviews pretty much.

PCC:

Writing for specific artists or specific situations, was that something you just took to naturally?

HART:

Yeah, because that’s how the business was and that’s what we saw our job to be. That’s just the way it worked. An artist is coming up to record in three weeks and so you’d think about, ‘What have they recorded?’ ‘What do they sound like?’ ‘What kind of songs do they do?’ ‘Who are they?’ ‘What do they want to say lyrically?’ And you try to craft something for them. And you do it quick. Especially on the TV we were asked to do. We’d often be given an assignment and we’d give them a finished demo two or three days later that they could lay into the TV show. We were like short order cooks.

PCC:

The ‘Days of Our Lives’ theme, did you approach that as just another assignment and try to figure out what would work for that setting?

HART:

Yeah. We got turned down twice. They told us - it was a husband-and-wife team, Ted and Betty Corday, had been very successful producers, back into the radio days, and they were coming out with the new one, ‘Days of Our Lives.’ They said they’d just seen ‘Fiddler on the Roof’ on Broadway and they’d loved this song called ‘Sunrise, Sunset.’ That was the feeling they wanted. So we wrote something that captured that. And they hated it. So we wrote another one. And they hated it.

So Tommy said, ‘Forget about it.’ We had no idea this show was going to be running for the next 50 years [Laughs]. We didn’t know what we had. So he said, ‘Let’s concentrate on writing songs, writing hits. They don’t know what they want, obviously. We gave them what they wanted and they didn’t like it.’

And we were at a little studio called El Dorado Studios, Sunset and Vine, doing a demo. And I guess we got the news there. Probably Lester Sill called to tell us they had turned down our second attempt. And I said, ‘Okay, I’ve got one more idea before we just walk away from it.’ There was a Hammond B-3 out there. That had been my instrument, basically, that I had grown up on, played at clubs and so on.

So I said, ‘Just roll the tape and let me just play some stuff that, in my head, sounds like the kind of music I used to hear on my mother’s soap operas on the radio when I was a kid.’ So that’s what we did. And that’s what’s been running for 50 years almost.

PCC:

Were there any assignments where you got blocked, that just made you feel like you were banging your head against the wall?

HART:

No, we usually could come up with something. The only time I can remember being blocked was when ABC TV sent a camera crew out to our house that we were sharing, in the Hollywood Hills. One of the magazine shows, I don’t even remember which one it was, wanted to do a piece on us. and they wanted us to just write a song in front of them [Laughs]. They set up these big lights and cameras and all this crew. And we sat down on the floor with this pad and, and we were just like, kind of, I don’t know.

First of all, they didn’t like the way our house was decorated. They said, ‘Don’t you have any knickknacks or anything that shows your personality?’ And they were bringing stuff in and redecorating our house [Laughs]. We were put off by the whole thing and then we sat there for a half an hour and just stared at each other. Or maybe it was longer, because we said we were going to take a walk and just get some fresh air, get reenergized and then come back in a few minutes and try again. And when we came back, they were gone [Laughs]. That’s the only time I remember actually being blocked.

PCC:

So being so prolific, did you find any tricks to stir up the creative juices? Or it just naturally flowed?

HART:

We just saw it as a job, I think. I’m sure there’s that element to it that was natural, that we had the ability, I suppose. But we weren’t thinking about that. We were just thinking about ‘This is our goal, this is our deadline. And what were Chubby Checker’s last three records? Okay, let’s do something like this.’

It was a good partnership. Tommy would strum something on the guitar and that would spark a line. It was just fun and easy with him.

PCC:

It seemed like you had a lot of diverse influences to draw from. You really hear that a lot in some of the later Boyce & Hart records, from classical to gospel to music hall, everything. Were you conscious of trying to bring in a lot of colors?

HART:

Yeah, we were. And, of course, we were always influenced by what else was going on, always. We always made it our business to listen to the radio all the time. We read the Top 100 charts in Billboard every week and we’d be familiar with every record on it and what the new, innovative sound was, the electric sitar or whatever it was that week, the catchy sound you hadn’t heard before. Always looking for that kind of stuff. Staying abreast of the changes, what the kids were buying that week. We saw that as our job.

The Beatles were a big influence, when they left the bubble gum stuff and started doing the George Martin-influenced arrangements. We were influenced by that. Whatever was good on the radio, basically, we were influenced by, I would say.

PCC:

When you first heard The Beatles, were you blown away, or was it just another pop band?

HART:

At first, it was just another band. It was like, they were playing the same songs I was playing in the clubs, cover songs, ‘Good Golly, Miss Molly’ and ‘Slowdown’ and that stuff. They were good, yeah. But there were tons of groups that sounded just like that over here. That was in the early days, before Capital started releasing them exclusively. There were Beatle records on I don’t know how many labels, probably a half a dozen or more, singles.

The first time I heard about them was when our friend Brian Hyland came back from England, told us about them. And he played us ‘Love Me Do’ and ‘Please Please Me’ on his guitar. He was real stoked, because he had seen all the reaction in England. This was before they came here and they caught on.

PCC:

With the British Invasion, even though bands like The Beatles, Stones and The Dave Clark Five were doing covers of American classics, they were also writing their own material? Were you concerned that there might be less demand for songs for hire?

HART:

We weren’t, because, for some reason, we were just ahead of the curve. At the tail end of Brill Building era, we moved out here just ahead of everybody else, before Goffin and King moved out here, Mann and Weil moved out here and everybody came to the West Coast. And so we moved on into those groups out here that were playing the Whisky, groups like The Leaves. We were watching The Doors. We didn’t write for The Doors, but we were being influenced by The Doors and other harder-edged groups like The Stones. And we were writing for some of those kinds of groups out here, Paul Revere and The Raiders and others. And kind of staying ahead of the curve.

We were already past the non-songwriter singers of the first half of the ‘60s. They were still primarily New York-based and they were the ones whose careers were, for the most part, ended by the British Invasion. We were already on into embracing the British Invasion and writing for The Animals and The Raiders and those kind of groups and trying to incorporate some of those psychedelic guitar sounds and so on into our productions.

PCC:

The Raiders, they actually had the first version of ‘Steppin Stone’?

HART:

Yeah, they recorded it before The Monkees, but they didn’t release it as a single.

PCC:

Big mistake. It must have been cool for you to hear, years later, so many punk bands covering that song.

HART:

Yeah, it was pretty wild to hear The Sex Pistols [Laughs]

PCC:

And then, when The Monkees project came up, was that, again, just another potential assignment? Or did you view that as a fabulous opportunity?

HART:

Well, both. It started as an assignment. We went over to meet with Bert Schneider, co-producer of the TV show, on the Columbia Pictures lot. And we were very stoked when we heard the idea, because we knew the power of television. We knew what happened when Rick Nelson sang his first song on television and it made him a star. We knew the combined power and we could just see the potential.

So Tommy, being the salesman of the two, really convinced Bert that we were his guys and knew what to do. At that time, he was just looking for three songs for the pilot show. And one of them was the theme song. So we convinced him and we were led to believe that we were going to be able to produce the records, not just for the TV show, but for the records, as well.

And so we worked on that. We demoed the songs and they accepted them, put them in the pilot. And then there was no enthusiasm from anybody else that we knew about. There were other writers, the New York writers, the staff, that were given the opportunity to write for the project once it was sold. But there was no interest in it. Maybe they didn’t know much about it before it was sold.

When it got sold was when Donnie Kirshner first became involved. We had worked on it for a year before he flew out and said, ‘You guys don’t have a track record as producers. You write hit songs, but I can’t let you produce.’ So he tried a whole bunch of other producing teams. And one by one, he didn’t like what he got back from from them. We’d sent him the theme for The Monkees we’d written. And he didn’t like their production of it. So we found ourselves, in August or so, without any releasable records. And finally we were able to talk Donnie into coming down and listening to - I was playing clubs in the night times - so I brought my band into the studio and rehearsed some arrangements on the songs. He came down, listened and gave us the feedback, ‘Sounds great. You can go ahead and produce.’

PCC:

What was the working relationship between you guys and Kirshner?

HART:

We didn’t have too much of a relationship. We would go to New York maybe once or twice a year. Stay in the company apartment and visit Donnie. We happened to be there when Time magazine was doing a piece on him, so we got our picture in Time with him. But we didn’t talk with him much. We would hear through Lester Sill, who was the head of West Coast Screen Gems music. But we didn’t really have much of a relationship until The Monkees and then he flew out and got quite involved.

PCC:

Is it true that you were considered for the cast, you and Tommy?

HART:

I don’t think we were seriously considered. They wanted us doing what we were doing, which was a full-time job, writing the songs and producing the records. Tommy was really thinking that we should be considered. But I don’t remember that it was serious. I remember going to auditions of other people and nobody was turning around and saying, ‘What about you guys?’

PCC:

Did you take notice of some of those people, like Stephen Stills, who auditioned?

HART:

Yeah, I didn’t know him. And I don’t think I watched that audition. But I know that he did and I know that he’s the one who suggested Peter Tork.

PCC:

And how was it decided which Monkees would sing which tunes?

HART:

The first recording date kind of set the stage. We had to get their leads on the songs for the pilot show. So that’s when we first met the guys. They showed up and they were just so high-spirited and competitive and trying to outdo each other with craziness that we couldn’t get a note out of them.

We hung out with them for a while and fooled around and then we said, ‘Okay, we’ve got to get this on. Take these lyrics. You know the song.’ And we rolled the tape and they weren’t singing. They were just fooling around. After two or three times, one time we looked up and there was like a dogpile on the floor, with a bunch of them just wrestling. And so after about an hour, we just dismissed the session. And that set the tone, because we resolved at that point, never to bring more than one at a time into the studio. That’s pretty much how we worked.

We would write a song with either Micky or Davy’s voice in mind and then, after their long day of shooting, we’d get them over to RCA Studios maybe at 10 at night. We’d teach them the song and get the lead vocal on it. The whole record would have been finished, except for the lead. So, usually in an hour or so, we could get them in and out.

PCC:

After getting to know them, how would you assess their individual musical strengths?

HART:

Instrumentally, musically, I’d say Nesmith was the real musician. He played good guitar. Peter was a musician, but his instruments were more folk-based, banjo and folk instruments. But he learned to play the bass pretty well. And the other two guys were actors, Davy and Micky, but had great voices. Micky still has one of the great pop voices, that holds up really well. And Davy, of course, sounded like The Beatles at that point. So he was helpful on certain kinds of material.

PCC:

Even knowing that the TV exposure was going to be a big boost for the music, it must have been exciting for everyone to see ‘Clarksville’ become such a huge hit before the show even aired.

HART:

Yeah, that was a real validation that we were doing something right. Even though, once the project was so successful, then Donnie, of course, was pulling in all of his writing talent and producing talent. He had everybody he knew vying for the next single.

We didn’t know that. We produced the first album and then the second album came out, we were surprised to see we only had two cuts on it. But that was the way it worked and it was a great second single, with the Neil Diamond song [‘I’m A Believer’].

PCC:

So you were able to take all that in stride, as just part of the business?

HART:

Well, we did take it in stride, because we could see how much we had made from the first single. And so were happy to have a couple songs on the second one. And he did let us continue to produce, even though we were aware that our productions would now be in competition with a number of other producers.

PCC:

What about when the boys themselves were added to that mix, when Mike pushed for them to control their own records?

HART:

Once they pulled the coup and got Donnie Kirshner fired and now said, ‘We’re going to produce all our own music,’ was perfect timing, because we’d gotten a lot of publicity in all the teen magazines, as the writers and producers, so we were fielding offers to be artists, at that point, which was what we both wanted to do. Tommy and I had both started in the business trying to be singers. So that was the perfect timing for that.

PCC:

That was so unusual at the time, for writers or producers to gain public recognition.

HART:

Well, because The Monkees were so big, they were monopolizing Tiger Beat, 16 and all those magazines. And so they were looking for anything they could find, that would give them a different twist on the story. So we were getting more and more photo sessions and space in the magazines, as the guys behind The Monkees.

PCC:

What was the experience like, touring with The Monkees, fronting your band, The Candy Store Prophets, being able to see first-hand the whole mania thing happening?

HART:

That played into it, as well. Nobody knew there was going to be that kind of response, that it was going to mirror Beatlemania so quickly and that audiences would grow so quickly. So that was a big thing.

And then, Tommy, after Candy Store Prophets and I had been out for a while, Tommy finally came to a show, in San Francisco, at the Cow Palace. And when he saw that, he just went bonkers. He came busting into my dressing room afterwards, he said, ‘Bobby, that should be you and me up there!’ [Laughs]

PCC:

It’s usually tough to be the opening act in that sort of situation, but the crowds must have accepted you, because you were part of the whole phenomenon.

HART:

I’m not sure, if they knew who we were or not. But they were polite. And it was just killing time till The Monkees came out. And then we backed them up when each of the four guys did a solo. We stayed out and did that.

PCC:

Were you involved in the tour when they briefly had Hendrix opening for them?

HART:

No, that was after.

PCC:

Were you there when Micky discovered Hendrix’s existence?

HART: