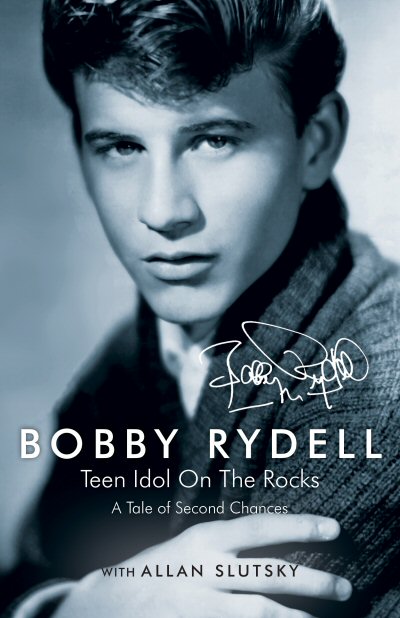

BOBBY RYDELL:

TEEN IDOL’S RISE, FALL AND INSPIRING RE-EMERGENCE

By Paul Freeman [April 2016 Interview]

Bobby Rydell, teen idol, was one of the most engaging stars of the early 60s - great voice, appealing personality, snappy patter, impeccable comic timing. With sparkling eyes and a beaming smile, he exuded a carefree confidence, an unaffected charm and warm sincerity.

But his life has had a tragic side, as well. And he tells his story with candor, poignancy and wit in his new autobiography, “Teen Idol On The Rocks: A Tale of Second Chances,” written with Allan Slutsky [Doctor Licks Publishing].

Rydell writes of his Italian family and growing up in Philadelphia. Encouraged by his father, he began performing as a precocious child. In his teens, he became a major star, recording such smashes as “Kissin’ Time,” “Swingin’ School,” “Sway,” “Wild One,” “Volare” and “Forget Him.” With Cameo labelmate Chubby Checker, he recorded the holiday perennial, “Jingle Bell Rock.” Rydell racked up 34 Top 40 hits, selling more than 25 million records.

At 19, Rydell, the wholesome heartthrob, was the youngest entertainer to headline at New York's famed Copacabana nightclub.

In addition to “American Bandstand,” appearances, Rydell was featured on many top variety shows of the 60s. He played Ann-Margret’s boyfriend in the film version of the musical comedy classic “Bye Bye Birdie.”

The public has never wanted to say bye-bye to Rydell. His hometown honored him by renaming the street where he was born “Bobby Rydell Boulevard.” In the nostalgic musical “Grease,” the teen characters attended “Rydell High.”

But in the book, Rydell also delves into the darker times, including his first wife Camille’s long, brave, but ultimately losing fight with cancer. Rydell battled the bottle. Alcoholism led to horrific health problems. On the brink of dying, he was saved by double organ transplants - liver and kidney. As he was recovering from that, he discovered he needed double heart bypass surgery to repair two severe blockages.

Through it all, such pals as Frankie Avalon, Fabian, James Darren and Ann-Margret d stuck by him. And his second wife, Linda, played a key role in helping Rydell to survive and thrive. Despite all of his health issues, Rydell made a rapid return to the stage, thrilling his loyal fans.

He performs his show regularly in Las Vegas and Atlantic City and continues to join fellow Philly faves Avalon and Fabian in the hugely successful “Golden Boys” tours.

Rydell’s new book, a wonderful, inspiring read, is now available from major outlets, including Amazon and Barnes and Noble. You can purchase an autographed copy, with personal inscription, from www.bobbyrydellbook.com

POP CULTURE CLASSICS:

As far as being able to take advantage of second chances, how much of that is luck and how much is inherently having a strong survivor mode?

BOBBY RYDELL:

Absolutely I felt it was a lot of luck. In fact, it was close to a miracle, because, on July the 8th, my wife and I were laying in bed and I told her, “You better get all our stuff together, get the lawyers, get everything arranged, because I ain’t gonna make it, hon.” And my wife was a nurse for 36 years and she was saying, “Oh, don’t be silly. Everything’s going to be fine.” But she knew deep down in her heart, that if I didn’t get the transplant, I was going to go. And the next day, we got a call from Jefferson Hospital to say, “Get on over here. We believe that there’s a liver available.” I went into Jefferson on July the 9th, it was something like 12:30 in the afternoon. And I was in the O.R. at 3:00 for 20-hour surgery, getting a new liver and a new kidney.

It kind of was a miracle, the way it happened, because, medically speaking, I’m O-Positive, which means I can give to anybody, but I can only take O-Positive blood. And my donor, Julie, who was from Reading, Pennsylvania, she was O-Positive and, unfortunately, she was hit by a car and immediately pronounced brain-dead, which allows the hospitals to donate the organs. And so, basically, that’s how it happened.

And after the surgery, I was talking to the doctors and this one doctor who was my kidney doctor, Dr. Ramirez, I said to him, “Doc, I didn’t know that I wasn’t the primary receiver.” And he said, “Bobby, you weren’t even the secondary.” And I said, “What do you mean by that?” He said, “There were 14 people in front of you, waiting for a liver.” Fourteen people turned down the partial liver. The primary recipient was a four-year-old black girl from Philadelphia named Assiah. And we split the liver. She got 25 percent. I got 75 percent of the liver. As you know, the liver is the only organ in the body that regenerates and grows. So she’s got a full liver now. I’ve got a full liver. And she’s now eight years old. I did a TV show with her here in Philadelphia and she looks absolutely fantastic. What can I say? We’re both very, very lucky people. It was a miracle the way everything happened.”

PCC:

And then, after surviving all of that, to find out you also needed heart surgery, that must have been devastating.

RYDELL:

Well, I was having a pain in my jaw and it was kind of going down my neck to the center of my chest, but I had no problem breathing and it wasn’t really anything I was worried about, to tell you the truth. But it kept happening and happening. My wife, being a nurse in cardiology for 36 years, said, “You better go over and get a stress test.” So yada-yada, I go over and take the stress test and we find that one artery is 85 percent blocked and the L.A.D., the Widowmaker, was 95 percent blocked. So I said to my cardiologist, Dr. Sokil, “You know, Doc, I feel fine.” This was on a Wednesday. And I said, “You know, tomorrow, I have to leave for Biloxi. I’m working a casino.” And he said, “You ain’t going to Biloxi. You’re checking in right now.” And I checked in and I got the double bypass on the following Monday. And… [chuckles] I’m kind of bionic right now - a new heart, a new liver, new kidney. And everything is fantastic. I feel fine. After the double-transplant, I was back at work six months later in Las Vegas.

PCC:

You must feel a sense of appreciation, having a chance to live these bonus years.

|

RYDELL:

You know what, I really got kind of a clear head. I was sick for the better part of two years, prior to getting the liver, with encephalopathy and ascites. Once I was fortunate enough to receive the liver and the kidney, as I was being wheeled in to the O.R., I was supposed to do a cruise in October and the surgery was in July, so as I was being wheeled into the O.R., I turned to my wife and said, “I’m going to make that cruise.” Because I figured one of two things were going to happen - I’m going to go into the O.R. and die on the table or I’m going to make it. And I’ve got a 50-50 shot. That’s the way I looked at it. And so far, so good. It’s going to be close to four years that I’ve had the new liver and new kidney. And three years with the heart. So what else can I say to you, Paul? I mean, I’m a very, very lucky guy and I’m able to do the thing that I’ve always done all my life and that’s singing and performing. I was able to get up on stage again.

PCC:

Writing the book, you go into the painful parts of your life. Was it difficult to be so revealing? Or was it healing, cathartic in some ways?

RYDELL:

You know what? Talking about alcoholism and drinking so much and actually becoming a drunk wasn’t hard to talk about. There were two things that were hard to talk about. One was the death of my first wife. We were married for 36 years and she had breast cancer. For nine years, she was clean and we thought, ‘Oh, she beat it. Everything’s going to be wonderful.’ And then in 2003, it came back and it came back with vengeance - the lymph nodes, the lung, the whole nine yards. And, basically, when she left me, it left a big void in my life. I was extremely depressed. And that’s what turned me to the liquor, to excess. That was hard to talk about.

The second part of the book that was hard to talk about was my Mom. But I think it’s very sincere, very honest. And I figured that, if I’m going to do this, I want to do this the right way, as hard as it may seem. I had to be truthful. I had to be very sincere. I would say those were the two things in the book that were the hardest to talk about - losing my wife and the part about my Mom.

PCC:

Through the difficult times, it must have helped to always have the music.

RYDELL:

Oh, my God, yes. It’s funny you should say that, because after my surgery, the double transplant, I guess I was home a couple of months and I’m just sitting, flipping through the TV and all of a sudden, I see the 40th anniversary of Tower of Power. And they start playing and they’re just kicking ass. They’re wonderful. My wife was out of the room. She comes in and I’m crying. And she says, “What the hell are you crying about?” I said, “They’re so wonderful. Look how great they are!” And they’ve become friends - the whole band, Tower of Power. And that really helped me on my way to recovery. I mean, everything was so great and wonderful that it made me feel fantastic. Even the crying was great. It was great for the body.

And, as far as they music is concerned, yeah, I’m so happy to still be able to sing, because, after the surgery, having tubes down your throat, I said, “Oh, holy Christ, what’s going to happen to my chops?” And a few months after the surgery, I got three guys together - piano, bass, drums - friends of mine, real good players. I said, “Can you come over to the house? I just want to see what the hell’s coming out of my chops.”

We just did tunes like “Shadow of My Smile,” “I’ve Got You Under My Skin,” and we did “Volare.” And I’m singing and it was hard making some of the notes. And I turned to the bass player - his name was Craig Thomas, who has played bass for me countless times - and I said, “Craig, be truthful, man. What does it sound like?” And he says, “I don’t know, man, sounds like Bobby Rydell to me, man.” [Laughs] And then six months after the surgery, I was back on stage in Las Vegas.

PCC:

In reading about your early days, it really sounds like you were a born performer.

RYDELL:

Well, like I say in the book, if I had any talent whatsoever, my Dad was the first one to see it. Seven, eight years old, he used to take me around to clubs and ask the club owners, “Can my son get up there? He does some imitations and sings some songs.” And when people started applauding and I’m only seven years old, I say, “Gee, all I have to do is this and they do that? What a wonderful feeling!”

Also, in the book, I was three years old, my Dad was overseas. And my mother’s writing, “The baby’s always singing. The baby’s always singing.” My father writes back and he says, “Who knows? Maybe one day we’ll have a star in our family.” And the reason I’m in the business today, it was my Dad. He had so much faith in me. I guess he saw talent in me at a very, very early age. And God bless him. If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t be in this business.

PCC:

Seeing Gene Krupa perform, that was an early inspiration for you?

RYDELL:

Oh, yeah. My Dad was a big band lover. And there was a theatre here in Philadelphia called the Earl Theatre. I was five years old and he took me along. It was an afternoon performance. And it was Benny Goodman. I didn’t know Benny Goodman. I didn’t know any of the big bands, back then - Dorsey, Tex Beneke, Artie Shaw - so we went to see him and all of a sudden, there’s this guy sitting behind the drums, didn’t know who the hell he was, but I said to my father, “I don’t know who that guy is, Daddy, but I want to be him!” And, of course, it turned out to be Gene Krupa. And at five or six years old, I started playing drums. And I still have a set, set up here in my music room. I still love to play.

PCC:

And in terms of the vocals, were you more influenced by the pop singers like Sinatra, rather than the rock ’n’ rollers like Elvis?

RYDELL:

Absolutely, yeah. I would venture to say that, around 10, 11 years old, I was listening to big bands, I was listening to jazz. I was listening to Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Dave Brubeck. And around that age, as well, I became a big fan of Sinatra. So what I do now on stage, of course I incorporate a lot of the hits, but then I do an awful lot from the American Songbook, the songs that I kind of grew up with, because I never really, even when I got a bit older, I never really listened to rock ’n’ roll all that much.

I was kind of like a jazzer and a big band type of guy. But the only way to make it at that particular time was to go in, record a record and rock ’n roll was big and then all of a sudden, you become a teenage idol. And if it wasn’t for that, of course, I wouldn’t be around here today. But deep down in my heart, my music lies with the American Songbook and jazz, big bands and stuff like that.

PCC:

So later on, to be getting praise from Sinatra himself, that must have been incredibly validating.

RYDELL:

Yeah, well, the story about that, I didn’t know that, and I became very friendly with Frank Jr., God rest his soul, because he passed away. We were supposed to be doing something together here in Atlantic City, in September. And I said to Frank Jr., “I just want to thank you, Frank, for all those things you said about me.” He said, “What are you talking about?” I said, “Well, you said that I was one of your favorite singers and out of all the young kids…” Frank Jr. says, “I didn’t say that.” I said, “Yeah, I read it.” He says, “No, it was my father.” [Laughs]

PCC:

And in retrospect, it must be great to know that it was this legend of jazz, Paul Whiteman, who gave you your stage name [Rydell was born Robert Ridarelli].

RYDELL:

Yeah, how about that? I guess Mr. Whiteman, Paul Whiteman, he wasn’t like a Tex Beneke, an Artie Shaw, a Dorsey, a Goodman. But he did one piece of music that was absolutely fantastic and that was “Rhapsody in Blue.” And he was a big band leader. He had a TV show, called “The Paul Whiteman TV Teen Club,” which gave young talent a chance to get a shot in the business. And I won on the show and I became a regular. And the piano player in Paul Whiteman’s band was a man by the name of Bernie Lowe. And I was 10 years old, when I did that show and then all of a sudden, I’m 17 years old and Bernie Lowe was my boss. He was the president of Cameo Records in Philadelphia.

PCC:

And then with “American Bandstand,” did Dick Clark take on a mentor sort of role with the young talent, offering big brotherly advice?

RYDELL:

Dick was always absolutely wonderful. He was a gentleman. He respected all of us guys, not only myself, but Avalon, Fabian, go on down the list, he really respected everybody. But coming from Philly, where the show was originally based, we’d always hear, “Well, of course he’s going to play your record.” No, no, no, no. Like they say, if it wasn’t in the grooves, it wouldn’t get played. I had three records for Cameo that Bernie Lowe took acetates, dubs, and Dick turned them all down. He said, “No, that’s not a hit record.”

And then, back in the summer of 1959, Bernie took him an acetate of my first hit record, “Kissin’ Time.” And when Dick played the record, he said, “That’s a hit!” And then, of course, you go on the Clark show, “American Bandstand,” from 3:30 to 5:00. It goes across the country, coast to coast. And Dick is playing the record. And he became my champion. I was extremely friendly with him. And he was a perfectionist. When he moved from Philly down to L.A., to do Dick Clark Productions, and did the anniversary of “American Bandstand,” he was a perfectionist in everything he did. He wanted to do everything right. If it wasn’t, he’d throw tantrums. He would really go crazy. But he got what he wanted and everything worked out well.

PCC:

What do you think it was about Philly in those days, that it became such a hotbed of pop music?

|

RYDELL:

Well, I consider myself very lucky to have been able to record for Cameo, which became Cameo-Parkway, because it did have its own sound. It was like Motown in that sense. When the needle dropped on a Motown record, you knew it was a Motown record. And the same thing, I would say for the sound of Cameo. When a needle dropped down on a record, you knew it was a Cameo record.

And we had a studio here in Philadelphia called Rec-O-Art, which became Sigma Sound. And lot of musicians, rock acts, went to Sigma. Earlier in my career, it was called Rec-O-Art and the guy who owned it, Emil Corson (a recording engineer), and the studio was so good, all he had to do was go in, put the lights on and turn the mics on. The studio just had a great, great sound and I think that’s why everybody wanted to record in Philly. And I don’t think they did all that much, when it became Sigma Sound. They wanted to keep that sound, that specific sound that was Philadelphia.

PCC:

And even though there were strong friendships there, was there also a sense of competition amongst the Philly teen idols - you, Frankie Avalon and Fabian?

RYDELL:

None whatsoever. You’ve got to realize, we were all born and raised in South Philadelphia, no more than three blocks away from each other. Fabian and I were born on 11th Street. And Frankie was born on 9th Street. I’ve known Frankie since I was 10 years old. He was playing trumpet and I sang and did impersonations. And we used to go around, veteran’s hospitals, USO shows, little dances, and perform for the people, again, at a very early age, as well.

And back in 1985, we put this show together called “The Golden Boys.” And that was Dick Fox, my manager’s idea to put three Italian kids who were teenage idols, to go back on the road again. And the show has been extremely successful. And I turned to Frankie, we had been on the road, doing 80, 90 one-nighters in a row, and I said to Frank, “How long do you think this is going to last?” “A year, two years tops, it’s going to be over.” And that was 1985. It’s 2016, we’re still doing it.

And the show is even better than it was when we started it. And Avalon says a great line, he says, “Look at the three of us. We were three guys in Philadelphia, hanging out on a street corner together. Here we are now, hanging out on stage together.” And that’s the way it is, because we just go out there and have a great time. We have a wonderful time. And people really, really enjoy it. It brings them back to that wonderful time, the mid to late-50s, early 60s.

PCC:

Back in the day, when the hits were coming, one after another, even if your manager was cautioning you about keeping your feet on the ground, did you think it was going to last forever?

RYDELL:

You know what? I was so young at the time, but I remember Bernie Lowe saying when “Kissin’ Time” became a hit for me, he said, “Okay, Bobby, you’ve got your first hit. Now the second one’s going to be even harder. And after the second one, the third one’s going to be much, much harder. And so on and so forth.”

So I never really knew. I would go into a studio. They had the material. I wasn’t a songwriter. I didn’t do lyrics. I didn’t do melodies. They wrote the lyrics and the melodies and I learned them and I went into the studio and recorded them. I didn’t know if they were gonna be hits. Sounded great to me. Everything that I recorded sounded really nice. I didn’t know if they were going to be hits, but I was lucky to have a good string of hits… something like 34.

PCC:

As far as staying grounded, was that partly because you decided to stay in Philly? Marrying your high school sweetheart? How were you able to manage that?

RYDELL:

Well, I was 15 and my first wife Camille was 14 and we kept company for 10 years and we finally got married in 1968. And she used to come and see me, prior to us getting married, and she was never introduced as my girlfriend. She was my cousin or a close friend of the family [his manager’s advice, to preserve the illusion of availability for Rydell’s female teen fans]. But she dealt with it. I don’t think she liked it that much, but she dealt with it, she accepted it.

PCC:

So what were the best and worst aspects of being a teen idol?

RYDELL:

The best, I guess it was the adoration of all of the fans, the screaming, the yelling, all of the fan mail, I mean it was absolutely fantastic. And I always use the line, I think other people have used it, as well - When we were teen idols and we had the pompadour and we wore the sweaters and then all of the girls would throw up keys and bras and pantyhose and now, in the twilight of my career, they throw up Depends [laughs]. So being a teen idol, that was a lot better [laughs].

PCC:

Did you feel pressured or constrained, having to maintain a wholesome image as a teen idol? Having to be a role model?

RYDELL:

No, I really didn’t, Paul, because, once again, Bernie Lowe said to me, after I’d had a couple of hits, he said, “I want you to remember this Bobby. You meet the same people going up the ladder as you do coming down. And if you happen to be a son of a bitch, when you’re up there, if you’re slipping down, they give you a little shot to get you down there a little faster.” That always stuck with me.

I never had that big-head attitude. I always considered myself as just the guy next door, the guy you can knock on the door and come in and talk and have a cup of coffee, sit and watch a ball game, football, baseball. And it’s still that way today. My fans will tell you that I have the time for everybody. If they need an autograph, I’ll take the time to sign autographs. If they want a picture, I have the time to take a picture. So, no, it never really affected me, that stardom. I always figured myself as a very level-headed guy.

PCC:

Having the opportunity to guest star on the TV shows of so many legends - Red Skelton, Jerry Lewis, Milton Berle, Jack Benny - what were those experiences like?

RYDELL:

Well, other than the TV shows, my first appearance in Las Vegas for two weeks, at the Sahara, was with George Burns. And then I had the wonderful opportunity of doing TV with Jack Benny and Red Skelton and Danny Thomas and Perry Como. And I’m still a puppy. I’m 21, 22 years old. And all I remember is that, when I left the stage, when Mr. Burns introduced me and we came out together, we did soft shoe with a derby and a cane, a little tap dance, and when I was done, I used to stand in the wings every night to watch him. I wanted to see how he delivered a line, how his timing was. And with all of those giants that I worked with, you could do nothing but learn. And that was a great experience for me at a very early age, to be around these wonderful talents.

PCC:

And “Bye Bye Birdie,” that must have been an incredible experience, as well.

RYDELL:

Well, yeah, sure. I went out and I screen-tested with Ann-Margret for George Sidney, who was the director. And he’d look into the camera. They wanted to see what kind of personality you have, how you come across on camera. Then Ann and I read lines from the script. We sang. She sang, “One Boy.” I sang “One Girl.” And Mr. Sidney was smiling. And we left.

And I’m home in Philadelphia. And Frankie Day, my manager calls me up and says, “Columbia just called and they want you for the part of Hugo Peabody.” Wow! What more can I ask? First of all, working with Ann-Margret was absolutely gorgeous. And to this day, we’re still really, really close friends. And then Dick Van Dyke and Janet Leigh and Maureen Stapleton. And it was a ball. It was really a hoot, man, because that was my first major motion picture. Not that I’ve done a hell of a lot of motion pictures, but if I had to do one motion picture, “Bye Bye Birdie” was fantastic and to this day, it’s a classic.

PCC:

And then you actually had a shot at the lead role in “The Graduate.”

RYDELL:

Yeah. There was a guy by the name of Lynn Stalmaster, who was a casting director. And he cast me for “Combat,” a TV show with Vic Morrow…

PCC:

Great show.

RYDELL:

Yeah, it was. And the show we did was really kind of crazy, because it was just Vic Morrow, myself, a truck and a German tank. It was just Vic and me. And Lynn Stalmaster cast me for that. And then he threw a script in front of me. He said, “Bobby, I want you to read this. Then I want you to come and read in front of me.” And the script was “The Graduate” and I read lines in front of Mr. Stalmaster. And he, in turn, went to Mike Nichols and said, “Bobby Rydell just gave me a hell of a reading.” And Mike Nichols was the director of “The Graduate.”

And, from what I understand, Mike Nichols kind of like sat back, thought and said, “Well, no, he’s not what I’m looking for.” And when Dustin Hoffman got the part [chuckles], he was kind of nerdy. And I wasn’t like that. I was the teenage idol, the one that everybody loved, the pretty guy and so on and so forth. And then, when I saw the movie, like I said, Hoffman was brand new, he was kind of nerdy. And that’s what Mike Nichols wanted. But at least I read for the part - you know?

PCC:

With the British Invasion taking over the pop charts, it must have been ironic to hear about that connection, that one of your singles, with its answering backing vocals, sparked the idea for The Beatles’ “She Loves You,” with its “yeah, yeah, yeahs.”

RYDELL:

Yeah, right. And, as you know, from reading the book, when I first met them, it was on a bus tour. I was on a bus with Helen Shapiro, a real fine female singer in the U.K. And there’s a car in front of us and she says, “There’s The Beatles.” I didn’t know what the hell they were talking about. This was 1963. They came on. They knew me, the four guys. And we shook hands. And from what I knew, they were a band that played nightclubs or cafes, they played dances, a wedding, you know? “Nice meeting you.” And they left and we went on our way and they went on their way.

I come home. It’s 1964 and I put on “Ed Sullivan” and there are The Beatles. I said, “Jesus, I met those guys!” And really, to this day, I could kick myself - how great a picture that would have been, the four of them, before they made it, and me, in the middle of the U.K. on a bus.

And then later, in his documentary, Paul said that, “We got ‘yeah, yeah, yeah’ from Bobby Rydell.” Well, that’s fantastic. And we sent to see Paul about a year ago. He was here in Philly at the Wachovia Center. We took pictures with him, kind of reflected back on when we met and all of that. He kind of remembered [laughs]. It was wonderful.

PCC:

In terms of sustaining the career after the teen idol peak had faded, did it help that you had, early on, been recording standards, as well as the teen material? Did that make it an easier transition to appealing to adult audiences?

RYDELL:

Yeah, absolutely. I just worked the Golden Nugget here in Atlantic City. We had a 17-piece orchestra - three trumpets, three ‘bones, five reeds, piano, bass, drums, rhythm guitar, full percussion, three girl singers, three voices. And, of course, when people come see a Bobby Rydell, a Frankie Avalon, whatever it may be, they want to hear the hits. So of course, we do a certain amount of hits, but the thing that people didn’t know, and when they see the show, they go, “Wow! We didn’t know he really could sing this type of material!” And I’m talking about doing tunes from the American Songbook, whatever they may be, could be Rodgers and Hart, Hammerstein, whatever.

And I’ve always loved that material. And other than the early years - rock ’n’ roll, being a teenage idol - this has sustained me through my career. I’m singin’ my ass off right now. I mean, my chops are really great. And I’m able to do not only my hits, but the material I really enjoy doing.

PCC:

What do you see as being the big differences between being a teen idol today and in the 60s?

RYDELL:

Hair. [Laughs] Had a lot of hair back then.

PCC:

You have a new film coming up?

RYDELL:

I did a cameo in Robert DeNiro’s new film, a film called “The Comedian.” And from what I understand, this is a pet project of Mr. DeNiro’s, that he had on the back burner, and he wanted to do, and he’s finally doing it. And the director, Taylor Hackford, I met him in the makeup room, prior to going on set. And he introduced himself to me. He said, “Bobby, Taylor Hackford.” I said, “My pleasure, Mr. Hackford.” He says, “I’m a big fan of yours.” Because he’s the one who asked for me to be in this picture, in this particular scene. It’s an autograph convention scene. And he wanted real celebrities to do this.

So I said, “Thank you ever so much, Mr. Hackford.” He says, “You know the scene, don’t you, Bobby?” I said, “Yeah, it’s an autograph convention. I’m sitting down at a desk. I’m signing pictures and people are coming up and DeNiro’s sitting to my right.” He said, “Yeah, that’s basically it. But once we get on set, I may have a couple of ideas.” Now, I didn’t know what the hell he was talking about. So we go on set and all of a sudden, I’ve got four or five lines with DeNiro, which is phenomenal [laughs].

PCC:

Looking back, what’s been the most rewarding aspect of the life in show business?

RYDELL:

[Pauses] You know what it is? I think it’s just the pleasure that I give to people, when they come and see me, to see everybody smiling in the audience, enjoying everything that I’m doing on stage. That’s the most important part. First of all, I’m so lucky to still be able to get up on stage and do what I’ve loved since I was three years old. And to make those people happy, I think is the most important thing in my life…. [Singing in the background] That’s my wife’s ringtone - “Volare” [laughs]. She has “Volare” and I have Dean Martin as my ringtone - “Ain’t That a Kick in the Head.”

For the latest news and concert dates, visit www.bobbyrydell.com.

|