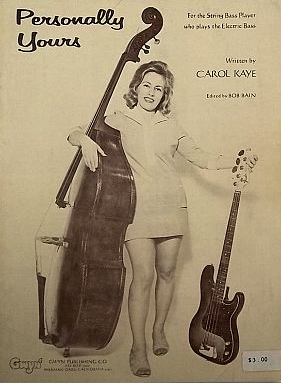

CAROL KAYE:

Her Bass Built a Foundation for Countless Rock 'n' Roll and Pop Classics

PCC's Vintage Interview with the Female Member of The Legendary Group of Studio Musicians Often Referred to as... The Wrecking Crew

By Paul Freeman [2002 Interview]

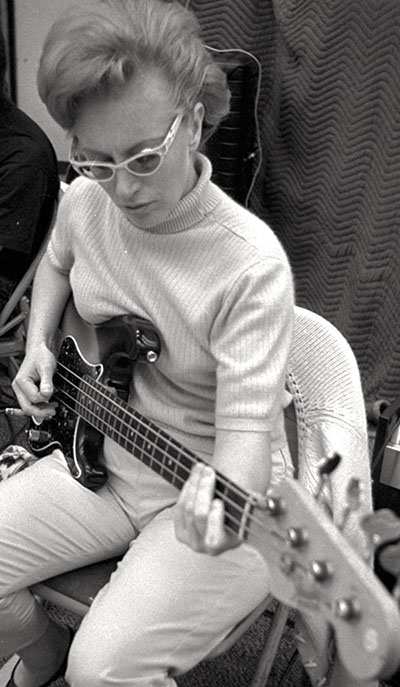

When it came to musicians, the recording studio was a man's world. Then came Carol Kaye. Playing guitar and then Fender bass, this extraordinary artist was part of the core of L.A. session players who helped to forge the sound of the 60s and 70s.

Kaye's distinctive styles can be heard on the records of such diverse stars as The Beach Boys, Sonny & Cher, The Crystals, Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, The Monkees, The Temptations, The Supremes, Dick Dale, Simon & Garfunkel, Sam Cooke and The Righteous Brothers. You'll recognize her bass lines shining on such classics as "These Boots Are Made for Walkin'," "Wichita Lineman" and "The Way We Were." Also contributing to numerous film scores, Kaye worked with such composers as Lalo Schifrin, Quincy Jones, Michel LeGrand, Elmer Bernstein, Leonard Rosenman, John Williams, Alfred Newman and Lionel Newman.

Kaye, who graced thousands of sessions, appears in Denny Tedesco's documentary, "The Wrecking Crew."

POP CULTURE CLASSICS:

Looking back at all those sessions, do they mostly just blur together?

CAROL KAYE:

There were literally hundreds of people that we all worked for back then. I usually don't remember specific tunes. I mean, I played on about 140,00 tunes. So there aren't too many that I remember. There was a lot of work back then.

PCC:

Did each member of the group establish their own style?

KAYE:

Well, when it was Billy Strange who was playing a rock guitar solo -- or Glen Campbell -- you knew it. It was a different style.

PCC:

Were some of the artists daunted, when they came in, by the chops and knowledge of all these great musicians? Some of the pop stars were more entertainers than musicians.

KAYE:

I mean, that's one thing that you noticed right away, whether they could play or not... because usually they couldn't. We were hired guns to sit there day and night getting hits for everybody and most of us were from the jazz world. And I think that was probably intimidating. When you walk into a date and you see the great [guitarists] Howard Roberts or you see Barney Kessel sitting there... And you're sitting there to play maybe a two or three-chord tune, it's got to be a little daunting to the rock star.

PCC:

And they would begin to see all it took to put a hit record together.

KAYE:

It was a big business. I mean, the engineers were in on it, the arrangers and all that stuff. The copyists even. It was a big business. It's got to be daunting for a new star. Some of them handled it better than others.

PCC:

Did you try to tailor what you were going to play to the star's vision?

KAYE:

There might be some suggestions made and then we worked off of that. And we listened to what somebody was playing and we kind of captured the style and just built a framework around that, yes.

PCC:

And I guess a lot of them knew what they wanted, even if they didn't read music and couldn't communicate in terms of theory.

KAYE:

You didn't need to. As soon as you hear somebody play, you get an idea of -- that's what they want. And we would build the arrangement around that.

PCC:

And the group could work quickly and still create great music.

KAYE:

Oh, yeah. We could cut a hit album in six hours. They were two record dates. The record date was three hours long and then you took a break in the middle for about a half-hour. If you wanted to go straight through, you could do that. But then they would have to pay us time-and-a-half, see.

PCC:

Really taking care of business, in terms of efficiency.

KAYE:

Let's put it this way -- we were not on drugs. The studio musicians were not on drugs. Never on drugs. In the 1960s, we could cut a hit album in about six hours for everybody. That is about five tunes a date. We could do that. Yes. I mean, that was our job.

PCC:

So no need for tons of takes.

KAYE:

[Laughs] Uh-uh. I mean, Phil Spector liked to work one tune a date. He liked to take his time and make 20 or 30 takes. And guess which take he'd wind up with -- probably take four or something like that. No, you don't have to sit and learn the music. That's why you get the competent studio musicians. I was making more money than the President of the United States, just doing that work. They were paying us doctor's fees. And that's what we made.

We made darn good money. But we were the best around. We had been out there playing gigs and concerts for years, before any of us did studio work. So playing all styles of music, we could do that. Our ears were good and we always had blank paper, so that we could write things down, if we needed to. Because a lot of times, you'd come up with a lick and it'd be gone. So you have to write it down.

PCC:

It must have been a strange feeling to see some of these people who didn't have so much talent come and become such celebrities, when you were the ones who gave them the hit sound.

KAYE:

Well, we did know how to make a hit record. And it takes a little while to learn how to do that.

PCC:

How did you get into the session work?

KAYE:

When I first started, I was a jazz guitar player, playing in a lot of the black clubs in the late 50s. And then somebody walked in and said, 'Do you want to do a record date?' It was close to Christmastime. I never wanted to do studio work, because I didn't want to lose my place in jazz. I was starting to make a name for myself. And I was playing with the best jazz players in Los Angeles. I was playing in all the clubs and my name was really getting up there.

I mean, my playing was good. My soloing was excellent. And so Bumps Blackwell walked in this nightclub and introduced himself, wanted me to do a record for Sam Cooke. I said, 'No, I don't want to do studio work.' [Laughs] But the rest of the guys seemed to like him. He seemed to be on the square. And I started to do the record dates in December of 1957, playing in back of Sam Cooke. And I made more money in one three-hour period than I did the whole week. So I said, 'Okay, I'll do studio work.' Because I had kids to take care of and I had no income. So one thing leads to another and I was doing studio work.

PCC:

And segueing from guitar to bass?

KAYE:

After about five years of being a guitar player on sessions, the bass player didn't show up and so, in '63, I started to record on bass. And it was a lot more fun than playing guitar, because the surf rock was starting to hit. And I couldn't stand that surf rock.

PCC:

Why?

KAYE:

I just couldn't stand it, because you were doing the same tunes over and over.... not the same tunes, but, being a jazz player, I was starting to miss jazz on guitar. But with the bass, I could play anything I wanted to and that was kind of fun back then.

PCC:

You certainly recorded with an incredible array of people...

KAYE:

Well, there was a lot of recording. I was the number one call, yeah, there for many years. In Los Angeles. Because I created certain sounds and styles. And, of course, I was there on time. [Laughs].

PCC:

Eventually the scene changed?

KAYE:

The way that it started going downhill was in the 70s, because then the younger players were into smoking pot and they were into doing cocaine. I mean, in the 70s, you could see that some of the guys in the booth insisted that the people in the band did drugs with them. But by that time, I was doing a lot of movie calls and TV stuff and I was turning down a lot of work then, because I didn't want to be around drug people. The group of us that cut the hits in the 60s were not on drugs at all.

Coffee was our drug. I mean, we were drinking 10 or 12 cups of coffee just to stay awake all the time, because we were losing sleep. And a lot of times, it would get boring, because you're sitting there waiting for them to fiddle with something in the booth or they're trying to figure out what to do with the song. But we could always come up with creative things. And that's what we did.

PCC:

When you launched into your work with the Wrecking Crew, were you the only female member?

KAYE:

Yeah, well, back in those days, they had a lot of women that were playing jazz, that were live. So it's not like there were no women who could play. They were out there playing live jazz in the 50s. But in the studio work, yes, I was the only woman in the rhythm section.

And, by the way, none of us were known as The Wrecking Crew back then. That was purely made up later on, in 1990, for Hal Blaine's book. He pushed that name to sell his book. None of us were known as that.

First of all, there wasn't a crew. We were all independent and we all worked with each other. There were about 60 of us that were known to be the hitmakers. But a lot times, we were called the Clique. But we were never called The Wrecking Crew. I never heard of that until later. And Jack Nitzche wrote about that, too. And others would say the same thing. We don't like what Hal Blaine tries to do with that term. Just to let you know.

Hal thinks that's the name that we were known by, because of his book. And Hal would love to talk about that on the TV. But to be honest with you, Hal's book didn't sell at all, which is a shame, because it's not a bad book. But he doesn't get into the nitty-gritty of the way we cut the music. Earl Palmer's [the great drummer] got a good book called "Backbeat" and he did just as many record dates as Hal Blaine, in fact maybe more, because he played on a lot of hits before he even came to L.A. in 1957.

PCC:

In those years, you also must have worked quite a bit with the sax great, Steve Douglas.

KAYE:

Oh, Steve was the number one sax player that did what you call the chicken sax or the rock 'n' roll sax solos. He's the one that would do that stuff. I mean, Clarence Johnson did a little bit of that. But mostly Steve. He was a very good sax man. And good guy. He was in there all the time. We all felt terrible about him dying so young. Terrible. He was smoking a lot.

See, a lot of those guys smoked. Ray Pullman [bassist] smoked, too. And he died at a fairly young age, too, from the heart. You just couldn't do all that smoking. And the coffee, too. The coffee got a lot of those guys, too. Unfortunately.

PCC:

Were you tempted to tour with some of the artists you did sessions with?

KAYE:

None of us really did tours or anything, because you'd make a lot less touring. And we were all raising families then. And if you take off from studio work, it's hard to get back in.

PCC:

Well, yours is certainly a remarkable story. You should write a autobiography.

KAYE:

Actually, I'm working on that right now.

Carol Kaye's autobiography, "Studio Musician: Carol Kaye, 60s No. 1 Hit Bassist, Guitarist" is now available. You'll find it, as well as instructional books and videos, plus much more, on her website, www.carolkaye.com.

|