|

CHRIS HILLMAN: A BYRD OF MANY FEATHERS The Singer-Songwriter-Musician Has Soared with The Byrds, Flying Burrito Brothers, Manassas, Souther-Hillman-Furay Band Desert Rose Band, Hillman & Pedersen, As Well As Flying Solo The PCC Vintage Interview

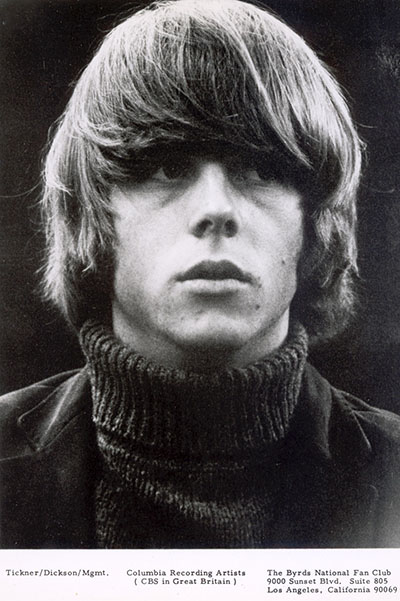

By Paul Freeman [2008 Interview] When you think of country-rock pioneers, Chris Hillman's name quickly springs to mind. coming from a bluegrass background, he joined The Byrds and helped the band meld rock, folk and country influences. His talents as a singer and songwriter grew, complementing his skills on guitar and mandolin. Hillman went on to contribute terrific music with The Flying Burrito Brothers, Manassas (with Stephen Stills) and Souther-Furay-Hillman Band. But his gifts blossomed most beautifully with Desert Rose Band, creating a string of hits in the 80s and early 90s, including "Love Reunited," "One Step Forward," "He's Back and I'm Blue," Summer Wind," "I Still Believe in You" and "She Don't Love Nobody." Hillman and the band attained elite levels with both their instrumentation and vocals. Pop Culture Classics interviewed Hillman in 2008. He has continued to perform and record. His most recent album, as of this writing, is 2017's wonderful "Bidin' My Time." Pals guesting on the record included Roger McGuinn, Tom Petty (who produced), Benmont Tench, John Jorgenson, Herb Pedersen and David Crosby. In recent years, Hillman has played reunion shows with Desert Rose Band. And, in 2018, he has toured with Roger McGuinn, backed by Marty Stuart & His Fabulous Superlatives, in a celebration of the 50th Anniversary of The Byrds' landmark "Sweetheart of the Rodeo" album. Even in his 70s. Hillman sounds fresh, youthful and vibrant. POP CULTURE CLASSICS: CHRIS HILLMAN: I only pick the ones that I really feel are relevant -- "Sin City" was a relevant song, in that I'm proud of being a co-writer on that. Each verse sort of mirrors the time that we wrote that. That was a song that actually wrote itself. Gram Parsons and I wrote that in 1969. And it probably took 30, 40 minutes to write that song. I had half of it written and I woke him up. We were sharing a house. And we finished it real quick. Interestingly enough, I was singing it a month or two ago and nothing really changes. Certain verses in "Sin City" relate to our culture right now. So I do draw on the stronger things from The Byrds through Flying Burrito Brothers and Manassas. Not Souther Hillman-Furay. Being honest with you, there's nothing that stands out as some great piece of work there. I think Richie did a couple of really good tunes. Actually, I think he probably did the best songs in the band at the time, certainly the most commercial. And then I do some Desert Rose Songs, because that was really the band I enjoyed being in, of all of the bands. That was the culmination of all of it, for me. PCC:

HILLMAN: PCC: HILLMAN: I loved the Gene Clark book. There were things in there I never knew about Gene. For me personally, I never knew certain things and I read that book and I went, "My God!" As much as I loved Gene, he had more opportunities given to him than just about anybody. But he would always manage to shoot himself in the foot. He kept getting these wonderful record deals. And he was very gifted. But the inner demons sort of took him... I don't know, that's another discussion. PCC: HILLMAN: It was like The Burritos. I ran the band. I did the business. I did everything. But I allowed Gram to do more of the front stuff. But in hindsight, I wished that I hadn't, because with The Burrito Brothers, it became a better band when he was gone. It was really a good band and it's evidenced on a record called "Red Hot Burritos," which is a live album, which is something we never could have gotten close to with Gram in the band. But Gene, I thought, initially, in the early years of The Byrds, the first year of The Byrds, he was a strong, powerful presence, as both a songwriter and live performer/singer. His presence was just very, very strong. I have a theory that sometimes when one part of the original package leaves, a little bit of the essence is gone. You know? Sometimes it's recoverable. Sometimes it isn't. We recovered pretty well, when Gene left. We did a lot of good albums after that, ending up with "Sweetheart of the Rodeo." Same with The Rolling Stones. To this day, I think they haven't sounded as good with Bill Wyman gone, the bass player. I thought Bill added something that was part of the whole energy that was lost when he left. PCC:

HILLMAN: PCC: HILLMAN: I'm still learning. I'm still learning how to play. I've always loved that old comment in journalistic circles -- "master of his instrument." You don't master anything. There's constantly something you can learn. And even if it's not musically, it's something. Anything. You learn something every day. And the road to success is full of mistakes. I think I put in a long apprenticeship [laughs]. I put in a good apprenticeship. But then, as I say, I loved every group I was in, even SHF, to some degree. It's not high on the ladder. It's not on the upper levels of the ladder of my life. But then the last real band I was in was Desert Rose and that was really something. But then that was really not in rock 'n' roll at all, but in country music. And we were accepted in the country music community for who we were. It wasn't because I was in The Byrds. It had nothing to do with it. We were accepted for what we did. There were country music fans that had no idea who The Byrds were or any of those bands. And they accepted us. So that was the pinnacle. Not the pinnacle, because the best things are around the corner, I think. PCC: HILLMAN: PCC: HILLMAN: PCC:

HILLMAN: And that's what sort of put the pressure on Desert Rose. And one of the worst records we made -- with all the pretty good records we'd done, been pretty consistent -- the one time we fell was when we listened to MCA and we changed producers and let somebody at MCA produce us. And we listened to him and we lost our edge. Instead of following our own heart and our inner voice, we made a terrible record and it started the spiral of trying to regain ground. We had lost a lot of ground. It was a record called "True Love." [1991] It was towards the end of the band. And that was the one time I said, "Why did I ever... [laughs] We were doing great. Why change it? PCC: HILLMAN: The Byrds were a good band that developed into a very tight, wonderful recording band. Our live performances were spotty. But all in all, The Byrds' performances were really good and tight. But going into The Burritos, it was pretty ragged at first. So we were sort of caught there. But that looseness somehow appeals to all the alternative country bands or independent rock bands. And the Gram Parsons cult worship thing mystifies me. I loved the guy. I had a great year working with him. One year. But I don't know if I would classify him as some outstanding genius. And I certainly don't think he was a role model to anybody. Role models don't behave that way. You don't need to punish yourself to create a great piece of art. It never works that way. PCC: HILLMAN: PCC: HILLMAN: PCC: HILLMAN: PCC: HILLMAN: And I hooked up with Stephen and did some sessions for him. And then he had the idea of putting that band together [Manassas]. And that looked like another interesting situation. In the scope of things, that was the thing to do at the time. PCC:

HILLMAN: However, there were moments... and there were actually some decent shows we did. I don't look back at that particular era of my career as being one the most important, the defining moment in my life. I like Furay. I like Souther. I mean, J.D. Souther, a wonderful songwriter, probably the best out of the three of us. PCC: HILLMAN: PCC: HILLMAN: PCC: HILLMAN: I don't mean to be on a soapbox about this, but I'm a big proponent of the family. You can cure a lot of society's ills in this country by just keeping the family unit together and communicating. So I did take time, but I was still active. I guess the more I say I'm retired, the more the phone rings. It works pretty well [laughs]. Anyway, at that time, Desert Rose, we weren't getting on the radio anymore. This was when country music was taking a strange turn around 1991, '92, '93. A lot of acts in Nashville were having trouble. Garth Brooks came out. There was this whole wave that came in. And all the hat acts came in. And Billy Ray Cyrus. And line dancing. It was a new environment. And a lot of the singer-songwriter element that had developed in Nashville from about 1986 started to fade away. And I said, "I think our shelf life has started to expire. We're not getting the same offers and we're not getting on as easily." I don't blame Garth Brooks. That's just the way it was evolving. And on my personal level, I felt I'd been on the road so much... in country music, at the time, you were on the road a lot longer than you were in rock 'n' roll, as far as days out. And I thought it was time to just put it to sleep. Things are starting to change back a little bit. I think Nashville's reassessing everything with the success of that "O Brother Where Art Thou" soundtrack. It sold so well because people wanted to hear that kind of good music. So Desert Rose was the only band that parted company without any animosity. We ended it amicably. Everybody just said, "Okay," and off we went and did other things. It was nice. It was a nice parting. We're all still friends. I still work with Herb [Pedersen] and Bill Bryson. And I talk to John Jorgenson all the time. I work with all of them off and on, on various little projects. So that was nice. And in all honesty, Paul, I have great love for all the people I've worked with. I don't feel ill feelings towards anybody. I get along with David Crosby and Roger McGuinn and everybody... and I assume they get along with me [laughs]. I don't hold any grudges or anything. I'm lucky I'm here. I'm lucky I'm healthy. And I have a good family. My daughter is 22. She's starting as a high school English teacher. My son is going into Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, on an Ag program. And his major is Viticulture. You could very well be drinking his wine in seven or eight years. He's been learning winemaking. I felt that raising two good kids that are bright and moving forward far surpassed anything I did musically. I felt that was a bigger accomplishment, personally. And I still can work, if people want to hear me. And if it stops tomorrow, that's okay. I've had a good run. PCC: HILLMAN: You know, I lost my dad when I was 16. When he died, we were really destitute. I had to go to night school to finish high school. It was really hard. But the first 12 years of my life, what kept me out of the complete chaos, or why I'm not a statistic, I was taught and brought up with a very good sense of morality and values. I had a very good and close family, a very affectionate family. My brother went on to become an Air Force officer and retired after flying for Continental Airlines for 25 years, retired as a Lieutenant Colonel in the Air Force, also was an airline pilot. My older sister was, for 30 years, a school teacher in the San Francisco school district. My younger sister was a school teacher. I did my music. We all moved forward. We were taught that. What I'm trying to say, it's not about my personal life, but I think you can pretty well survive all obstacles thrown in front of you. It's all down to you making those choices. But being taught what is right and wrong pretty much will stick with you through some pretty tough times, as you grow older. I firmly believe that first 10 to 12 years are important. I firmly believe now in a strong Christian-Judeo foundation in the family. But that's not something for me to proselytize or convert or tell anybody what to do with their lives. We grew up in a sort of semi-Protestant home. But it was not overbearing. We'd go to church four times a year, maybe. My dad was a total atheist. However, he still was a good dad and taught us those values. And that's what's missing these days. He taught us to be responsible for our actions. And that covers a big gamut of things. And that's something that our society now is stumbling along where people aren't being responsible for their actions, if you know what I'm saying. You wonder why there's so much crime, wonder why there are so many kids doing this and that. There's some wonderful kids out there, too, that are educated, that are going forward. But we have a lot of problems. And a lot of it is just this lack of responsibility. Let's put it this way, if you decide to have children, and you're a young couple, priorities change. And that's the biggest decision you have to make. When you decide to have those children, all of a sudden, it's not about you anymore. It's about those children. Now, I chose a career that is basically me-oriented [laughs], the entertainment business. It's me, me, me. And unfortunately, that particular business draws one into some tempting lifestyles. And I'll never accept when someone says, "Well, substance abuse is a disease." It's a disease of selfishness. It's "Me. How do I feel better? And I don't care how you are or what you are?" And that's the disease that takes over. And that can be even non-substance abuse-related, where it's, "I have to reach the golden ring. I've got to be the best. And I've got to get this and that." Well, we all want to be the best at everything -- but not at the expense of others.... Am I preaching to you now? PCC:

HILLMAN: I told you about "Eight Miles High." The reason I did "It Doesn't Matter" was because I didn't really like the way Manassas cut it. And I thought it was a great song. So we did it a little differently, did it a little faster, but basically the same arrangement. I wanted the CD to be something that would take somebody out of the world for a while and relax them -- as simple as that sounds. That really was the idea. It wasn't dealt with as a concept record. It just sort of came out that way. PCC: HILLMAN: I felt terrible. But I couldn't allow her to listen to that. I said, "We never wrote songs like that." We implied things. But we never had to graphically describe everything. It's like somebody who constantly, every other word is a swear word. We all know people like that. I look at them and say, "This guy has a limited vocabulary. There's a show on HBO, "Deadwood." I love westerns, because I grew up with horses on a ranch. But "Deadwood" bothered me, because every other word was c-sucker this and that. First of all, nobody really spoke like that in the 1880s. I'd go on record on that. But second of all, that offended me. That could have been a wonderful show. They didn't need that language. It really bothered me. I wanted to like it, because I'm fascinated with that period of history. But that just turned me off. That's bad writing. Unnecessary. Rock 'n' roll back in the 50s, what did that phrase originally mean? It meant making love. That's what it was. And it was a black term. That's why Pat Boone would come out and record all of Little Richard's songs [laughs]. Whitewash 'em out. Richard got away with a lot. So did all of the rock 'n' roll guys back then. But it was just the way it was. And they got away with stuff. But it never was in your face. It was so tame back then. It never was over the line of decency. And some of these songs now, they're advocating violence. They're disrespectful to women. I'm generalizing, mind you. But I'm going, "Why have we developed a culture that rewards bad behavior?" Why is Paris Hilton newsworthy at all, when there are other things that are far more newsworthy? As a society, as a country, I can safely say that in eight, nine, 10 years, newspapers could easily be a lost art. There would be no newspapers left. We've just developed this celebrity worship, this strange superficial look at life. PCC: HILLMAN: PCC: HILLMAN: The first year in The Byrds, I was just playing bass and when the three of them would hit that three-part harmony, it would just take off. What a feeling. PCC: HILLMAN: And then you've got reality television shows. I don't even go to the movies anymore because, most movies that come out, I don't like them. I love old movies, because there was better writing, great scripts. I want my imagination. And my imagination has been taken away by a culture that went awry somehow, where we've been stripped of our imagination. And I'm not talking from conservative censorship or anything like that. It's not that I'm just condemning over-gratuitous sex in films... or violence. It's that I don't have my imagination to imagine that happening. Here's my best analogy. In a movie, I would rather see a man and a woman walking into a bedroom and she kicks off her shoe -- if you can visualize it -- and the door slowly shuts. It's sort of a dark scene through a window or something. I can use my imagination for all of the above. And Violence. Too much violence in movies. It's too disturbing on the street as it is. But what is that message to younger kids? I'm 63 years old. I can look at it and say, "Okay, yeah, don't act like that." But what does a 15-year-old kid that's having problems at home think? Back to square one, Paul. What's going to keep the civilization together is the family. Of all the great civilizations over the last 5,000 years, where have they lost it? They've always crumbled from within. The morals have gone out the window. The moral compass breaks and the civilization crumbles from within, allowing whoever to come from the outside and just take over. We're dealing with it right now in this country. I'm not predicting a Doomsday scenario. I have great faith in this country. I have great faith in the young kids I see. Most of them are wonderful kids. Where does this all fit with music? Well, I'm not going to write lyrics that are going to say, "Go out and kill a policeman." I'm not going to call a woman a bitch or a whore. I'm not going to do that. Nor do I need to. Nor would we ever have done that in the 60s. Good art is subtle. Once again, why is that? Because it leaves it to your imagination. You have your own subjective look at that art on a wall or that piece of music that you're hearing through your speakers or the book you're reading -- good art is subtle. It's drawing you in and giving you certain things to form your own opinion. Yes, there is a general meaning that the author or the artist is trying to convey. But to just lay it out there -- I mean, I'm looking at things on television -- what's next? The Execution Channel, where you'll watch people being executed? And it's not that crazy. Right now, I'm looking at these Ultimate Fighting things that are on TV and I love boxing. I was a boxing fan. Still am. But the Ultimate Fighting leaves nothing to the imagination. You're seeing two guys brawling on the floor, inside the cage. That doesn't do much for me [laughs]. Going back to music -- and there's a point to this rant I've been going on. Going back to the music, what was really wonderful was the early days, especially the early 60s, which I liked, up until 1968, when we, as a country, as a culture, took a great strange turn. The drugs became weird. Drugs became a business, a profitable business. 1968 was the year that King and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. And George Wallace was shot. There was this anarchy going on. And the colleges -- Yes, kids have a right to protest and yes, Vietnam was a complete debacle. Looking back at the 60s, to quote somebody I heard the other day, it's not my line, "the era that ushered in the age of stupidity." My generation's parents went through the Depression and World War II. The 50s were prosperous. There were a lot problems, but not to the degree we have today. Then along came the 60s and we, my generation, were trampling down -- I'm looking back at it now, as an older man -- we were stepping on all of the things that really had some depth and substance, traditional family values and caring for one another, and manners, and respect for people. I went through the entire California school system, never talked back to a teacher. You were taught. I got a good education in California schools in the 50s and 60s. But I was taught respect. And I knew, when I was growing up, if I did some stunt and one of the neighbors saw me, not only would I be disciplined by that neighbor, I would get it later from my mom and dad, because it was a time of, once again, great respect for one another. I don't yearn for it. I can't go backwards. I've got to deal with what it is now. But I certainly try to instill the things I was taught into the kids I brought up. I think a lot people who grew up when I did would say the same thing. A lot of the dads came back from World War II and they were in the midst of horrendous situations at 17, 18 years old in Europe or the South Pacific. And a lot of them came back with major problems. But in those days, you didn't go and get therapy. You just sort of stoically went through your life and you raised your family, did what you had to do. But all in all, it was just a gentler time. But there it is. And here we are now. PCC: HILLMAN: PCC: HILLMAN: My dad thought I was insane [laughs] He used to say things like, "Are you sure this is our son, listening to Flatt & Scruggs? What is that? Are you my son? Why are you listening to this stuff? Are you from Oklahoma? Well, if you like it, that's okay. I guess there's something to it." [Laughs] But the poor guy didn't live long enough to see the fruits of my labor. There was just something about the singing. My sister had gone to university in 1953 in Colorado and about 1957, '58, she got me listening to not only the rock 'n' roll that was out, which was really great stuff at that time, but also turned me on to some really interesting folk stuff a la The Weavers and Pete Seeger, things like that. So there was something about the singing. And when I heard bluegrass, it caught me, that high-energy, improvisational approach. And yeah, it was predictable stuff. You always knew A equaled B in bluegrass music. But that high energy just hit a nerve with me. It really hit me around 1960, as a high school kid, same time it hit people like Herb Pedersen and David Grissom. Herb grew up in Berkeley, David in New Jersey and I'm in San Diego. Somehow that strange sound hit a nerve and set that off. PCC: HILLMAN: And Scott Hambly, where I had seen him play was, he was filling in with The Kentucky Colonels down in Los Angeles at the old Ash Grove coffee house. And he was filling in for Roland White. PCC: HILLMAN: If you were lucky enough to see "The Atlantic Records Story" on PBS about Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler starting Atlantic, these guys loved music. And they made the records. They went out and found the talent, made the records, went to the radio stations. And that's the part of it that I love, where I got into it in the early days of the business and we were allowed the artistic freedom. And I think where the music business really started to become a business was after the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. I think all these guys went, "Hey, we can make a living. We can make a lot of money at this." That's where it took off. But it was still very artist-oriented up through the 70s into the 80s, where the artists, they'd stick with you. If you didn't sell platinum out of the box, it didn't matter. Nobody sold platinum in those days. You were lucky if you got a gold album. But they would stick with you, three or four albums. They would nurture you along. It was a different time. It wasn't a situation of dealing with the corporate monster. When you're a young person starting out, dealing with pop-oriented videos and this and that, if you don't deliver on sales the first time out of the chute, you're going to be dropped. So it's not necessarily the artistic endeavor that it used to be. Push the boundaries? Yeah, we did. But I did what I felt in my heart. I did the kind of music that I wanted to do. Sometimes I did make concessions, working with other people. But all in all, I followed my heart, what I really liked, what really hit a nerve with me. I stuck with that. And there's nothing that I like better than getting up on stage and singing with Herb or whoever, in an ensemble vocal setting. I mean, I sing in a choir every Sunday, a really good choir, Greek Orthodox. I don't speak Greek. It's all Byzantine. It is completely different from what I do on stage. But I read the Greek phonetically and I do the liturgy in the Greek Orthodox church and I'm probably the only hillbilly tenor in the Greek Orthodox church, probably in the whole country. But the point is, I love doing this. I love to sing. And here's a guy that was the shyest guy in The Byrds, who couldn't sing worth a darn 44 years ago. And now it's probably my strongest suit, over my mandolin playing or my guitar playing. I love doing it. But like I said, Paul, if it ends tomorrow, I had a great time. I was a lucky kid [laughs]. I mean, there were a lot better players out there and a lot of people that never quite got the opportunity. I was a lucky guy and I feel blessed to have lived through those days. PCC: HILLMAN: I was the bass player in The Byrds. I loved playing bass on that stuff. I wasn't the lead singer. Roger McGuinn was. And he did a great job at it. He's very good. He has a wonderful style. And the records stand up. And the thing you look for, Paul, is you want to try and do something that's as relevant 20 years later as it was at the time you did it originally. The stuff we did with The Byrds, most of it stands up pretty well today. PCC: HILLMAN: Rap, there's probably some of it's that's pretty good. But where's the melody? It's not melodic. And I've always appreciated a real strong melody. PCC: HILLMAN: But then again, I hear some stuff out there. There's this girl Tift Merritt, we did a live PBS show with her in Nashville a while back, and she was very good, her take on life, as it was for her at that point in her life. But keeping it fresh? Yeah, it's always hard to do that. I'd like to do more story songs, stories that are timeless. I was listening to this box set of Johnny Cash the other day and I'd forgotten how good he was. I was listening to this old stuff. "Don't Take Your Guns to Town." "Ira Hayes." All this stuff. Wow! What an interesting man. Look what he's done with his life and the songs that he's written. Such great story songs. PCC: HILLMAN: We left an amazing path for other bands to follow. You hear so much of The Byrds influence in other bands. It was like we handed it off to somebody else. And I even can say that about Desert Rose with the Nashville thing. I sort of listen to the Nashville bands and I hear what we left as sort of a little bit of a legacy musically for other bands. And that's your ultimate compliment -- to be copied, in a sense. It certainly didn't hurt Tom Petty a bit, did it? I like Tom's music, I really do. And he would be the first to admit The Byrds were a huge influence on his early records. There's a funny story about one of his first hits -- "She's an American Girl." And back in the 70s, when Tom first had a hit, Roger actually, at one point, thought he had recorded it [laughs]. It sounds so much like him. "Did we record this? Is that one of our records?" But there it is -- that's all you can hope for. Success is not looking at your bank balance. Success is doing something that you really love to do and to be able to do it. Hey, I might be in one-half percent of the country that gets to do something they like and gets paid for it. Maybe there's a little bigger percentage, but you know what I'm saying. It's like kids going into college, their majors. You see lots of Business majors or law school kids. And the question they have to ask themselves is, "Is this something I really want to do or is it just to get things?" That's an interesting thing. When I started in music, and I can speak for everybody that I knew then, from Crosby to... I can speak for them right now. We went into music because it was a passion. We loved it. We never thought we'd make any money. There was no MTV spewing out all that garbage at us, telling us that we'd have limousines and girls and all of that. Yeah, we knew that, if we played the guitar and sang, we might have a better chance at meeting some pretty girl [laughs], but it was all about the passion for the music. I never thought I'd make a living. I thought, "Well, I'll do this for another six months and try to get back into school or something." I had an idea about becoming a History major back then. And I read it on my own. Never did go back to school. Hey, things worked out okay. For the latest on this artist, visit www.chrishillman.com. |