CYNTHIA WEIL: HER LYRICS HAVE TOUCHED OUR LIVES

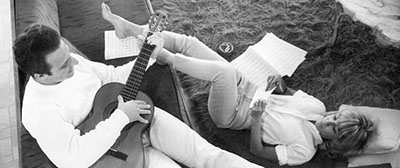

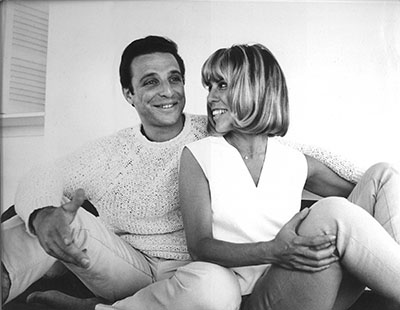

With Husband Barry Mann, She Co-Wrote Timeless Hits Like “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’.” Now She’s Moving Readers With A New YA Novel, “806.”

To say she has a way with words is a colossal understatement.

Cynthia Weil’s elegant, expressive song lyrics helped to reflect, shape and define a generation. With her husband Barry Mann providing gorgeous melodies, they crafted hits that have proven to be timeless, among them, “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,”Soul and Inspiration,” “We Gotta Get Out of This Place,” “Kicks,” “I Just Can’t Help Believing,” “I’m Gonna Be Strong,” “Here You Come Again,” “Somewhere Out There,” “Don’t Know Much” and “Just Once.”

The story of Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann’s early days in New York is a huge part of the smash Broadway musical “Beautiful.” The show focuses on their best friends and songwriting rivals — Carole King and Gerry Goffin.

Though partnered with Mann since 1961, Weil has also successfully collaborated with other songwriters, including Lionel Richie (“Running in the Night”) and David Foster (“Through The Fire”) .

The award-winning Weil’s lyrics have been brought to life by diverse artists, including The Crystals, The Ronettes, Jay & The Americans, The Drifters, Eydie Gorme, The Vogues, Mama Cass, Paul Revere & The Raiders, Gene Pitney, B.J. Thomas, Linda Ronstadt, Dusty Springfield, Dolly Parton, Aaron Neville, Peabo Bryson, Chaka Khan, Bette Midler, Martina McBride and Elvis Presley.

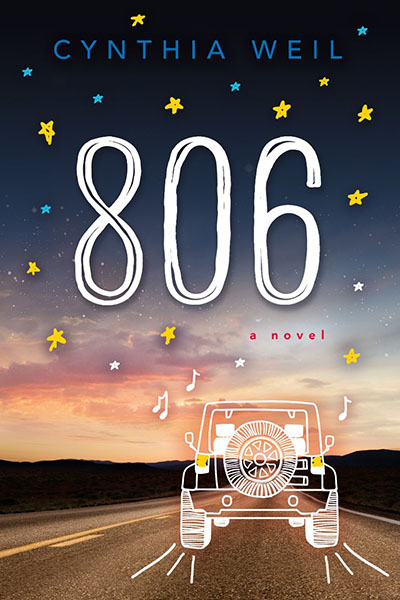

Weil’s imagination and eloquence have graced more than lyrics. Having explored several forms of prose, Weil has turned her talents to Young Adult fiction with the new “806: A Novel” [Tanglewood Publishing]. The result is compelling, funny and touching.

In the book, teen Katie, an aspiring rock songwriter/musician, at odds with her mother, learns that her biological father was an anonymous sperm donor. She only knows him as number 806. Investigating, Katie — or KT, as she demands to be called — discovers that 806 fathered two other kids from her school. They turn out to be a nerd and a jock. They’re all disappointed to see who their siblings are, but reluctantly, they team up in search of their mysterious dad.

What follows is a road story filled with unexpected adventures… and misadventures. The three seemingly disparate teens gradually realize that there’s more to each of them than meets the eye. During their cross-country quest, they find they have more in common than they could have imagined. As they overcome obstacles together, a unique bond is forged.

Pop Culture Classics readers should definitely pick up a copy for the teen in their lives… or for themselves! It’s an entertaining and meaningful ride for all ages.

Ms. Weil graciously agreed to talk with Pop Culture Classics about both “806: A Novel” and her songwriting career.

POP CULTURE CLASSICS:

The new book, “806,” is a very enjoyable read. What made you decide to enter the realm of Young Adult fiction?

CYNTHIA WEIL:

I guess I’m just immature. [Laughs] I don’t know. I guess I just love teenage angst. I guess it was reflected in my songs and now it’s reflected in my book-writing.

PCC:

That subject of children of sperm donors, how did that spark ignite in your mind?

WEIL:

That happened, because I saw an interview with a guy who had created all these children and they were all on a television program. And everybody loved everybody. And they were, as I described it in the book, kind of a spermy “Brady Bunch.” And I just wondered what would happen if three kids who didn’t like each other had to seek out their sperm donor father.

PCC:

Do you think that kids reading it, who feel any sort of sense of alienation, can relate?

WEIL:

I certainly hope so. I think everybody wonders, in their teenage years, whether their family is like everybody else’s. And I think it’s good for kids to know there are lots of kinds of families.

PCC:

Yes, you get the opportunity in “806” to explore a really unusual form of family bonds.

WEIL:

Right.

PCC:

Getting into the heads of contemporary teens, so you could create convincing characters, as you have done here, capturing the vernacular and the mindsets, what was that process like?

WEIL:

You know, I think kids are the same through the years. I just remember my teenage years as being very angsty. I had my own family issues. And I just wanted to create a family that was different.

PCC:

In the book, Katie, when she’s troubled, can lose herself in music. Did you have that, as an adolescent, with your writing, whether it was poetry or journals or whatever?

WEIL:

Yeah, absolutely. I definitely had that as an outlet. Certainly with writing. And I started lyric-writing very young. Even though I didn’t do anything with it, but I would kind of take existing songs and write new lyrics for them.

PCC:

How old were you, when you started doing something like that?

WEIL:

Probably my early teenage years.

PCC:

And were there particular writers or types of songs that most intrigued you?

WEIL:

I was intrigued by Vernon Duke [Broadway and film composer/songwriter; “April in Paris,” “Taking a Chance on Love,” “I Can’t Get Started,” “Autumn in New York”]. I was intrigued by Oscar Hammerstein [lyricist/librettist; “Showboat,” “Carousel,” “South Pacific,” “The King and I,” “The Sound of Music,” “Oklahoma!”]. I was intrigued by all the great show writers.

PCC:

At what point did you think this was something you might want to seriously pursue?

WEIL:

Kind of after I met my husband, who I thought was so cute that I wanted to do anything that would let me do something with him.

PCC:

You had connected with Frank Loesser before that, hadn’t you? [Loesser was the songwriter of “Baby It’s Cold Outside,” lyricist for “Guys and Dolls” and “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying,” operated his own publishing company]

WEIL:

Yes, I had. I met someone who knew Frank Loesser and sent me up to him and he had me writing at his publishing company for a couple of years. And I didn’t really get into it until I moved on to Nevins/Kirshner [Al Nevins and Don Kirshner ran Aldon Music, which had under contract many of the great Brill Building era songwriters and was initially located at 1650 Broadway].

PCC:

But the time at Loesser Publishing, was that a good learning experience?

WEIL:

It was a learning experience, but not learning how to write pop songs. The writers there were much more cabaret and Broadway and everything but knowing how to get contemporary records [laughs].

PCC:

So how did you connect with Barry?

WEIL:

Well, I went up to write with someone named Teddy Randazzo, who was kind of the Italian boy singer of the day. And when I went up there, Barry was up there, playing a song for him. And I just saw Barry and that was it for me.

PCC:

So there was instant chemistry, creatively and romantically?

WEIL:

Well, it started out with romance and moved into creativity.

PCC:

Did he suggest pop songs for you to study?

WEIL:

Yes, he did. He said, “Listen to The Everly Brothers. Listen to The Drifters. Listen to all the pop singers of the day.” And I absorbed.

PCC:

And what impressed you most about Barry’s musical gifts?

WEIL:

You know, it wasn’t his musical gifts. It was his cuteness. [Laughs]

PCC:

[Laughs[ That’s important.

WEIL:

[Laughs] Yes, especially at that age.

PCC:

Once you got into the collaboration, what was the process? Did you usually write lyrics first and then Barry would build a melody?

WEIL:

We worked all different ways. I used to like giving him a title or a feeling and he would come up with some kind of a musical basis that I could write to.

PCC:

When you were writing lyrics, did you ever get a snippet of melody in your head and pitch that to Barry?

WEIL:

Occasionally. [Laughs]. All I can remember right now [sings] “No, no, the Bossa Nova…” [from the Eydie Gorme hit “Blame It On The Bossa Nova”], which was mine. And then once he left me with a melody and I erased it by mistake. So I made up my own opening line and it was the opening line of “Here You Come Again” [the Dolly Parton smash].

PCC:

You would have thought that would have sparked more musical ideas, having that kind of success with a melody.

WEIL:

Well, it was the just opening line. The rest of it was his.

PCC:

The Broadway musical “Beautiful,” such a wonderful show, when they were still in the writing stage, did they consult you and Barry, get your insights and details?

WEIL:

Doug McGrath, who wrote the book, spent a couple of days interviewing each one of the writers. And Gerry was still alive then. So it was him and Carole and Barry and me. And I think we all contributed in that sense, in that we gave him the basis for what we wrote and the feeling of it. But the actual writing, we didn’t have anything to do with.

PCC:

Did you have a chance to read the book for the show before it opened?

WEIL:

Yeah, we did. And we had a couple of readings. And to tell you the truth, I didn’t realize it was as good as it was, from those readings. It wasn’t until I saw an audience respond to it that I realized how big it was going to be.

PCC:

And the first time seeing the full production, was it surreal to see yourself depicted on stage?

WEIL:

{Laughs] Oh, it was! It was absolutely surreal. But I got used to it very fast.

PCC:

And I hear there will be a film version in the not-too-distant future.

WEIL:

Well, yeah, I mean, I guess so. It’s been optioned, but I don’t know what’s happening with that yet.

PCC:

If someone had told you in the 60s that one day, your lives were going to be turned into a hit musical, you probably would have been shocked.

WEIL:

I would have been shocked. And I once put a picture of Carole and Gerry and Barry, sitting in our apartment, on the floor, acting like nuts, on Twitter, and said, “Who would believe that these three lunatics and their photographer would one day be depicted in a Broadway show?”

PCC:

So the four of you, the two teams, I guess there was great camaraderie and rivalry, as well?

WEIL:

Yes, there was. There was great friendship and great competition. And it was all mixed up, because we were very competitive and then we felt guilty for being competitive. And it was all crazy.

PCC:

And do you think that sense of competition benefited both songwriting duos, maybe providing some extra fire?

WEIL:

Oh, I absolutely do. We wanted to beat them out on every record. And we did our best. Sometimes they won. Sometimes we won.

PCC:

Is there a song of theirs where you especially went, wow, I wish I’d written that?

WEIL:

Almost everything they wrote [laughs].

PCC:

Did you discuss lyric-writing with Gerry Goffin much?

WEIL:

I really learned a lot from Gerry. He was kind of always a few steps ahead of me, I felt. And he wrote very compassionately. And I think I learned that from him.

PCC:

What was the atmosphere generally at 1650 Broadway [where so many of the era’s best songwriters were based]? It must have been an exciting time.

WEIL:

You know, we didn’t know it was an exciting time. We thought this was just the way the world was and it was going to stay that way forever. So I don’t know whether I can really answer that question.

PCC:

At that time, in the 60s, when things were happening so fast, were you able to enjoy that first rush of success? Or were you too caught up in everything?

WEIL:

We were too caught up in everything. I don’t think we enjoyed anything. I have a story I can tell you that kind of epitomizes the way it was. Do you know who Paul Evans was? He had a song called “Seven Little Girls (Sitting in the Back Seat).” It was a novelty hit. I bumped into him and he said, “You know, I have a story to tell you about your husband. I bumped into Barry, who was racing down Broadway to cut a demo. And I said, ‘Congratulations.’ And he said, ‘What for?’ I said, ‘Well, you’ve got three songs on the charts.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, but two of them are going down.’”

PCC:

So there was always the pressure to equal or top yourselves?

WEIL:

Yes, there was.

PCC:

For you and Barry, being creative collaborators, did that always enhance the personal relationship? Did it sometimes cause friction?

WEIL:

Yeah, sometimes I wasn’t sure whether he was annoyed at me because he didn’t like dinner or whether he didn’t like the lyric.

PCC:

Did you try to keep the two elements of your relationship compartmentalized or was that impossible?

WEIL:

Yeah, we did try. But it wasn’t easy. I don’t think we were very successful at that.

PCC:

You mentioned picking up the compassionate angle from Gerry. Was it important to you to write songs that really meant something, in some way, that were more than just catchy?

WEIL:

Oh, absolutely. I think Gerry was very aware of what was commercial. I wasn’t. I was just aware of what I wanted to write.

PCC:

With something like “Uptown” [a Phil Spector-produced hit for The Crystals], dealing with social issues, what was the seed of that song?

WEIL:

The seed of that song was I saw a guy pushing a cart with clothing on it in the garment district. And he was so handsome and tall and looked like a warrior. And I thought, his life is so different — uptown and downtown.

PCC:

And“On Broadway,” such a great aspirational song, how did that work, with you and Barry teaming with another legendary songwriting team, Leiber & Stoller, on that one?

WEIL:

Well, originally Barry and I had written the song for The Cookies, who were a group Carole and Gerry were recording. And it was from a girl’s point of view, being a girl from a small town, who wanted to come to New York and get out of that small town and make it on Broadway. When we got together with Leiber & Stoller, they said, “Well, you know, we’re looking for something for The Drifters. But we’d have to rewrite this. We’ll give you an option — you can do it with us or you can go home and do it by yourselves.” And we just thought they were the greatest, so we looked forward to writing with them.

PCC:

And that was a good experience?

WEIL:

Oh, it was great. Jerry [Leiber] was an amazing, creative writer. I just learned so much from him. I was very anal. I would have to finish a first verse before I could go on to a second. And Jerry would jump all over. He kind of loosened me up a little.

PCC:

“Only in America,” I read that the song, in the hit version, it was sanitized, in terms of the message. Is that right?

WEIL:

Yeah, well, originally, we had wanted to write it from the point of view of, “Only in America, land of opportunity, do they save a seat in the back of the bus just for me.” And Jerry Leiber said, “You’ll never get this played. He was very realistic. So we actually wrote it from the positive point of view. And when The Drifters recorded it, nobody would play it. It was so untrue.

PCC:

But eventually you had a hit on it with Jay and the Americans.

WEIL:

Yeah, they kept The Drifters’ track and put Jay and the Americans on it.

PCC:

And then “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” — such a great sense of urgency and determination in those lyrics. How did that take shape for you?

WEIL:

Well, we had originally written it for The Righteous Brothers. And it had much more of a Righteous Brothers feel. And we were dealing, in a sense, with Allen Klein, who later managed The Beatles and the Stones. And we left it on his desk and forgot about it. And he was managing Mickie Most, who was recording The Animals. Barry had recorded it himself to put out on Leiber & Stoller’s label, Red Bird. So our publisher, Kirshner, called us up and he said, “I have good news and bad news. The good news is, you have the number two song in England. And the bad news is, Barry’s record can’t come out.” [laughs]

PCC:

Did you take that philosophically?

WEIL:

No, I thought I would go crazy [laughs]. I tried to punch a hole in the wall. It was very, very disappointing, because I loved Barry’s record.

PCC:

But in the long run, do you think it was better that he remained focused on the songwriting, rather than the performing?

WEIL:

Yeah, I do. I honestly think that he was not as level-headed as Carole. And had he focused on the performing, I don’t think that we would still be married, because he would have been seduced by groupies all over the place.

PCC:

You did actually separate, at one point, didn’t you?

WEIL:

Yeah, we did. That was not so much because of groupies as it was because of cocaine [laughs].

PCC:

What era was that?

WEIL:

That was in the 80s. 1984.

PCC:

That was happening everywhere then.

WEIL:

Oh, it was. It was just crazy.

PCC:

So how did you get back together and make things work so well again?

WEIL:

Well, he got clean. And I missed him terribly. And we missed each other. So we started talking, little by little, and we decided that we should give it another shot.

PCC:

It must have been a double whammy — losing your writing partner and your life partner at the same time.

WEIL:

Yeah, it was. However, I was caught up in the midst of what they call “an agitated depression,” where I had this tremendous energy to write. So I wrote with a whole bunch of other people and actually had some hits [laughs].

PCC:

But then when you did finally get back together, was the bond even stronger? Was there a greater understanding?

WEIL:

Oh, absolutely. And the first song we wrote was “Just Once,” which I’m very proud of.

PCC:

The song “Walking in the Rain” was another beauty, a success with The Ronettes and then The Walker Brothers. What was the feeling in writing that song?

WEIL:

You know, I don’t know if there was that much feeling, to writing that song. It’s really done beautifully in “Beautiful.” But I always felt that it was kind of a baby song, you know? I didn’t feel that it had the sophistication and the other things that I was proudest of. But I’ve learned not to say that to people, because sometimes I will talk about a song and say, “Oh, that was a slump song. We wrote that when we were in a slump.” And they’ll say, “Oh, my God! That’s my favorite song!” [Laughs]

PCC:

Can you separate whether it’s a great song or a great record?

WEIL:

Yeah, sometimes we can. I don’t know that it can be a hit, if it’s not a great record.

PCC:

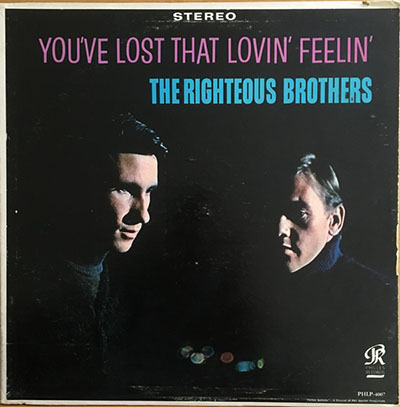

Certainly, “You’ve Lost That Lovin' Feelin’” is both a great song and a great record. It’s such an eloquent expression of love fading. Do you think that’s why people have related to it on such a deep level for so long?

WEIL:

You know, that song was the most played song of the 20th century and I think that everybody has gone through that.

PCC:

And what was the genesis of the song?

WEIL:

The genesis was that Phil [Spector] played this group for us called The Righteous Brothers and said “You know, you should write something for them.” And we went back to our hotel. We had come out to California to work with him. And Barry actually came up with the opening melodic line and the opening lyric line. And then I took it from there.

PCC:

And then once you have the jumping off point, does it usually come out in stream of consciousness? Or is it a painstaking process?

WEIL:

They’re all different. Some of them come like stream of consciousness and others are more thought out. They all vary. There’s no one way that things get done.

PCC:

And even with what you learned from the Leiber-Stoller experience, do you still agonize over each line, even each word?

WEIL:

Yeah. And that’s why sometimes when a singer will change a word [laughs], I’ve been notorious for being crazy when people change words. They once had Peabo Bryson fly back into New York to fix something, because he had changed a word. And, you know, I think about every word. And I make choices. All I ask is that the singer sing the words that are written.

PCC:

Well, one word can change the whole meaning.

WEIL:

Yes, absolutely. An “and” or a “but,” even something as ridiculous as that.

PCC:

You mentioned working with Phil, what did his production mean to your songs?

WEIL:

Well, it was always great to know that there was going to be a great production. And he was supremely talented… and supremely crazy. But he was a great, great producer. He had this vision in his head of what the record should sound like.

PCC:

From your perspective, from your experiences, what was he like to work with?

WEIL:

You know, he wasn’t easy, but we always had a good relationship with him. Of course, after “Lovin’ Feelin’,” we started to work on this song called “Soul and Inspiration.” And I felt that we were just rewriting “Lovin’ Feelin’.” And we played it for Bill Medley of The Righteous Brothers. Then we decided not to finish it. And Bill called us up after he had left Phil and said, “Remember that song you played for me? Could you finish that?” And we said, “Nah, you don’t want that song.” And he said, “Yes, I do!” [Laughs] And so, we did finish it and it was a great success. He made a great record. He made a Phil Spector record.

PCC:

It’s a fantastic record. With The Righteous Brothers, how did you feel the first time you heard their performance on something like “Lovin’ Feelin’”?

WEIL:

The first time we played it for them, Bill Medley said, “You know, that would be great for The Everly Brothers.” [Laughs] He eventually came around. I guess Phil talked him into it.

PCC:

You did a couple of really great Monkees songs — “Love Is Only Sleeping” and Shades of Gray.” Were those on assignment? Were you pitching through Don Kirshner?

WEIL:

We were pitching songs through Kirshner. You know, we didn’t write that much for The Monkees, because it was like the more commercial way to go. We weren’t into that. We were into more obscure songs that were not hits [laughs].

PCC:

But it was great, because those songs were more sophisticated lyrically than their earlier material. “Shades of Gray” was something thought-provoking for the group’s TV viewers to ponder.

WEIL:

Yeah, well, I’m glad you thought so. It was a little more sophisticated, you’re right, than a lot of the things they had done.

PCC:

And “Shape of Things to Come,” was that an assignment for the movie? [The rebellious 1968 cult classic “Wild in the Streets,” which starred Christopher Jones, Shelley Winters, Richard Pryor and Diane Varsi]

WEIL:

You know, Bob Thom, who wrote the movie, was a friend of ours, so we got involved from him. And I never dreamed that anything would be a hit out of that movie. Never. I’m glad I was wrong.

PCC:

In the mid-60s, a lot of bands were writing about drugs in a way that made them seem cool, but then “Kicks” went against the grain. An anti-drug song, yet it had an edge, especially the way The Raiders delivered it. Were you worried about any sort of backlash? Or was it a just a matter of having a sense of responsibility, wanting to say something on the subject?

WEIL:

Well, we really wrote it for a friend of ours. We actually wrote it for Gerry Goffin, who was getting very deeply involved in drugs at the time. And we thought maybe he’d listen to a song, rather than a lecture.

PCC:

Did he? Did it have an impact on him?

WEIL:

I don’t think so.

PCC:

But it must have been gratifying to have a song that had such a strong message and yet was such a commercial hit.

WEIL:

Yeah, it was, because it was against the popular culture at the time.

PCC:

And then The Raiders’ “Hungry,” where did the concept for that come from?

WEIL:

I don’t remember, to tell you the truth. But we had this show that we did in New York [the revue “They Wrote That? The Songs of Mann & Weil”], about 10, 15 years ago. Forgive me, it’s hard to remember how long ago things were [laughs]. And we did “Hungry” and we did it in terms of a McDonald’s commercial.

PCC:

That revue, is there any chance it will ever be released on DVD? Was it filmed?

WEIL:

No, it was never filmed. They wouldn’t allow it to be filmed.

PCC:

Any chance it could be revived in any form?

WEIL:

No, because we would have to do it. I don’t have the energy anymore.

PCC:

Did you notice your lyric-writing style evolving, growing over the years?

WEIL:

I never thought about it that way. I never thought, “Am I evolving?” I think I started out wanting to write for theatre, so I kind of stayed in that bag and then got a little more commercial.

PCC:

In the late 60s, early 70s, there were many pessimistic songs being written. You had hits with more optimistic numbers like “Make You Own Kind of Music” and “New World Coming.” Were those conscious efforts to put out something uplifting?

WEIL:

No, they weren’t conscious efforts. “New World Coming,” the best record of that is Nina Simone. Have you heard that? It’s great.

PCC:

Yeah, slower, bluesier, more soulful than the upbeat Mama Cass hit. Very different.

WEIL:

Yes.

PCC:

Even when you were writing all these hits, did you still study all the other successful records out there, to analyze what made them work?

WEIL:

Sure, we did. We were always conscious of what was out there, what was happening and what wasn’t happening. But not anymore.

PCC:

Not anymore because what is out there now isn’t necessarily what you’d want to be doing anyway?

WEIL:

Yeah, It’s not necessarily what we want to do and I don’t understand a lot of it. And I’m not a great fan of rap. I just think some of the rhymes are crazy and I don’t get it.

PCC:

Do you view the 60s and 70s as the golden era for pop?

WEIL:

Well, you know, I hate to be one of these old farts who thinks that their time was the best time, but there were a lot of great songs out there at that time, whether it was us or somebody else. It was just a very fertile time for writing.

PCC:

1986’s “Somewhere Out There” is such a beautiful song. It works in so many contexts. Was that tailored for the film [“An American Tail”], the story and the character?

WEIL:

Yeah, we read the script and the song in that slot was called “The Mouse in the Moon.” And I said, when we met with Steven Spielberg and his team, I said, “Do we have to use that title?” And he said, “No.” So we wrote “Somewhere Out There.” I never thought it would be a hit, because it was like a 1940s song. It was like “Somewhere Over The Rainbow” or something.

PCC:

It’s a gorgeous song, beautiful lyrics. You’ve had such amazing voices singing your lyrics over the years — Linda Ronstadt, Dusty Springfield, Gene Pitney, The Everly Brothers, Elvis, to name a few — were there any that were particularly surprising to you or that brought out more than you had envisioned in a song?

WEIL:

I think that James Ingram always made a lyric better than it was.

PCC:

Is there any lyric that you feel was more personal that the others?

WEIL:

More personal… you know, I don’t know. I wish I could give you a great answer to that… I’m trying to think… I honestly don’t know if there was any that was more personal.

PCC:

Was there ever an instance when you were writing and paused to think, “Is this too personal? Do I really want to put this out there in a song?”

WEIL:

I don’t think so. I never hesitated to combine our personal lives and our writing lives.

PCC:

So songs tended to come from personal experience?

WEIL:

Well, some did. Some came from personal experience. And “Here You Come Again” was written for a friend of mine who was going through that kind of experience. I remember she was from the south and Dolly Parton sang the song on some TV show and my friend said, [in a southern drawl] “Dolly’s singin’ mah song!”

PCC:

Were you thinking in terms of lyrics being able to stand on their own, like poetry?

WEIL:

No, I think lyrics and poetry are two different animals. Lyrics belong with melodies. And poetry stands by itself.

PCC:

What’s the song or the lyric that you’re most proud of?

WEIL:

I think probably “Just Once” [from Quincy Jones’ 1981 album “The Dude,” featuring James Ingram’s vocal], because I think it’s the most original idea ever written. Almost every other song you can say, “Gee, there’s another one that was like, I don’t love you and you love me and what can we do about it?” That one was something that I think had never been written before. [about a couple, inexorably drawn to one another, over and over again, but never able to make the magic work in a lasting way].

PCC:

So how did that come to you?

WEIL:

I don’t know. It came because Barry left me a melody and he went to a basketball game [laughs]. And I thought, “I’d better have something by the time he gets back!”

PCC:

And that’s just what drifted into your mind?

WEIL:

Yes, I just heard it with the melody.

PCC:

Did you find that songwriting could help you through a troubled time, be cathartic, or help you sift through emotional landscapes?

WEIL:

I never thought of it that way.

PCC:

Did you think of it at any point as just a job? Or was it always more of a passion?

WEIL:

It was combination. It was a passion. And it was a job. [Laughs] I think more a passion than a job.

PCC:

And are you surprised that the work has stood the test of time so well, that

these songs still move people just as much, decades after you wrote them?

WEIL:

I am constantly shocked by that, because I really thought that what we did would have its little life on the radio and then be over.

PCC:

Are you working on something now?

WEIL:

Yeah, we’re actually working on a television show that takes place back in the 60s, with a different kind of protagonist. We’re working with the writers. We’re executive producing.

PCC:

Is it related to the music business?

WEIL:

Yeah, it is.

PCC:

And will it have original songs?

WEIL:

Well, it can have old songs or original songs. It would depend on what comes up in the pilot.

PCC:

That sounds like an exciting project. Are you also still hoping maybe to write a Broadway show?

WEIL:

I don’t know if I have the stamina for it anymore. They really knock the hell out of you [laughs].

PCC:

The songs from the “Mask” project [a musical based on the Cher dramatic film; it never reached Broadway], might they be released in some form?

WEIL:

I don’t think so. I think that’s a dead project. I loved it when we did it, but looking back, I think we needed a stronger book, as did the book writer, and a different director, as did the director, eventually [laughs].

PCC:

And what about an autobiography? Is that maybe down the line?

WEIL:

No, I’m too private for that. I can’t reveal my life like that. It’s not something I really want to do.

PCC:

You’re more comfortable revealing yourself through song?

WEIL:

Yeah, absolutely… or through a novel with made up characters.

PCC:

Are there other great passions outside of writing?

WEIL:

You know, Barry’s a fantastic photographer. I’m a one-trick pony. It’s either writing or nothing.

PCC:

What would you like your legacy to be?

WEIL:

I’d like to know that these songs touched people, moved them and made them think about their lives.

For more on this artist, visit www.mann-weil.com or www.806Novel.com.

|