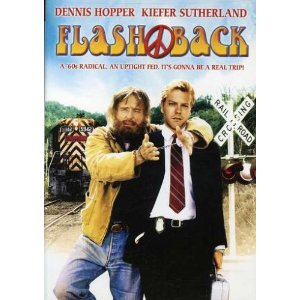

DENNIS HOPPER: A MAVERICK FLASHES BACK

By Paul Freeman [1990 Interview] He was the maverick. The rebel. The wild card. The bad boy. Most of all, Dennis Hopper was a dedicated, daring actor and an inventive, influential director. Coming out of New York’s famed Actors Studio, the Kansas-born Hopper had roles in two James Dean films, “Rebel Without A Cause” and “Giant.” He had guest shots in many top TV series, including “Cheyenne,” “Gunsmoke,” “The Defenders,” “The Big Valley” and “Combat!” His own rebelliousness nearly sabotaged his career. But he managed to get back on track and appeared in such pictures as “Cool Hand Luke,” “Hang ‘Em High” and “True Grit.” Directing and co-starring in 1969’s ‘Easy Rider,” he helped open the doors for a generation of indie filmmakers. His next directorial effort, “The Last Movie,” pleased neither critics nor the public, though it won the Venice Film Festival. 1980’s “Out of the Blue” earned critical acclaim. His directorial career hit another high note with 1988’s “Colors,” which starred Sean Penn and Robert Duvall. Hopper gave memorable performances in numerous films, including “Apocalypse Now,” “Rumble Fish,” “Blue Velvet” and “Hoosiers” (for which he received an Oscar nomination). He survived a chaotic personal life to create an important legacy in film. I had the pleasure of talking with Hopper while he was promoting his 1990 film, “Flashback,” co-starring Kiefer Sutherland. It’s about a ‘60s radical being brought to “justice” by a young F.B.I. agent. At the time of the interview, Hopper was already clean and sober and, as always, frank and funny. POP CULTURE CLASSICS: DENNIS HOPPER: About three years later, she came to me and said they’re ready to make this movie. So I went to my agency, CAA, and said, ‘Would you put me up for this part?’ They said, ‘Yeah, we’ll put you up for it, but don’t be disappointed, because you’re not going to get it. We’ve got Chevy Chase, Dan Aykroyd and Bill Murray up for this part. And we’re obviously pushing them, not you.’ I said, ‘Fine.’ And so when Marvin Worth offered me the part, I was really surprised. I ad-libbed a couple things, like ‘Rust Never Sleeps,’ was one of my one-liners, for Neil. I threw a couple of those in. But as for things referring to me, I’m not even sure ‘rebel without a pause’ was not in the original script. I think those lines were probably already in the script. PCC: HOPPER: Marvin’s a remarkable guy. He was Lenny Bruce’s manager. And he did ‘Lenny’ with Dustin Hoffman. He did ‘The Rose’ with Bette Midler. There was a Richard Pryor movie, too. He’s a good guy. I was moved by the film, which surprised me. I always thought the film was soft on the ‘60s. I had problems with the script. I didn’t think there was enough about the war, enough about civil rights, enough about free speech movement, things I was involved in, Haight-Ashbury, the love-ins, just all the things that I experienced. But they were really there in the film, whether it was in a photograph or something on the wall or a piece of a song. I wasn’t so sure it was going to be a good movie. Then when I saw it, when it got to the commune and got into the Jefferson Airplane song and Carol Kane and myself, I started getting moved. And I’m pretty cold about what’s happened before. And there’s plenty about the ‘60s. If you want to know about the ‘60s, it’s there. It wasn’t hitting you over the head, wasn’t preachy, wasn’t just a buddy movie. I left the theater feeling good, feeling everything was okay. And what it said about now was enough. The music was great, Dylan, The Stones. It was a nice piece. I’m glad I didn’t direct this movie, because I would have probably hit a lot of things on the head with a hammer, feeling people might not get it otherwise. PCC: HOPPER: PCC: HOPPER: But their programming, their work ethics, as far as doing the work, like nobody’s more professional than Sean Penn. He’s a professional actor through and through. He and Duvall both, who have these bad boy, bad men, whatever Duvall is, things about them, are really wonderful. You just give them their space and let them work. When I directed ‘Colors,’ I never had to go back and do a retake on anything because they had flubbed a line. That is unheard of in motion pictures, because we’re so undisciplined in our area of work, because you can do it over and over. But they were just so prepared. And they never went into their dressing rooms to rehearse with each other. They came on the sets and did these scenes and they would blow me away. And Kiefer’s the same way. Jodie’s the same way. They’re just really professional people. Given that they have a system where they’re allowed to work. They’re not given line readings. They’re not told when to pick a glass up and when to put it down, when to turn this way, when to walk out of the room and when to come back in, which is the kind of system that I grew up in, that I had to rebel against and say, ‘Hey, I have to have my space here. Don’t give me line readings. Don’t tell me when to pick up the glass.’ And they went, ‘Who do you think’s directing this movie?!’ It wasn’t a question of me wanting to direct a movie, it was a question of me wanting to be allowed to do simple things as an actor. But they are really professional people. It was a pleasure working with them. Sean Penn is responsible for me directing again. I owe Sean a lot. That’s because Sean is of the character and of the mind that he finds something poetic in losers. And he was very drawn to Charles Bukowski. And a lot of people like myself, and so on, that Sean feels are really talented and geniuses and wants to help them. And thank God. PCC: HOPPER: PCC: HOPPER:

PCC: HOPPER: There were things that you were forced to do. Like I did more Oskar Werner voices, translating his movies at Warner Brothers into English. I became his English voice. And I hated that as a kid. But I learned how to dub movies, how to loop movies, really well. You just don’t get that kind of training, unless you can go to a university. And at the time when I was growing up, there were no universities teaching filmmaking. So we had no access to that. So, with the studio system, if you wanted to learn how to make movies, you could. As much as you wanted to learn, you were allowed to do there. It was a great thing. Also, it gave you the opportunity of having a steady income. An actor never has a steady income. So for 40 weeks a year, you had a salary. Every year, you were picked up as an option, the same way you would be on a television series. But you didn’t have to do a television series. Today, to have that kind of security, you have to do a television series. And coming out of that to really get back into films is a long step. You may be secure for the rest of your life financially, but you’ve destroyed any possibility of ever being considered a serious actor... usually. Occasionally people come out of there. Like Steve McQueen came out of it and so on. But it’s rare. PCC: HOPPER: And live television was wonderful. ‘Studio One’ I did with Frankenheimer [1958 episode, ‘The Last Summer’]. And with George Roy Hill, Natalie and I starred in an hour-and-a-half ‘Kaiser Aluminum’ [1956 episode titled ‘Carnival’], live from New York. Those live shows, ‘Playhouse 90’ and those, they were great shows, great to do. But I love films. It’s wonderful to work in films. PCC: HOPPER: PCC: HOPPER: PCC: HOPPER: ‘Rebel Without A Cause,’ maybe it’s that part. That picture seems to hold up. It seems to still be the universal rebel, family rebel. The misunderstanding of the family, that age when you’re suffocated by your family and have to get out. Backus [character actor Jim Backus, portraying the henpecked father], in the apron, seems to be a little more poignant now than it was when it first came out. That film seems to be really, really strong. Surprisingly strong. Better that what I remember when I first saw it. I wasn’t sure about it when I first saw it. But I’ve it recently. I think it’s an incredible movie. But James Dean, as a person, he had more imagination than I’ve ever seen any actor have. There’d be a simple scene, like he was being searched. It was just written that he was searched. And he’d suddenly start laughing, because he was being tickled. Or when he gets up and starts howling, like the sirens, ‘Rowwwwwrrrrrr!’ All that stuff was just free stuff that was just coming out of him. At the time, 1955, I’m looking at this, saying, ‘What the f--k?’ Everyone else is saying their lines, ‘Hello. How are you?’ And here’s this guy standing up, screaming like a fire engine. Laying down, playing with a little monkey, like drunk. I’m going, ‘Wow, man where’s this stuff coming from? It’s not written on the page.’ I’ve only seen three males in my life, who had this kind of magnetism. And I’m going back to sort of the ape theory, that there’s the apes and they all go, ‘Ooh, ooh, ooh, ooh.’ And they leave the room and none of the female apes follow. But then there’s this one ape, that’s been sitting over there, gets up and leaves. And all the females and all the males follow them. And that’s like, there were three guys, when they were young. One was James Dean, would come into a room, even though he was not a star, he was a star only in Hollywood and New York, because he never had a picture that was successful until after he was dead. ‘East of Eden’ was a bomb and ‘Rebel Without A Cause’ and ‘Giant’ weren’t released until after he was dead. So he would come into a room and half the party would leave with him. Marlon Brando would come into a room, half the party would leave with him. Bob Dylan would come into a room, half the party would leave with him. I never saw it with anybody else. I didn’t see it with Elvis. Elvis was a curiosity they’d watch walk through the room. It was those three guys. Whatever that is, that’s why. I call it genius. Dean wasn’t necessarily a good-looking guy. First time I saw him, he had these thick glasses on. He could barely see. He used to say that one of the big reasons he could act so well was that he couldn’t see like four feet in front of him when he took his glasses off. He wore like Coke bottles. His hair was always messed up. He was always unshaven. He always had a big, turtleneck sweater on. Physically, he was sort of strange-looking. So it wasn’t that. It was whatever it was. Dylan is not... You’ve seen Dylan, right? So I don’t know. PCC: HOPPER: We’re talking about a lot of money, because the script is very complicated. I mean, I made ‘Easy Rider’ for $340,000. And this is easily like a $20 million picture. It’s after a nuclear holocaust. And it’s a lot of sci-fi. And there’s thousands of bike wars. It’s ‘Mad Max’ on a gigantic scale. It can’t just be schlocked through. It’s really an epic kind of a number. It’s two guys going across an isolated land. Searching. We start in biker’s heaven and there’s a nuclear holocaust and the maybe-Nicholson character comes back to biker’s heaven and says, ‘God, it’s terrible. There’s been a nuclear holocaust. The United States has won the war, but, God, they’re really in bad shape down there. They’ve got no leader. They’ve got no colors. They’ve got no flags. We’ve got to go down there, somebody’s got to become the President, get them back to together.’ They all volunteer, ‘We’ll go down!’ And he says, ‘No, no. There’s two guys down there, on a lonely road, in a ditch, they never got to biker’s heaven. Those are the guys, Captain America and Bucky, we’ll get them. So he goes down, on a silver Harley, brings us back to life. ‘Let me get those motherf--kers, where are they?’ And he gets us new bikes and a new flag, a ‘Don’t Tread On Me’ flag. He says, ‘Now go find a President and give him the flag, give him his colors back and restore the country.’ So we go out on this mythical trail, through these nomads, bike gangs of like The Kamikazes, the Japanese bike gang; the Taco Benders, Mexican bike gang; The Black Nationalist Bike Gang. And we look for a President. And then, at the end, we all converge on Washington, desolate, No Man’s Land, in front of the Lincoln Memorial. And thousands of bikers are fighting each other, trying to get this flag, which they think holds a magical power. The ‘Don’t Tread On Me’ flag. So ‘Easy Rider: Biker Heaven’ or ‘Easy Rider 2,’ whatever it would be, I don’t care if it’s made. If the money comes, great. If not, that’s fine, too. You don’t count on anything until it’s a go-project... and even then... [Laughs]. PCC: HOPPER: So when you talk about Hollywood dealing with sex on any level, they’ll say, ‘Oh, yeah, you can deal with it, as long as it’s taking place in the ‘60s or something, before the AIDS virus. But then they only want to deal with it in a way they think the ‘90s now can allow them to show, morally. Because the younger don’t relate to that aspect, they feel, of our time. PCC: It’s a good one, ‘Hot Spot,’ with Don Johnson, Virginia Madsen, Jennifer Connelly. It’s an amoral drifter who comes into a small town in Texas and starts selling cars in a car lot and starts having an affair with the car lot owner’s wife, Virginia Madsen, and the 19-year-old accountant, Jennifer Connelly, and finds out that all the guys who work in the bank are in the volunteer fire department and their video security system doesn’t work. He figures he might as well rob the bank. It’s a film noir with a happy ending. A happy ending, because, to me, everyone ends up with who they’re supposed to be with. PCC: HOPPER: PCC: HOPPER: PCC: HOPPER: Making movies, especially if you’re directing, you’re constantly fighting the clock. There’s so much to shoot every day. I can’t smile and take a moment to say, ‘Oh, it’s a wonderful day.’ My foot’s on fire. I’ve got four shots to get before four o’clock, folks.’ You’re getting three or four hours sleep a night and that’s it. PCC: HOPPER: PCC: HOPPER: Besides, I love acting. That’s what I do. It’s just a different trip. I like to say acting’s easy, compared to directing. I’m not sure that that’s true. Directing is much more time-consuming, because you don’t have any time to ever be alone. You’re constantly working. And you have the full responsibility of everything. Acting, you just the responsibility of your role, which is a responsibility of a different kind. But yes, I do think acting is satisfying, certainly. The ideal world would be to direct in a movie, then to act in one. Direct a movie, then act in one. If I could work that way, that would be the way to go. I’d love to do that. And every once in a while, direct and act in a movie. PCC: HOPPER: No, I don’t look at box office at all. I just hope I can keep working and I won’t have to look back. Maybe you never need a hit. Just keep working. |