|

The Singer-Songwriter-Guitarist Talks About His Adventures with Rick Nelson; Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young; and Every Mother's Son, as well his new album, "Founding Fathers" By Paul Freeman [2022 Interview]

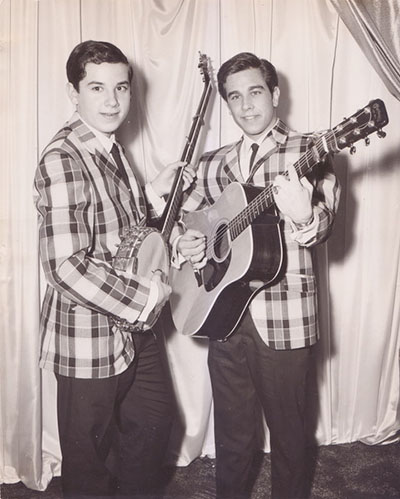

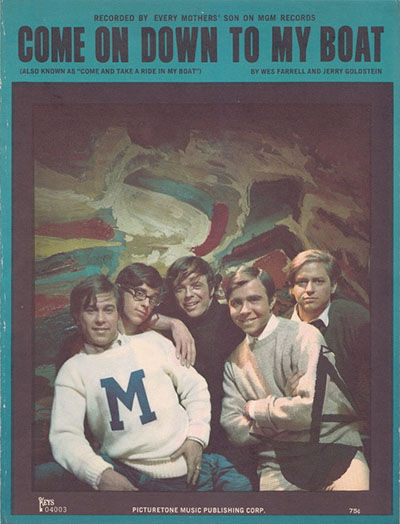

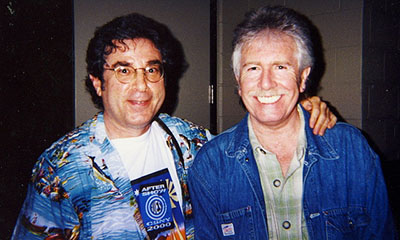

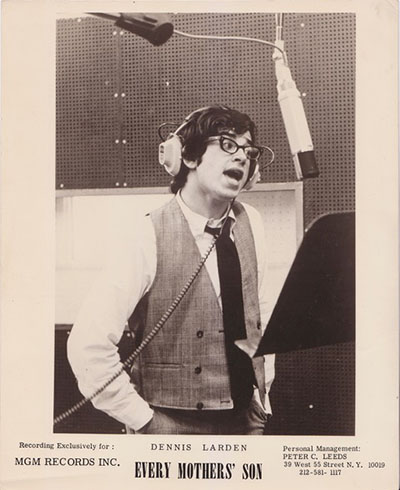

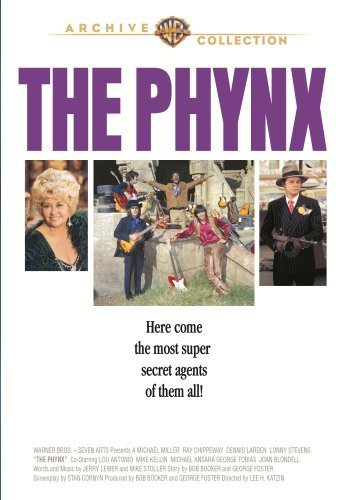

It all began when he and his brother Larry performed in Greenwich Village clubs as a folk duo. In 1966, they went electric and expanded to a quintet format. They called the band Every Mother's Son. Sarokin took the stage monicker Dennis Larden, the surname combining half of his first name and half of his brother's. Wes Farrell, a songwriter/producer with a Midas touch, took the band under his wing. Farrell co-wrote the Jay and the Americans smashes "Come A Little Bit Closer" and "Let's Lock The Door," as well as the song "Boys," recorded by The Shirelles and The Beatles. He later co-wrote and produced The Partridge Family hits. With Jerry Goldstein, he co-wrote the song "Come On Down to My Boat." Every Mother's Son's cheery rendition of the catchy tune drove it to #6 on The Billboard Hot 100 chart in 1967. They showcased their sunshine pop-rock on two albums, which mostly featured their original material. But they never duplicated the chart success of that first single. Larden went on to star in a disastrous rock 'n' roll comedy movie, "The Phynx." The frantic farce featured cameos by a cavalcade of stars who had been popular decades earlier. The great songwriting/producing team of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller penned the tunes for the film. They had written such classics as "Hound Dog," "Kansas City" and "Jailhouse Rock." Barely released in 1970, "The Phynx" eventually became a cult item. In 1973, Larden found a far better avenue to display his performing and songwriting gifts. He assembled a new incarnation of Rick Nelson's Stone Canyon Band. He was a key contributor to Nelson's little known gem, "Windfall." That 1974 album included such entrancing Larden songs as "Legacy," "Don't Leave Me Here" and "One Night Stand," as well the exhilarating title track, "Windfall," which he co-wrote with Nelson. The album, with its stirring harmonies and irresistible songs, should have been viewed as a country-folk-rock triumph. Instead it was largely ignored. Larden penned two more engaging numbers -- "Wings" and "One X One" -- for Nelson's 1977 album "Intakes." By the following year, Larden and Nelson had parted ways. Now he's again known as Denny Sarokin. He wrote the memorable Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young number "Sanibel." His songs have been featured on movie and TV soundtracks. Living in Nashville, Sarokin is a guitar instructor/song consultant who specializes in teaching writing and performance techniques for songwriters. He issued a best-selling DVD, "LICK*TIONARY - The Songwriter's Guide to Great Guitar." His E-book, "Songwriting in 3D" is currently available. Sarokin has recently released his latest solo album, "Founding Fathers: Songs of Life, Love & Spirit." It's a winning collection of uplifting, thought-provoking original material. He handled all of the vocals and instrumentation himself.

POP CULTURE CLASSICS: DENNY SAROKIN: I'm one of those guys, it comes through me. The muse just pops something into my mind or literally sings the melody to me. The tough part is figuring out where you go from there with the song. But I just get this little burst of intellectual or emotional energy. That's where the song seems to come from. And then it's just a little bit of the poet in me, a little bit of the preacher in me, a little bit of the concerned citizen. Am I going to leave this place a little better than when I found it? PCC: SAROKIN: There's always been a balance, a yin and yang, between conservatism and liberalism. But things have gotten so out of hand over the past few years. I just really felt compelled to use that as vehicle and say, "Hey, how do I make this apply to what's going on today?" And I'm getting a tremendous reaction, when people hear it. I'm not saying that in an egotistical way. The beauty of the way the song came out is, it doesn't give any answers. It just asks the right questions. The Founding Fathers, minds like that don't come around often, just select generations where these people just kind of appear on the Earth, like-minded people. There just seems to be a universality with the song, which I was trying to get. I thought we needed something that showed us the strength of the original concept, the Great Experiment and how we've strayed from it. And it's posing the question of how we get back on that path. So if you had an audience half full of MAGA hat people and half full of super liberal people, they're all going to say, "Oh, yeah. That's my song." It just instinctively worked that way. I was in L.A., doing a small club gig, like a mini, unofficial album release party. It was at a bar in Northridge. It was not a hip, cool, show business place. It was more leaning towards biker, hard hat, working guys. And I did the song. Then I played a little guitar solo, with a Chet Atkins style, "My Country Tis of Thee." And I when I finished the solo and was going back into the bridge again, all of a sudden, people burst out in applause. That surprised the hell out of me. Then I had people coming over to me, younger people, people who were vets and people who were bikers and the song just really hit them. And that's a home run to me. When a song reaches out and touches somebody, that's like a ministry to me. I really feel like I'm serving a higher purpose. PCC: SAROKIN: I had sort of arranged it and arranged what Tom was going to be doing. But I arranged it around the techniques that he did so magnificently -- the chimes and these little finger-chord syncopations. I kind orchestrated a bunch of the stuff that he'd done. But then there's times on Tom's parts where I'd just say, "Release The Kraken" and just let him do the magnificent stuff that he did. The song was just a pleasure to do with Rick. His voice really hit it well. He philosophically was very into it. Me and Jay DeWitt White [Stone Canyon Band bassist] were the background singers. We were really good at nailing parts. We just had a good sound together. Jay had this beautiful high vibrato. It was almost like he had that Don Henley thing and I had that Glenn Frey thing. We just sandwiched in nicely with Rick's rich baritone voice. PCC: SAROKIN: PCC: SAROKIN: PCC: SAROKIN: And he said, "Do you play slide guitar?" I said, "Yeah." "Well, my kid wants to learn slide guitar. Can you show him some stuff?" I said, "Yeah, I can show him some stuff." "Okay, I'll drop him off tomorrow. Where do you live?" So he came over to drop his kid off. He said, "I'm going over to Graham Nash's house. Got any songs?" He was like Graham Nash's best friend. They were like best man at each other's weddings. "Yeah, I've got a few songs." And like a day later I get a message on m answering machine saying, [in a British accent] "Hello, this is Graham Nash calling. We're all going to get rich on your song, 'The Isle of Sanibel,' buh-buh-buh-buh." I got real excited. Then I didn't hear from him for a while. I called Allan and he said, "Oh, no, Graham loves the song. He's really into it." Okay, fine. Then a little while later, I get a call from their manager, who says, "Yeah, Graham wants the song." I said, "Okay, great, are they recording?" "No, they're not recording." "Well, what is he going to do with the song?" "Oh, he just wants the song." I said, "Okay, you let me know when you've got something happening." And I got a call a few years later saying, "Yeah, we want to do your song." They never got back to me. A couple years later, "Yeah, Graham's got this special project. I can't tell you about it, but it's a special, secret project. He wants the song." I said, "You don't get it -- you're supposed to be telling me that Graham and like Elvis and John Lennon's ghosts are doing this project. Just call me, when you've got something to tell me, like 'We're going into the studio to cut it' or 'He's going to be producing this artist and...' Something! Then I'd be happy to talk to you." So I just kept my publishing. If initially, they had told me, 18 years earlier, "We're going into the studio this week and we want to cut your song. We want publishing," at that time, I would have said, "You got it." It's going to ship gold, platinum. Then I ran into Graham out here in Nashville at a songwriting festival, "Oh yeah, yeah, we want to do the song... " I got a call like maybe 15 years down the road, I was working on a script, on sort of a little musical hiatus. "Hello, this is Graham Nash. Is Denny there?" "Speaking." "Who plays guitar on your demo for 'Sanibel'?" "Well, I played guitar. I played and sang everything." "Oh, could you get down here right away? We had James Taylor; he couldn't cut the guitar part." Wow, can I have a copy of James Taylor doing anything on one of my songs? [Laughs] It's like, I'll make a little shrine with apples and incense and bow every morning. And like a half-hour later, I'm in the studio with Crosby, Stills and Nash cutting the song. And originally, it was kind of like "Blackbird" or something, where the song is really based around the guitar parts. And so I laid that down. That was one of the greatest days of my life... and one of the worst experiences I've ever had in my life. PCC: SAROKIN: PCC:

SAROKIN: So I'm sitting down doing that with him, on a stool, at the piano, and Crosby and Graham come over and Graham starts singing the melody. And then Stills wanders over to the piano and it's kind of like one of those old Merv Griffin shows, where you're all sitting around the piano and guys are singing. And they're hitting the bridge and they just hit that magic. And I went, "Oh, this is the most thrilling moment of my life, let alone career." And that lasted maybe eight seconds. And then Stills stops the singing, starts the talking. He says, "Let me try doing this song. Maybe I should be singing this song." Graham says, "Well, Stephen, this is one of my songs for the album." Stephen says, "You don't need... Fuck it. I'll just leave the band." And without a beat, I said, "I wouldn't do that, if I were you, Stephen." And everybody just flashes me the dagger eyes. Like, "Wait a minute. He's an asshole, but he's our asshole. You're out of line." And I curled my eyebrows up and said, "They won't even have to change the logo." And everybody kind of went, "What the hell does that mean?" And one by one, it kind of clicked, "Oh, Crosby, Sarokin and Nash." Then they got a big laugh out of it. Even Stills went, "Yeah, ha ha ha." And then they didn't have it on an album. They never sent me any paperwork. And then I finally get a call, I'm in Nashville, about 18 years have gone by, I get a call from Graham. "Look, we're doing the song. Neil's coming in for the album. He loves the song. But he wanted to do a part of it. He wants to sing a verse on it. And we lost the masters. So I just had the little cassette that I took home." I said, "Why didn't you just call me? We could have recut the master. We did the song in under two hours, including all the guitar overdubs." "Oh, no, there was something about that cassette that was magical." Okay, whatever. So they spent like a week or two weeks in the studio with Pro Tools, trying to get Graham's voice out and putting Neil's in, where one plane ticket and a two-hour session later and it would have been as good or better than before. By that point, it has been so long. And they assumed I was holding out on them, as opposed to they weren't offering me anything, not in terms of money, they weren't offering me anything to do with the song. Then finally, "We'll give you this much. We're putting this money on the table, up front, no advance. Boom. Just yours, in your pocket." And he wanted half the publishing on their version only. If somebody else did it, it was 100 percent mine, writer and publishing. It was a great deal. PCC: SAROKIN: And the album ["Looking Forward"], I was underwhelmed. I listened to the whole album, I didn't go right to my cut. And I was kind of underwhelmed, I mean compared to "CSN" or "Deja Vu" or whatever. A reviewer said, "Let's break this up by each writer." And they talked about each person's songs and then, the last paragraph of the review was, "Oddly enough, the last song, was this little fanciful desert island fantasy. It was a cover, written by this guy Denny Sarokin. Oddly enough, it was the only song on the album that sounded like a Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young song." Well, God bless us all. PCC: SAROKIN: But Crosby, it was, "David, this is Denny. He wrote 'Sanibel.' He's going to play the guitars.'" And David went, "Well, just make sure you do it like the demo, or you'll fuck it up." Nice to meet you, too. And Stills, I didn't have my guitar. It was in the shop. I told Graham and he said, "Hey, come down here, we'll go through Stephen's guitars. We'll pick out whatever you want, set it up, string it up." "Okay, great." So I go down there, I'm going through them with the roadie, pick this beautiful, pre-War B-28. They're restringing it. The roadie's on the phone, 'Uh, it's Stephen. He says if you fuck up his guitar, he's going to kill you." And it just went on and on like that. At one point, he's playing some odd, twangy, vibrato, bluesy thing over "Sanibel." He's not even playing in the right key half the time. He gets frustrated and walks out. I said, "Stephen, I can show you this part. It's just an open tuning. It's kind of like me ripping off you ripping off Joni Mitchell." He went [shouting] "I taught her everything she knew! She didn't know anything until then." The famous story is, when they were wheeling Crosby in for his liver transplant, Graham was leaning over him on the gurney, going as far as he could go with him, on the way to the operating room, and the last thing he said to David, as he was going under was, "Don't you leave me here with Stills." But I'm proud to have been associated with a piece of my heroes and their histories. It looks good on the bio. And a lot of people love the song and love their version of it and became familiar with me and my music through that. PCC: SAROKIN: But as for some of my early influences, Tim Rose was a big influence on me. The Big Three -- that's Cass Elliot, Jim Hendricks -- not to be confused with Jimi Hendrix -- Jim later wrote "Summer Rain," a big hit for Johnny Rivers -- and Tim Rose. Tim Rose was a real aggressive guitar player and had that nice, grainy, raspy, boozy voice. I loved The Big Three. I had met Mama Cass. And, of course, The Kingston Trio were the people to follow. I was into it all. I ran into Jim McGuinn. I had a great affinity for him as a session player, backing up The Chad Mitchell Trio and all the stuff he'd do on banjo and guitar. I was really into the guys who were playing the accompaniment to the song. Even in The Weavers. Seeger was phenomenal, but I really learned so much from Fred Hellerman. He's so supportive on the acoustic guitar. He just arranged the song so well. He'd put in a little signature lick. He just knew how to lay that song down, but have signature licks and little connective tissue things and moving bass lines going through it. I had met Richie Havens, which was one of those dreams and nightmares. I had just bought this Guild dreadnaught guitar, a real pro guitar, my first, and I had it, I was at Cafe Wha? [legendary Greenwich Village club]. Somebody said, "Hey, Richie Havens is here and he needs a guitar. He's going to do a set." I said, "Wow, give Richie Havens my guitar." And then I stood there, near the front row, and watched my guitar being turned into firewood. [Havens' incredibly vigorous playing style battered innumerable acoustic guitars.] I had this brand new guitar with all these scratches and scrapes and chunks taken out it. At least I learned a lesson well. Those were good days. You'd go down to Washington Square on Sundays. And every 25 feet, there was somebody else doing something. There were rank amateurs and wannabes doing, "Michael Row The Boat Ashore" and then there were these really super bluegrass people, super folk guys, pros just down there hanging out with each other. It really had that Paris in the 30s feeling, with jazz or the writers kind of feel to it. PCC: SAROKIN: And my brother was in college and there were college parties. He knew a guy who knew a guy and we put together a little band. It was like, "Be better than a garage band." But we weren't pro players. We'd just be playing fraternity parties and stuff like that. We did a couple of demos, but we didn't break through. Then we had a guy, Peter Leeds, who was sort of managing us as a duo. He contacted us and said, "I'm sharing office space with this guy Wes Farrell, who's a producer and a songwriter. And he's looking for bands." We went and auditioned. With the folk stuff and the rock stuff, I was sort of getting my sea legs a little bit for the song arrangements, a lot of vocal things. We did stuff like The Hollies' "Look Through Any Window." Frankie Laine's "Jezebel" -- I worked up a big folk-rock arrangement of that. We kind of jazzed up some other songs. And he kind of liked it. And we went, "Oh, okay, we're that good. We're the next Beatles." And Wes was actually one of those guys who was like, "I wrote the song. I'm the producer of the song. Give me some bodies, put them here and have them sing it and I'll release the record and have a hit." In fact, I found out from Rick Derringer [The McCoys], years and years later, that they were offered "Come On Down to My Boat, Baby" first and they turned it down. They thought it was too bubble-gummy. But they did "Sloopy," which was a Wes Farrell song. But they said, "No, no, we're off. We're a real rock 'n' roll band. Okay, we had a hit, cool. But we're going to go back up Johnny Winter." So we had that first big hit. And basically, we kind of wrote the rest of the two albums. So I started getting my studio chops and getting my writing chops. PCC:

SAROKIN: You just had your song and it's luck of the draw. And whether you stay in your same poppy formula, using the same producer. We were kind of evolving. The music was evolving. Drugs -- grass, LSD were coming through. We were changing the way we looked in clothes. I was evolving as a musician and I was really listening to The Beatles, the writers, hearing how they were changing. And listening to the guitar parts. What is George doing? And, okay, what are other guitar players doing? The process was really taking me over. I was learning about the studio, learning about being a guitar player, learning about needing a signature lick. I was going back to my Weavers roots and finding a combination of their big, strong folk harmonies and The Beach Boys' oohs and backgrounds, figuring how I could morph that into arrangements. So really I was sort of getting my college and Masters degree in recording and being a guitar player and being a songwriter. PCC: SAROKIN: PCC: SAROKIN: One day, we did one song that I didn't want to do. We had started to go back and pick up people's songs. He brought something in and I wasn't crazy about this song, called "No One Knows." And the producer came in the next day and said, "Hey, check this out." And he had a string section booked after we left, at like two in the morning. And it just sounded like orchestrated crap. And I had like my first music industry nervous breakdown. I had to get that over with. I jumped across the desk at him [chuckles]. After that, it was just nothing. He went on to The Cowsills ["Indian Lake"] and other things. The whole thing just sort of dissolved like cotton candy. There was no interest in us on the label. There was no interest in us with Wes. I had no interest in being with him. Nor did I have the sea legs to say, "Okay, I'm doing my own album." You didn't do that stuff in those days. So then I was doing nothing. And "The Phynx" came along. Again the manager, Peter Leeds, was in the same office building as the guys Booker and Foster [comedy writers Bob Booker and George Foster, renowned for the Grammy-winning satirical album "The First Family"]. They wrote "The Phynx" and produced it. They were like "Laugh-In" writers and Bob Hope writers. And they were looking for somebody. I met with them. I did a little audition, a musical audition. I had Hal Blaine on drums; Jerry Schiff, Elvis' bass player, he played bass; and Artie Butler played piano. Artie Butler was an arranger. He arranged one of my favorite arrangements -- "Solitary Man," the horns on there. But he was also the guy who played on "Feelin' Alright." I was big on Stephen Stills and "Love The One You're With," that whole thing. So I did a version of "Let's Get Together," the Youngbloods song. But I did it really like Mardi Gras tempo. I started off just strumming and then [imitating a dynamic drum sound] Hal Blaine was in there. "Oh, man, this is heaven!" And nobody even said,"Look, we'll call you and we'll let you know." It's just like, from that moment on, I was in on the project. And I said,"What the hell? I'll go to California and be in the movies." The movie was dreadful. There's a review where somebody called it the worst film ever made. There's a review that walks through, like you're watching the movie, scene by scene, explaining how awful it is. So that was supposed to be an enormous, like a Woodstock project. Somebody said, "Okay, The Beatles did their thing and the movie was a hit. The Monkees took The Beatles and did it on TV and had a hit. We're taking The Monkees and doing it in a movie and we'll have a big hit." And it was the last movie done by Warner Seven Arts. And they were bought out by Kinney, while we were wrapping it up. And Warner Kinney had just bought this little documentary called "Woodstock." So guess who got the promotion. That was fine with me. If I had made a lot of money out of if, that would have been cool. But if it's just a Trivia Pursuit type thing, that's fine with me. The thing that I remember most, that I loved about it, was I got to meet and hang with Leiber and Stoller. They were heroes. I think the music that they wrote for this was an assemblage of the most mediocre songs they'd ever written. But I got to hang with them and they were great guys. And I got some real inside stories. And I was the only guy in the band who was allowed to be in the sessions and play on the sessions. So I got to spend two weeks in the studio with The Wrecking Crew. It was Larry Knechtel, Mike Deasy, Jerry Scheff and Jim Gordon. I was just doing the reference vocals and the guitars. But my rhythm guitar parts ended up being in the stuff. So working with those guys, that was an experience where I just went, "Wow." PCC: SAROKIN: PCC: SAROKIN: PCC:

SAROKIN: PCC: SAROKIN: PCC: SAROKIN: So by default, I'm lead guitar player. Even in Every Mother's Son, I was lead guitar player by default, because I played a lot better than my brother did. I would say, "Okay, George Harrison's a lead guitar play. He comes up with a lick. I gotta come up with a lick." It's part of my job description. It's not like I'm a guitar virtuoso. So a gig came uo. That band, we were being supported by some pseudo-entrepreneur rich guy that had us playing in his garage up in the Hollywood Hills, paying us a little pittance to be a band. He thought he was going to be a manager, a big shot. That dissolved, as well, as soon as he stopped paying us. This gig came along at this place called Sewers of Paris. It was a transvestite club, in the alleys off of Hollywood Boulevard. You had to go down to a basement -- as sleazy as sleazy could get. And it was from two o'clock till the morning. And they couldn't afford to pay a full band, so we had to do it as a trio. That's where I really honed my chops. That's the time when Cream was happening. So I would be singing, playing live lead guitar, but not just the solos, I had to sing and throw in the guitar lines, while I'm singing, as well as in between voices. And that got my energy up and got me up more as a front man kind of thing. We were doing that for a little while and I came home one night and I was sitting with my lady and we were watching "The Tonight Show." And Rick Nelson came on with The Stone Canyon Band. And he had that [sings], "She's got everything she needs. She an artist. She don't look bad..." ["She Belongs to Me"], which Dylan said was his favorite cover of any song that anybody had ever done. So I turned to my lady and said, "That's what I should be doing." "You want to be Rick Nelson?" "No, I want to be the guy standing next to him, playing acoustic guitar and going [sings] "Da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da." We laughed. I went to the gig that night. Came home the next morning. One of my best friends, Lindy Goetz, who was working as a record promo man for MCA, and who later went on to discover and manage The Red Hot Chili Peppers, he called me and said, "Hey, call this guy Willy Nelson right away [not country music icon Willie Nelson, but Willy, Rick's cousin/manager]. Rick's band just quit and they've got these gigs coming up. They need somebody now." I called Ty [drummer Ty Grimes], who I'd been working with in this other band, and Jay DeWitt White -- I hadn't really met him at that time, but I went down to hear a friend of mine at a club and Jay was the bass player and the singer. And I went, "Wow, that guy's really solid. What a great voice!" And I just called him up and said, "We kind of met backstage. Want a gig? I got this gig. Get your ass down here." We auditioned. I'd heard the Rick at the Troubadour album. And I knew he was doing his contemporary versions of his old songs. Allen Kemp was his guitarist at the time, in the original Stone Canyon Band. And I was just listening to the leads and the parts he was playing and I went, "That's not something I have to duplicate." I mean, with something like "Garden Party," you want to nail the hit record. But the rest of it, it just sounded like garage band, jamming guys. You know, the record sounded great, all together. And Tom Brumley, adding to Rick's reinventing the songs, was kind of the birth of California country rock. But I thought, "I'm not going to sit here and just try to cop whatever Allen Kemp was playing." I was into Derek and the Dominos and stuff, so I had a little more souped-up version. At the first rehearsal, I knew Rick used to close with "Believe What You Say." I really souped it up, came up with a new intro and put the little intro tag at the end. And modulating. And I think I might have even played some slide guitar in it. We finished the song and Rick was all excited -- "Hey man, that sounds great!" And he turned to Tom Brumley -- "What do you think, Tom?" And Tom, sitting there quietly, goes, "What's wrong with the way we've been doing it?" I said, "Okay, [laughs] this is going to be an interesting experience." PCC:

SAROKIN: But it worked out okay. We started cutting the "Windfall" album relatively very quickly. And the fact that I had some songs coming out, I think he sort of got more into me as the songwriter and the arranger. And the vocal sound I was shaping on my end of the stage, with Rick in the middle, he felt it was cool. I always respected the steel guitar and liked it, if I was listening to something like "Together Again" [the Buck Owens hit, which featured Brumley], a great song and the instrumental stuff was terrific. Don Rich [of The Buckaroos], a great guitar player. He and Burton [James Burton, Rick Nelson's original lead guitarist in the 50s and early 60s] kind of invented that twangy Tele sound. But when we had songs like "One Night Stand" or "Legacy," [two Sarokin compositions on "Windfall], I would sort of work with Tom on his parts. He was kind of open to some ideas that I had, as the songwriter. PCC: SAROKIN: So he had one more album obligation with "Windfall." But they had something saying, "Well, this is your budget. And we're cutting you off at midnight on this Friday. You're all going to turn into pumpkins. And if you don't finish the album, if we don't have 10 finished cuts, we don't have to release it. You'll have broken your contractual obligation." Rick's manager, his cousin, Willy Nelson, was always panicked about this stuff and was like, "Denny, we've got to do this and blah-blah-blah." And Rick was always on like Rick Standard Time and just went about his thing in his way at his tempo. And we needed one more song. One more week in the studio. And I went to the house. "Do you have a song? "Yeah." "Will you play the song for me? What key's it in?" I would work it out on acoustic and play it for the band. So I was kind of like the uncredited producer/session leader/arranger/chief bottle washer, whatever. I went over there on a Friday morning and said, "Okay, before we go, play me that song." RIck goes, "Well, I..." "You don't have a song." "Well, I uh... " And I didn't even let him finish the sentence. His guitar case always had like tons of these little scraps of papers and matchbooks that he wrote little things down on. And I just started like a dog digging for a bone, just running through pieces of paper -- throw it aside, throw it aside. Then I finally saw one little matchbook that had on it, "If you've never heard these things, then love has flown on faceless wings, that's where love begins, within you. Have you ever heard the windfall, have you ever heard the leaves call." I said, "Okay, this is going to be the song." And as I was reading this, I felt that there was a little cadence to it. It just suggested something musically. And the Stone Canyon Band per se was not known for its lightning fast studio reflexes. We were not The Wrecking Crew. So I had to have something musically that basically we could do really quickly. And I've got to be the driving force. I've got to lay down the majority of it and just slip the other components in. So I knew I could do that kind of "Love The One You're With," a couple of big, strong, kickin'-ass acoustic guitar parts. I showed Jay a bass line. The drummer wasn't a big Latin guy, so I had him just play a boom-ba-boom, on the kick drum. And [percussionist] Milt Holland, the session guy who played on "Big Yellow Taxi" and stuff like that, I said, "Get him down here." And he's going to be like the Mardi Gras. So we arranged it for that. I played the melody for Rick and he said, "Oh, yeah. I like it. That would be cool." We had Milt in there and we couldn't even afford the time to have him do all the parts -- timbales, scratcher, maracas, all that stuff. So any time he'd add something on there, I'd just pick some other percussion part and do the overdub on it, too, just to cut the time in half. And I knew harmony-wise, me and Jay could nail it. In like half an hour, we'd have the master vocal down. And it's like Cinderella won. Five minutes to 12, we got the song finished and the album was in the can. I went through I think it was either 23 or 27 packs of cigarettes that day. PCC: SAROKIN: On "Easy to Be Free," he really felt that, too. The song "Last Time Around," all that reincarnation stuff was something he was questioning and believing in -- a beautiful song. He was a good writer who wrote some great songs and I think could have really become a much bigger writer, could have written more signature songs, if he had focused more on that. PCC: SAROKIN: He said, "Dad, I want to make a record." And anything the two brothers did, they brought into the show. Baseball -- they brought baseball to the show Whatever it was, they wrote it into the show. So Ozzie said, "Okay, we'll make a record and we'll have you like at the prom, singing that song. And the show aired on like a Friday. On like the Monday, ABC gets like tens of thousands of requests -- "Where do we buy this?" So Ozzie, being the smart guy that he was, goes, "Okay, every show ends up with Ricky sing a song." So he sort of got into that by being, in the nicest sense of the word, cocky. And he just had this little persona. He could close his eyes and do "Lonesome Town." He never tried to do the Elvis thing. And I don't think Ozzie would have let him. He just stood there like a stone, just had those big plump lips and that quiet thing -- the antithesis of the Elvis thing. And the gals loved it. Like Elvis was the king of rock 'n' roll and Rick was the crown prince. So I think he was just comfortable with his voice. And he loved the rockabilly. And when he got Burton and the original guys in his little backup band -- drummer, standup bass and Burton, he got really comfortable with that, fitting in, finding a cool song that he liked and dropping it into the components of that band. I don't think he ever thought of himself as a great singer or an inadequate singer. He just sang. And he'd been doing that for so long. He was allowed to do that, so "poof," he's a singer. PCC:

SAROKIN: PCC: SAROKIN: So he put that little shame thing into Rick. But Rick got it, like "Okay, I really owe this to the crew and consequently to the people who are buying my stuff, too." So after shows, he'd sit there like a little bobblehead Rick doll, when people came back, he would talk to them and sign autographs and stuff like that. He was always very courteous. In airports, he'd always stop and we're trying to drag him off, "Come on, we're going to miss the plane. You're late all the time anyhow. Come on, come on." So he was always appreciative of his audience and his fans. PCC: SAROKIN: The Eagles, Frey and Henley and Jackson Browne and all those people, were sitting there at the bar, trying to get people to buy drinks and trying to get laid, while Rick was doing the first country-rock project on stage at the Troubadour and recording it. But he just sort of never got that recognition. And you read all the stories of Henley and Frey and they had that, "We're gonna do it. We're gonna make it. We're gonna make this thing happen. Nothing's gonna stop us." The Lennon-McCartney stories that are told and that they tell -- "We always knew we had this. We're going to get this, no matter what anybody says. We're going to be the best." They had a drive. I never felt like Rick had the kind of drive. He knew he'd had so much success in various ways. He was so well known that just somebody sitting there in the airport, "Oh, Ricky!" Or a fan coming backstage and bringing an album for him to sign, where he had like a yellow V-neck sweater on, big, ruby red lips, and a pompadour, of course. "See? They love me, the fans," as opposed to going, "That's nice and God love every one of them. But we want their kids to be buying." When we signed with Epic -- it had been really hard to get anyone to pick us up -- when we finally got the deal with Epic, there are so many nightmare stories. I went with Rick to the 21 Club, where the president is saying, "Ladies and gentleman, to a man who is a star already, we're going to make him a superstar -- Rick Nelson!" And we're doing champagne toasts. And then we did an album and it just kind of lay there like a lox. When we got the record deal, it was a two-record deal where the second record is Epic's option. And I was the closest to Rick, in terms of the band. Tom was, in terms of being around and getting him on the plane and stuff. I was, in terms of the music, what's going on with the band. And for every session, I'd literally have to go to his house, drag him out an hour-and-a-half late, drive with him down to the studio, stay with him in the studio all day and all night, drive back. Rick was going through a divorce and money problems, blah-blah-blah-blah. I said, "Rick, this is what we should do. This is what the next album should be. You're coming home from these parties and these charities all the time, saying, "Hey man, Paul McCartney came up to me last night, singing, 'Hello Mary Lou, Goodbye Heart...'" "Oh, man, Lindsey Buckingham came over and said, 'I'd love to play guitar for you.'" And George Harrison was "Uncle" to Rick's kids, lived right up the street. Creedence Clearwater, Fogerty, had seen him and loved him. He recorded a cover of "Hello Mary Lou." And I said, "Rick, you're a songwriter. I'm a songwriter. You're a publisher. I co-publish my songs on your record. You write two of the best songs you've ever written in your life -- and maybe you're going to have to write 20 songs to do it -- you pick two of the best. I'll write two of the best songs of my life. Then you call Paul McCartney and say, 'Hey, Paul, I'm cutting an album. I was just wondering if you might have a song.' Paul McCartney would have a song for you within 24 hours. Ask him if he'd like to play some bass on it. He'd fly in from London to do it. I said, call up George. Call up Fogerty. Call up Lindsey Buckingham. Then we go to the record company and say, "We have two Beatles and the Creedence Clearwater guy and Fleetwood Mac guy and they're going to be writing songs and performing on Rick's new, debut Epic album." How crazy would those people have gone? And I said, "This is guaranteed. This is going to be a cash cow. And hey, bring in James Burton to play lead guitar. I'm the lead guitar player and I don't care. Let Lindsey Buckingham play. This would be a gas. And for me, it would be a thrill to work with these people." This would be something that would guarantee we got the second album. Okay, the second album, we could go back to our little Humpty-Dumpty writing songs, Stone Canyon Band, whatever it is. And Rick never really said anything and then totally dropped the idea. PCC: SAROKIN: The manager -- if you can call him a manager -- we were on a record promotional tour and we were in a Winnebago outside of some giant mall that just opened. And I don't remember, either it was 110 degrees outside or it was like 10 degrees outside and there was nothing anywhere around except this mall that was opening with clowns and balloons and free food and Rick Nelson doing a concert. I'd gone to all the record stores. There used to be Sam Goody's and Tower Records and stuff. And none of the people had ever heard of, let alone had our album. I went back to the Winnebago and the manager came in and said, "Hey Rick, it's like an all-time, this is the greatest, they said they'd never seen a crowd like this. It's the biggest crowd they've ever had." And Rick sort of smiles and turns to us and says, "Hey guys, did you hear that? Man, it's like we broke every record here. It's the biggest crowd they've ever had!" He was truly excited about this. And I said, "This is not a moment to be slapping ourselves on the back. Of course it's a big crowd. Everything is free. There's nothing else to do anywhere. It's the grand opening of a mall. Meanwhile we're on a record promotional tour. Nobody in any of the record stores has even heard of our records. Even if these people wanted to, they couldn't go buy our records. This is not the time to be congratulating ourselves. We're sinking on this promotional tour. It's going down." And then that turned to, "Ooh, Denny's got bad vibes." So I was just like the reality check guy. And I care about my songs. I said, "Hey, I've got two songs that are going down the tubes on this album. That's why I'm here. I like the band. I like the music. But that's sort of my purpose of being here." So that stuff just happened more and more. And I used to say, "Rick, get up in the morning..." He hated mornings. "Get up in the morning and call somebody. The manager should be doing it. Or I'll do it. Call ahead to whatever town we're going into, call the local radio station and we say, 'Would you like to have Rick Nelson come in and talk to your drive-time morning deejays, do a little interview with him about the good old days, play a couple of oldies, play a cut from the new album, say that they're going to be playing tonight at the Marquee Theatre? Come on down to see us.' And you're reaching tens of thousands of people." No. Never. Didn't want to get out of bed for it. So either there was a naiveté there or whatever. But I just couldn't push the boulder uphill any further than that. And there was zero support from the record company. But when I was there, I think especially on "Windfall," Rick was getting excited. He really felt there was, not a partnership, but a musical energy there. Even his songs were better on "Windfall" than, other than "Garden Party," a couple of his previous albums. Like I said, I really think he was getting confident in the path that I was laying down musically. The country, the rock and the ballad thing were coming together nicely. But it had a more contemporary thing to it. My favorite cut on "Windfall" was "Don't Leave Me Here" [another alluring Sarokin composition] And that was something where I had to go up to Tom and really tell him, "Tom, I have some ideas for the arrangement and stuff on this. And if this works out right, nobody's going to know you're on the steel guitar on this track. But everything you're going to be doing is going to be an integral part. You're going to be doing some of that chime thing walking up the stairs. I'm going to be doing that little Eric Clapton-y, George Harrison thing going down the stairs. And we're going to have the big lush harmonies. And he was good about giving that a try, sort of giving me a, "Well, Denny wrote the song. Let's see what he's going to do with it." PCC: SAROKIN: PCC:

SAROKIN: So he deserved a tremendous amount of credit for his personal A&R work, the songs he chose and the musicians, the tempos and the delivery of it. But it wasn't like a Ray Charles or somebody where you went, "Wow, that voice!" A lot of musicians loved the records. But again, it was that Burton thing that turned a lot of musicians on to it. Not that they didn't like the songs. I mean, I liked the songs, when I heard them. James Burton influenced me, but I never tried to sound like him, never imitated him, tonally or technique-wise. To this day, he's a wonderful, great character and a very incredibly influential guitar player. He put a set of banjo strings on his guitar. Where a G string on guitar is usually wound like an acoustic string and it's thicker, he put on these unwound strings, like a banjo string, so that he could really bend it [makes a twangy guitar sound]. That was a sort of unheard of thing until he did it. PCC: SAROKIN: PCC: SAROKIN: PCC: SAROKIN: James Guercio wanted to produce and manage Rick. [Guercio was a musician/songwriter who produced such bands as Chicago, The Buckinghams and Blood, Sweat & Tears. He managed several acts, including Chicago and The Beach Boys.] A lot of big names wanted to. But again, like when I wanted to do an album with all the stars on it, there was something about him feeling intimidated by somebody that big, like he might lose control or something. I don't know what his personal motivation was. He used to like having Ozzie, though Ozzie never managed him. But his original manager when I was there, Willy Nelson, would have done anything for Rick, would have taken a bullet for him. He was a great guy, worked hard. He didn't have the power that a big name guy would have. But he worked and sweated and chain-smoked... and protected Rick from everything. He'd even come to me, "Denny, this is going to be really fucked up, Denny. You gotta make sure this gets taken care of," because talking to Rick was like in one ear and out the other [laughs]. But this other manager just did shit like when we were cutting the Epic album, I was at the studio, driving out of the parking lot with Rick. He was dropping me off at my car at his house, at the end of a session. And the manager said, "Oh, we're working out a deal, We're going to pay like $4,000 and you guys are going to split it four ways, for doing the album. And I went, "Well, what's that all about? A, it's going through a union. And B, any session has to have a leader on it, even if it's just one person in the room and that one musician in the room is the leader, getting double scale. And all I'm asking is, when I'm in there playing guitar, doing vocals, I'm the leader. If we're doing vocals as a band thing, I'm the leader in the session, because I'm kind of arranging, chasing the cats. And when I'm in there by myself, putting on guitar overdubs, I don't care if I'm in there all day with Rick, and holding hands, when the red light comes on and my guitar part comes one, whether it's an hour or it's four hours, I'm getting paid double scale for that. Okay?" "Okay." The album's out. About a month later, I call the union and say, "I haven't gotten my checks yet." So they called Epic and kicked up a fuss. There was no paperwork. The album was released and nobody turned in any paperwork for the musicians. And the union was pissed off at Epic and was going to fine them. And then Epic was pissed off at Rick and blah-blah-blah-blah. And I get a phone call from Rick -- "Denny, what's the deal, man? You're calling up the union and you're making a lot of trouble and problems for everybody? The record company's pissed off at me, man. What do I need this shit for? What are you doing?" And I said, "I wasn't doing anything. I did my job. And I just called up, 'Where's the check?' I signed the union paperwork. He didn't turn the things in." This stuff kept happening, "You see, Denny's making trouble. Denny in the Winnebago, we were all happy that we broke the record in the mall. And Denny was complaining all the time. Denny's always bugging about everything. Denny's always grumpy," Yeah, it's called "our career's going down the tubes." We're playing these bullshit clubs, nowhere, in the middle of a record promotion. And I'm sure it got to the point where I was grumpy. Everybody was grumpy. So I just got a call one day, "Hi Denny, I've got to let the band go. It's a matter of not having enough money. I've got to let the horses go. I had to sell the horses." "Oh, you had to sell the horses, wow, man, I didn't know. Wow, man, I'm sorry. I didn't know it was that bad. How much money have the horses been making you?" And that was it. We just parted. And then the manager and the agent started booking him on these rock 'n' roll revival tours. And the next time Rick popped up, he was on like "The Tonight Show." He also did a couple of singles and he did some Al Kooper. And he was doing a rockabilly album, bringing back rockabilly. If he'd said to me, "I really want to do a rockabilly album and bring it back," I'd have said, "Great. You write a couple of rockabilly songs, I will. But we're not doing 'Be Bop Baby.' We're doing like a contemporary version of that." But these people were just doing like these little clone versions of it. Those didn't sell. And he just wound up on these rock 'n' roll revival tours with Fats Domino and Jerry Lee Lewis and wearing like kind of the prom outfit with the black shirt and the skinny white tie and white bucks and just like of overdriving it a little bit more, trying to make it a little more Elvis-y than Rick. So he did those tours. So the manager was getting his commission; the agent was getting his commission. PCC: SAROKIN: And the guys in the band towards the end were like, "We don't see Rick. We just see him on the stage. He just comes in and walks out there." He had a girlfriend at the time. To me, even though the name dribbled on, we were the end of the Stone Canyon Band. We were the second version. You know, the drummers changed out, but basically, we were the core of it, me, Tom and Jay DeWitt White. That was the second generation and then it was no more Rick Nelson and the Stone Canyon Band, meaning there was no Rick Nelson writing songs, Rick Nelson being the front man of like a personal, contemporary unit sound. And with those big harmonies. It wasn't about any of that anymore. So that was the one sort of regret, that he didn't pursue more of the songwriting. I think he just scratched the surface. Again, he did some songs that were worthy of any songwriter. Like "Garden Party" was the epitome of taking a life experience, a bad experience and just whap! Success is the best revenge, getting a hit out of an unpleasant experience. And more importantly, the song says, "You can't please everyone, so you've got to please yourself." It was this Zen, gestalt overview... But that was then and this is now. With my new CD. PCC: SAROKIN: And back to your original question about the core, it's a lot of me. And it's me stepping away from me in terms of that highest power that happened to come through me. On something like, "Never Too Old" on the new album, you're never too old to rock 'n' roll. Yeah, it's a literal story of every guitar player. But there's a higher message -- that you can do anything you want to do. And don't let age, don't let circumstances drive what you want to do. That song "Dream Big," when he was being interviewed about his Olympic success, Michael Phelps, said, "If you're going to dream, you've got to dream big." I heard that and pulled into a parking lot and took out the voice memo to get that down. And to me, the song has a metaphysical message. I have that song "I Built That." I think it's a song that America needs. That's another one of those songs like "Founding Fathers," that MAGA people and liberal people can all relate to. Hard hats can say, "Yeah, I built something." And teachers can say, "I build people's minds." All kinds of people can say, "I go to work and I make a difference. I make something bigger, better. I work to improve people's lives, to improve society." PCC: SAROKIN: PCC: SAROKIN: PCC: SAROKIN: My father was this card-carrying atheist. And I had to come up with something that I'd be singing for like a room full of leaning-towards-Orthodox Jews. And my mom was a super-Jewish mother, which is more a cultural thing than teaching you anything about the religion. So I took my mother's super-faith and my father's self-proclaimed no-faith and my own "I'm on this journey" and sort of came up with an agnostic anthem. Music is more powerful, if you can ask the right questions, rather than giving the answers. Same thing with "The Return." It's poetic, a kind of Jackson Browne-y type of thing. "From love we come and to love we shall return." But where? Where do we come from? Where are we going, returning to? I don't know the answers. I'm not a born again Christian, who says, "Okay, Jesus Christ and St. Peter are going to meet us at the gate and grandma will be there." On this spiritual anthem, I'm leaving it with an enormous question mark, because I can't honestly give you the answers. I'm just raising some questions. I don't know, but I hope there's "a place of peace, a place of light, a place where lonely hearts and loved ones reunite." I like to have a message underneath, a sort of spiritual underbelly of the song. To listen to Denny's music, purchase "Founding Fathers'" or to check out some of his performance and instructional videos, visit www.dennysarokin.com. Thanks to friend and fellow Rick Nelson aficionado Ian Cooke for his help in setting up this interview. |