DON MURRAY: A MEMORABLE, MEANINGFUL LIFE IN FILM

"Bus Stop" Was Only The First Stop on a Remarkable Creative Journey

By Paul Freeman [July 2018 Interview]

Authenticity.

Whether he's playing a rowdy, ingenuous cowboy, a desperate drug addict, a crusading priest, a medical student drawn into the IRA, an accountant tempted to cheat on his wife, a closeted gay senator, a rogue cop, an alcoholic jazz buff, the governor of a police state that oppresses apes or that eternal optimist, Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, we believe Don Murray. He never settles for a false moment. Every word, every gesture has the ring of reality. In Murray's eyes, there is truth.

That's partly due to Murray's mastery of the acting craft. And it's also a reflection of his integrity, both as an artist and as a man.

He was born on July 31, 1929, in Hollywood, but grew up in New York. An exceptional athlete, Murray turned down college scholarships to study at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts.

Murray made his Broadway debut in 1951, in the Tennessee Williams drama, "The Rose Tattoo." Then his career rise was temporarily halted by the call to service. He filed as a conscientious objector, which was a courageous stance in the Korean War era.

Murray had no intention of evading his responsibilities, however. So he volunteered to go overseas with Brethren Service, helping orphans and war casualties. From 1953 to 1956, he worked devotedly in Germany and Naples, Italy, which had been heavily bombed during WWII. In Sardinia, he organized the Homeless European Land Program (HELP) which, on 135 acres, built homes and established businesses providing both a community and employment for refugee families.

Upon his return, Murray was cast opposite Marilyn Monroe in 1956's "Bus Stop." Murray's immensely appealing performance as a rambunctious, but innocent modern cowboy earned him a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award nomination and helped Monroe deliver one of her most cherished portrayals.

At that point, with his leading man looks, natural charm and infectious grin, he could have starred in a string of romantic comedies. Or, given his ability to inject a steely grit into a character, he could have been a hit in westerns and action films. But Murray wasn't willing to fit any studio mold. He eschewed fluff and chose diverse roles in films of substance. And his presence gave many outstanding films an even greater weight. He found the complexities in his characters, often bringing more to a role than was on the page.

Murray's movies tend to be powerful and exciting, but rarely purely escapist fare. Yes, he could generate electricity in love scenes with such leading ladies as Lee Remick, Eva Marie Saint, Diane Varsi, Dana Wynter, Anne Francis and Inger Stevens. But in each case, romance merely served the larger story, adding spice to his multidimensional characters.

Too often, the dramatic arts have less to do with art and more with commerce. Murray is a true artist, one who has, not only as an actor, but as a screenwriter, director and producer, brought to light many important themes over the years, including peace, non-violence, equality, faith and redemption.

He followed "Bus Stop" with a stunning performance as a vaunted veteran who returned from the Korean War with a morphine addiction. Then he led a superb ensemble cast in Paddy Chayefsky's comedy-drama "The Bachelor Party." 1959's "One Foot in Hell" was one of Murray's top-notch westerns, which avoided the typical superficial hero. "Shake Hands with the Devil" teamed Murray with James Cagney in a tense film about the conflict between Ireland and oppressive English forces. In 1962, Murray starred in the timely "Escape from Berlin" The Cold War suspense film was based on a daring, actual event.

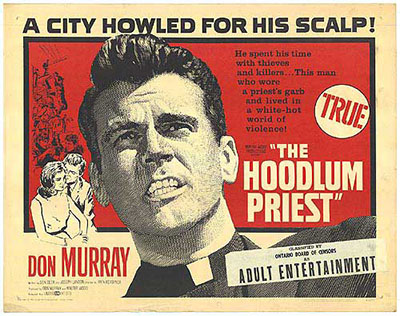

Murray turned to religious figures for three true-life stories. For "The Hoodlum Priest," Murray served as a screenwriter and co-producer, as well as star. He gives one of his finest performances in the role of Fr. Charles Dismas Clark, who ministered to St. Louis street gangs. The film presented an unflinching depiction of capital punishment that's still jarring today.

In another of his 1960s films, "One Man's Way," Murray memorably plays Norman Vincent Peale, who began as a crime reporter and wound up a minister, penning the best-selling, "The Power of Positive Thinking." In 1970, Murray wrote and directed "The Cross and the Switchblade," the story of a crusading minister, David Wilkerson, who changed the lives of New York City youths, whose lives were being destroyed by drugs and violence. Pat Boone starred. Erik Estrada made his screen debut, and, guided by Murray, delivered a striking portrait of one of the main gang members.

In 1967's impressive independent film "Sweet Love, Bitter," Murray played a former professor, drowning his guilt in booze, who is befriended by a tragic, Charlie Parker-like saxophonist.

In the 70s, other notable Murray movie appearances came in the Kurt Vonnegut adaptation "Happy Birthday, Wanda June," as a dangerous New York cop in "Deadly Hero" and as the villainous Governor Breck, who torments the simian slave population in "Conquest of the Planet of the Apes."

In the 80s, Murray highlights included playing Kathleen Turner's dad in "Peggy Sue Got Married" and Brooke Shields' father in "Endless Love."

But the big screen wasn't Murray's only avenue. He also made his mark on TV. He starred in the first movie ever made for television, the highly effective "The Borgia Stick." Another 60s thriller also garnered high ratings -- "Daughter of the Mind." Tons of additional made-for-TV movies followed, many dealing with topical issues, including "Thursday's Child" (heart transplant), "The Boy Who Drank Too Much" and "The Quarterback Princess" (equal rights for girl athletes). "A Girl Named Sooner," about a rural foster child, earned much acclaim.

Murray has made guest shots on many popular series, including "How The West Was Won," "Police Story," "Matlock," "Wings" and "Murder, She Wrote."

His 1968 series "The Outcasts," co-starring Otis Young, was a riveting, ahead-of-its-time drama revolving around two bounty hunters, one black, one white, in the post Civil War West. Murray was also a regular in 1989's "A Brand New Life" and 1991's "Sons and Daughters." TV fans fondly remember Murray as Sid Fairgate, Michele Lee's husband, on "Knot's Landing."

David Lynch brought Murray back to the screen for 2017's return of "Twin Peaks." Murray engagingly played Bushnell Mullins.

About to turn 89 at the time of this interview, Murray remains vibrant, active and creative. He has just completed a book relating to his time with Marilyn Monroe.

Family remains at the heart of Murray's very full life. He was married to actress Hope Lange for five years and they had two children, Christopher and Patricia. Since 1962, he has been happily wed to former model Bettie Johnson (who made several brief screen appearances, under that name and Betty Murray). They have three children -- Sean, Michael and Colleen (married to artist/musician Christopher Otcasek of the band Glamour Camp and son of The Cars' Ric Ocasek),

We hope there will be more Don Murray films in the future. In the meantime, his remarkable body of work continues to enlighten, inspire and entertain. The truth is timeless.

Mr. Murray generously took time to talk with Pop Culture Classics.

POP CULTURE CLASSICS:

Your parents were both in show business at one point?

DON MURRAY:

Yeah, that's right. My mom was a Ziegfeld girl. And also in Vaudeville. And then later, on the Broadway stage, as an actress. And my dad was a singer first and he taught himself to dance and became a dance director on Broadway. And then when the talkies came, he was hired by Twentieth Century Fox to be a dance director in movies.

PCC:

So did they have lot of great stories and interesting people around that made you think this was the life you wanted to follow?

MURRAY:

Oh, yeah. This is what I always wanted to do, since I was four years old. I always wanted to be on the stage.

PCC:

So was it mostly just observing what was going on with your parents? Or did they actively encourage you to get involved in the arts?

MURRAY:

Well, they encouraged all their three children to just do what they wanted to do. And I chose to follow in show business. My brother was an engineer and my sister was a teacher, so they didn't follow it. But I did.

PCC:

Did your parents also give you the foundation of your social conscience or where did that spring from?

MURRAY:

Yeah, it definitely sprang from that. They were, particularly my mother was very, very active. She had a newspaper column. And she was very active in social services. So that spurred my interest, as well.

PCC:

And so, even though your dad was working for Fox, you were based in New York as you were growing up?

MURRAY:

Actually, we lived in Hollywood for the year he was with Fox. What happened was that he was just with Fox for a year, when the Depression hit in 1929, when I was born. And the studios thought that the Depression was going to be a bad time for them, so they closed temporarily. And so Dad went back to New York, went back to being a stage manager on Broadway. And what they found was that the Depression was the greatest thing that ever happened to movies, because it was cheap entertainment for 10 cents, and a double-feature. And it was a way for people to forget their troubles of the Depression. So it was big for movies, but Dad had already gone back to Broadway.

PCC:

Were you more often hanging out at the movies or going to Broadway and off-Broadway plays and getting into that scene?

MURRAY:

Well, I never saw a what we called a straight play -- not a musical Broadway play -- till I was 16 years old. Until then, I had only seen musicals. And that's what I wanted to do. My idol was Danny Kaye. And I wanted to be a comedian and be in musicals.

But then I went to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. And when I was cast as a dying Scot soldier in a play called "The Hasty Heart," I really saw the power that dramatic plays have on people, have on people's emotions. So I turned into what we'd call a "straight actor," non-musicals. I never ended my love for musicals. I went back to New York and did an off-Broadway musical back in 1973. So I've always kept my love for musicals, but my career has been really mostly in drama.

PCC:

So your time at American Academy of Dramatic Arts -- surrounded by other gifted artists starting out -- how important was that to your development?

MURRAY:

Oh, it was very important. The important thing, for me, was the Academy. The teaching I had there just lasted me for all my life. My approach to playing a part, that was developed at the Academy. And they followed the Stanislavski method, which is, just very simply, that you don't represent emotions -- you actually feel the emotions of the character and express what comes out of your feelings, rather than sort of making faces [laughs].

PCC:

And being able to get into the "Method," was that something you really had to toil at developing? Or did it come naturally to you?

MURRAY:

It came very naturally, because it was the most natural way of acting. One of my great teachers there, a man named Paton Price, who later became my personal coach, when I got into movies, he used to say, "Talking and listening is the essence of art." You listen to what people say and the way someone says something to you and it stirs an emotion within. You don't have to force anything. Everything comes from the reality of the situation that you're dealing with. I guess they would call that "Method," Stanislavski's method, because that's what he taught.

PCC:

Then there was the interruption in your trajectory, with the service. You applied for conscientious objector status. That was a brave stand at that point. It wasn't as common as it became in the 60s.

MURRAY:

Well, there was no one else that I knew that was going through that at the time. I was not granted that status at first. I was drafted into the Marine Corps. And when I went to be inducted, I refused to be inducted and so I was actually in jail. I was under arrest for a month, but I was only in jail for less than one day. I was out on bail. And the District Attorney ended up refusing to prosecute, because he realized that I was serious and that I was not trying to avoid the draft.

As a matter of fact, I volunteered for service in Korea as a civilian, in a healing capacity, as a medic. But I was not accepted for that. And I finally joined a group called Brethren Service, which was the forerunner of the Peace Corps. And I served for two-and-a-half years for them. I had signed up for two years, but then I stayed for an extra six months, because I was working with refugees and I wanted to finish the work I was doing with them, and later on, with a social visionary named Belden Paulson. We bought some land on the island of Sardinia and we started a refugee free community, took them out of their barbed wire camps, where they were living almost like prisoners and gave them a free life in this community, which is still surviving today. It's a very flourishing community.

PCC:

With your experience with refugees, how do you react to the issues of immigrants and refugees that's still a timely topic?

MURRAY:

Well, today the refugee problem is so enormous. We're talking about millions of refugees. At that time, the refugees in Europe, they numbered about 50,000. And now we're talking about millions of refugees. It's a tremendously different situation today. I'm not sure my concept of building a free community would work today, because there's too much political turmoil, too many nations that don't want the refugee situation solved, because they want that ferment to continue for their own political goals. So it's a very different situation today.

PCC:

But working with the refugees back then, did that have any influence on you later, in terms of your acting career, in terms of wanting to accomplish something through the arts that would reflect your humanity?

MURRAY:

Yes. And as a matter of fact, after I did "Bus Stop," at the end of the year, 1956, I had written a screenplay about the refugees in those barbed wire camps. And it was bought by CBS and it was performed on "Playhouse 90" [the episode titled "For I Have Loved Strangers"]. And Hope Lange, then my wife, and I starred in it. And it was one of the more successful shows. And that showed the refugee problem.

PCC:

Yes, you were able to do some important work in live television -- "Billy Budd," another "Playhouse 90" about the aftermath of a nuclear holocaust...

MURRAY:

Oh, yeah, "Alas, Babylon."

PCC:

Right. Was that an exciting time with all that was happening in television drama?

MURRAY:

It was a very exciting time. As a matter of fact, "Alas, Babylon," critics were writing about it, saying that this was going to cause people to write their Congressmen and do something about nuclear weapons, because that was about nuclear conflagration.

PCC:

And then you did "A Man Is Ten Foot Tall" with Sidney Poitier.

MURRAY:

Yeah, that was a racial theme. And as a matter of fact, ABC came to me back in 1968 and they offered three scripts and said, "Whichever you pick, we'll put on the air without a pilot and you'll be guaranteed at least a year." And what I picked was one called "The Outcasts," which was a racial theme about two bounty hunters. One was a former slave and one was former slave owner. And I did that with a wonderful black actor called Otis Young. And that was part of the racial theme.

And also I did a movie later called "Call Me By My Rightful Name," which was taken from a Broadway play of the same name, starring Robert Duvall. When I did it for the movies, I produced it. And I hired Otis Young as the black actor in it. And he had understudied the part on Broadway, but didn't play it. So the film gave him a chance to play the role and he was wonderful in the role. It's a shame that it hasn't been more widely seen, because I think it was a very meaningful film, one of my favorites. And that also had a racial theme to it. So that's been an important part of my career.

PCC:

Yes, "The Outcasts" was a great series. There was such an intensity that came across in the relationship between you and Otis Young on the screen.

MURRAY:

Oh, good. Yeah, I was very pleased with the results of that.

PCC:

From that series, did you get much response in terms of presenting a positive role model for African-American kids? Now they had a cowboy hero.

MURRAY:

Oh, very much so. As a matter of fact, even today, especially when I go back to the New York over the years, I'm constantly having black people stop me in the street and saying how much they got from the show and how much it meant to their lives. So that was a wonderful outcome for me.

PCC:

And another of your films that dealt with racial themes -- I only discovered it recently -- the jazz-oriented "Sweet Love, Bitter." Very cool, moving, thought-provoking film.

MURRAY:

Oh, yes, with Dick Gregory. I'm glad you saw that. I like that. I thought that was very well written by a director called Herb Danska, who was a wonderful director. And I was very pleased by how that came out.

PCC:

Going back to your early stage work, in "Skin of Our Teeth," you had the opportunity to work with two of the great ladies of American theatre -- Mary Martin and Helen Hayes.

MURRAY:

Yeah, that was marvelous. I had just gotten back from my two-and-a-half years working overseas and I wasn't back for more than a week before I was headed right back to Europe again to play "Skin of Our Teeth" at an international film festival at the Theatre Sarah Bernhardt in Paris [The company was sent by the State Department in 1955 to represent the best of American theatre. Legendary playwright/director George Abbott also starred in this production of the Thornton Wilder absurdist comedy.] After we played Paris for four weeks, we came back and played Chicago and Washington and New York. And then they made a TV show out of that. So that was a wonderful experience.

PCC:

And for you, as a young actor, was that a growing experience, being able to work with actresses on the level of Mary Martin and Helen Hayes?

MURRAY:

Yeah, it was. And I was fascinated particularly by Helen Hayes, because I would always have to do preparation to get into the part before I stepped up on stage. And she'd be talking to a stagehand and say, "How is your son, James? He was going to college. Which college was he going to?... Hello, Henry!" [Laughs] And she'd be stepping right from talking to the stagehand to talking to the actor on the stage. She would immediately just fall right into the character. I was amazed by that. I could never do that.

PCC:

Acting in "The Rose Tattoo," did you have an opportunity to get to know Tennessee Williams? Did he spend much time at rehearsals?

MURRAY:

Yes, he was at all the rehearsals. And when we opened on Broadway, he was there and we rehearsed there, too. Even after it opened, we would have more rehearsals. And that was quite a big hit. It won the Tony Award as Best Play. And then we went on tour with it. So all in all, I played that role for a year-and-a-half.

PCC:

And what were your impressions of Tennessee Williams?

MURRAY:

Well, he was marvelous, in the sense that he was very appreciative of the actors and very complimentary to the actors. The first time we did a complete run-through of the play, without an audience, he came running down the aisle. He grabbed a hold of Phyllis Love, who played my lover in it, and myself, and he hugged us. And he was crying and just expressing his appreciation. He was wonderful to work with.

PCC:

And so, had Josh Logan seen you in "Rose Tattoo"? Is that what led him to cast you in the film "Bus Stop"? [Joshua Logan directed the film]

MURRAY:

Yeah, actually he had seen me in "Skin of Our Teeth." That was the main thing. And also he had auditioned me for a comedy that I was just too young for. And his wife [actress Nedda Harrigan], she reminded him of how much he liked me in my reading of the comedy that I was too young for. And so that give him the idea of screen-testing me for "Bus Stop." So I got into "Bus Stop."

PCC:

And had you seen the Broadway production with Kim Stanley?

MURRAY:

No, I hadn't seen it before I auditioned for the part. I saw it after I'd found out I'd be doing a screen test for it. Then I went and saw the play. And Albert Salmi played the part of the cowboy in the play. And he was wonderful.

PCC:

So that being your first film role, did Josh Logan help you to acclimate yourself?

MURRAY:

He did more than that. You know, I was nominated for an Oscar for that. And I said, if I won the Oscar, I'd have to cut off the head and give it to Logan, because he taught me how to play that part. That was Logan's performance more than my own. I've never received so much direction as I did from Logan in that. So I give him the credit for the success on that, with "Bus Stop."

PCC:

What was the biggest challenge for you, in playing Bo?

MURRAY:

Well, the major thing was to play the cowboy, because we didn't have much preparation time. We had only three days of rehearsal. I did the screen test and within a week, I was out to Hollywood, doing the three days of rehearsal and then going right in and playing this wild cowboy. And I'd never played a part like that before. The parts I played before were sort of more sensitive parts, not extroverts, but more introverts. So this was something I really depended on his direction for. And I appreciated it. I just followed his direction.

PCC:

Did you actually learn to ride for the role?

MURRAY:

I couldn't. I didn't have time to learn to ride, as a matter of fact. What I did [chuckles], they'd have me on the chute, like when I'd do a steer wrestling thing, they'd have me ride out of the chute and then when I found myself being jiggled off the horse, I'd grab the saddle horn to hold on. And they'd cut before I grabbed the saddle horn. So that's how I was able to ride the horses. I didn't really know how to ride. I just tried to get out of the chute alive. The worst thing was sitting on the Brahma bull [laughs]. The Brahma bull trembled like a vibrator. It was such a nervous animal.

PCC:

In your subsequent westerns, you always seemed so comfortable in those cowboy roles.

MURRAY:

I got to be comfortable, because there was a wonderful cowboy and he taught me to ride. And he taught me everything about riding. And he started me on bareback. He said, "You've got to learn to ride a horse, not a saddle." And he did everything with me. He showed me how to take care of the horse. And he turned me into a cowboy. And I got to be very comfortable riding, in all the shows I rode in after that. I didn't have to have people riding for me unless there was a fall from the horse or something like that. Then a stuntman would do it. Otherwise I could do all my riding, because he had taught me so well.

PCC:

Going into "Bus Stop," was there extra pressure, knowing that you'd be playing opposite the biggest screen sensation of the day, in Marilyn?

MURRAY:

Well, you know, I wasn't really very conscious of that, when I walked into the situation, because I had been in Europe all this time. And I had seen her in "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes" over there, but the big stars, to me, were Gina Lollobrigida and Sophia Loren, the Italian stars, because I was watching Italian movies. I spoke fluent Italian. So those two were more impressive to me than Marilyn. I didn't know that much about Marilyn. I had only seen her in that one movie.

So it was a surprise to me to see that there was such a fuss about Marilyn. It was her comeback movie after leaving movies for a year to study acting at Actors Studio. And the press was constantly around her, whenever they were allowed on the set. They were usually kept off the set while we were filming. But they were always waiting outside and it was like acting in a fishbowl.

PCC:

Wasn't that a major distraction for a newcomer to film, when so much production energy had to be geared to accommodating the star?

MURRAY:

Well, yeah, the big problem -- and fortunately I realized that this was a problem just after the first day of shooting -- is I realized that I had to try my best to be at my best on every take, because whatever take Marilyn would be at her best in, that's the one they'd use. [Laughs] As long I didn't forget my lines, whatever was the best scene for her would go in the film. So I had to be on my toes and try to be at my best on every take.

PCC:

The magic that came across when she was on screen, was that evident as you shared the scenes with her?

MURRAY:

You know, not really, because she did her scenes in small bits, because she would lose her concentration. She wasn't able to get through a long speech without stopping. So it was constantly stop-and-go, stop-and-go, all through. So I didn't realize how good she was until I saw the movie. And then I was absolutely floored by her.

I thought she was magnificent. I thought she deserved to win the Academy Award that year, because I thought she gave the best performance of the year. I mean, Ingrid Bergman was very good in "Anastasia," but she was doing something that she'd always done. And Marilyn was doing a character that was completely outside of her. Even though she used her own emotions, the character that she played was something that she'd really have to work on. And she did. And she was wonderful. I just thought she deserved an Oscar. As a matter of fact, she was never recognized by the Academy. Not only did she never receive a nomination, she never received any Lifetime Achievement Award or anything from the Academy, which really startles me.

PCC:

During that shoot, how did her insecurities manifest themselves? Did you see much of that side of her?

MURRAY:

Yeah, as a matter of fact, she broke into a rash, when she was acting. She broke into a rash all over her body, a big rash. And they'd have to dab it white makeup. And she would stop-and-go a lot during the filming. It was hard for her to have the continuity of a scene. They'd have to put the scene together in pieces. And the editor, whose name was Reynolds [William H. Reynolds], he did a fabulous job in cutting her together. And of course, it was Logan's direction of her -- he was very, very patient with her. And as a matter of fact, they said that was her best behaved film -- working with Josh Logan.

PCC:

Was she also relying on Paula Strasberg [Marilyn's ever present acting coach/confidante, wife of Lee Strasberg] at that point?

MURRAY:

Yes. And as a matter of fact, Logan didn't resent Paula. He just said, "You can do any work you want with Marilyn. You just have to do it off the set. You can't direct her on the set. But you can work with her off the set." And he used her as an aid, rather than an obstruction. And I know that when she did "The Prince and the Showgirl" with Laurence Olivier [who produced and directed, as well as co-starred], he felt that Paula was a terrible distraction. But Logan didn't. Logan used her to his advantage.

PCC:

Did you have any sense that Marilyn was a tragic figure in the making?

MURRAY:

No, not at all. Not one bit. I was amazed. I don't really believe she committed suicide. She took a lot of pills. She took pills to go to sleep, pills to wake up, pills to calm down, pills to get energy. And I think she just lost track of the number of pills she took and she took an accidental overdose. I think that's what happened, the most likely explanation for her death.

PCC:

You're working on a book detailing how your lives intersected? Or is it completed?

MURRAY:

Yes, I already finished the book. It's called "Marilyn Monroe and her Bo." I was asked to write a book by Random House, way, way back, when I first came out in movies. And so it just took me 50 years to write it [laughs].

PCC:

Do you know when that will be published?

MURRAY:

I don't know, because I haven't sent it to Random House yet. I intend to do that soon.

PCC:

Hope Lange had a memorable part in "Bus Stop," as well.

MURRAY:

Yeah, she did. And she had quite a career afterward. Won two Emmy Awards in a row. Also she was nominated for an Academy Award for "Peyton Place." She had a quite a distinguished career.

PCC:

And so you knew each other, had worked together before, but weren't married at that point?

MURRAY:

No, as a matter of fact, we had known each other for four years before. And we were engaged at the time that we did the movie. And they put out the publicity that we met on the set [laughs], but that wasn't true. We were engaged. They hired each of us without knowing that we knew each other.

PCC:

Receiving your Oscar nomination -- that must have been so validating.

MURRAY:

Well, it was a complete surprise -- to everybody, because nobody took out any ads. I didn't take out any ads to get the nomination. I didn't take out any ads to get the award. So it came as a surprise to everybody, including myself and including the studio, because they were amazed that it happened spontaneously.

PCC:

What do you remember about that Oscar night?

MURRAY:

Oh, I just remember, I was there like a member of the audience. It actually was a disturbing appearance for me, because somebody had written seriously in the Long Beach paper, and then it was picked up by the Hollywood papers, that I had tried to influence the Academy to try to put me in the Supporting Actor category, because I knew I didn't have a chance as the leading actor. Well, this was so ridiculous, because I came from the Broadway theatre and I didn't know what the Academy or where the Academy was, much less trying to influence it [laughs].

The nomination had happened completely spontaneously. So that really bothered me, because it was something that I would never do. And so that nomination wasn't my happiest in Hollywood. That was more of a bother than it was something that I really appreciated at the time. I appreciate it now, because lots of people have shown interest in my other work, because of that nomination. So I appreciate it -- now I'm glad it happened. But at the time, it was not a happy experience.

PCC:

Your performance was such a success, as was the film -- was there any thought of, "How do I live up to this success?"

MURRAY:

I never really thought about that. My next one, I was offered all these extroverted, adventure kind of parts and I turned them all down, because I wanted to do something just the opposite. I didn't want to be typecast. So the second film, what I selected, was "Bachelor Party," from a Paddy Chayefsky play, which was a drama and a very introverted kind of character. And that film was a successful film and I got a lot of good reviews. So that turned out to be a happy choice for myself.

And then I did a dope addict in "Hatful of Rain." And when Buddy Adler, the head of the Twentieth Century Fox studio told me he bought the film for me, he bought it for me to play the brother, who Anthony Franciosa ended up playing. He expected me to play the brother, because that had a lot of comedy to it. And I said, I didn't want to play the brother, I wanted to play the dope addict.

So the director, Fred Zinneman and Buddy Adler, the studio head, agreed that, if I wanted to play the dope addict, I could. So I ended up playing the dope addict. And, of course, Tony Franciosa played in the movie what he played in the Broadway play. And he received an Academy Award nomination. And also he won Best Actor at the Venice Film Festival. So it was a good thing for both of us.

PCC:

Such an unforgettable performance you gave -- there is not one inauthentic moment. How did you find the truth of that character. Did you study people who were struggling with addiction?

MURRAY:

Yes, I did. With Fred Zinneman, I spent a month in New York City, studying about that, not only in jails and doctors' offices, but actually went to some of the places that were their hangouts at night, these abandoned buildings in Manhattan, and we watched them shoot up and so on. So I really saw firsthand what they're like. And I saw them in withdrawal symptoms. I saw all phases -- the lack of drugs and then what happened when they had the drugs and so on. So I just learned from that, from reality.

PCC:

It's a great cast -- Eva Marie Saint, Tony Franciosa, Lloyd Nolan -- you had compelling scenes with each of them.

MURRAY:

Yeah,they were wonderful actors.

PCC:

You mentioned "Bachelor Party." Paddy Chayefsky adapted his play for the screen. Was he on set much?

MURRAY:

Yes, he produced it, as well as wrote it, so he was on the set the entire time.

PCC:

He must have been quite a presence.

MURRAY:

Oh, he was. He was amazing. And [chuckles] he had us do some improvisations. In the scene, we're supposed to be watching a porno film, so he had us just improvise our reactions. And Jack Warden gave the best reaction of all. He says, "Ah, you seen one, you seen 'em all... You wanna run it backwards?" [Laughs]

PCC:

They had you actually watching a stag film?

MURRAY:

Yeah, they filmed us while we were watching one. And that's when he made that remark.

PCC:

So were you under contract to Fox at this point?

MURRAY:

I was not under exclusive contract. I had been offered movie contracts throughout my Broadway career, but I always turned them down, because they were what I call "slave contracts," where they could put you in whatever films they wanted. And I turned down

"Bus Stop" at first, when they insisted that I sign what I call a "slave contract." And I turned it down and then they came back and they agreed to a non-exclusive contract.

So my contract was two pictures a year for six years. And then I was free to do work wherever I wanted, when I wasn't doing those two pictures for them. That's how I finally got into movies, after years of turning down films.

PCC:

So that's how you were able to achieve such diversity in the roles.

MURRAY:

Yeah, exactly.

PCC:

So were you turning down roles that might have been more obviously commercial to pursue material that would be artistically satisfying?

MURRAY:

Oh, yeah. One I turned down was "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof." I turned it down, because I had just done the dope addict and I didn't want to do another introverted, disturbed character. I wanted to do something the opposite. So what I did instead was "Shake Hands with the Devil," about the Irish rebellion against the English. And that starred Cagney and myself, with Richard Harris.

PCC:

Was that a controversial subject at the time, dealing with the IRA?

MURRAY:

Oh, yes, very much so. As a matter of fact, they were very careful to collect all the guns from everybody and also to make sure that no real ammunition got into the guns. They were very careful about that.

PCC:

And James Cagney -- had he been one of your screen idols?

MURRAY:

Oh, yeah. He was my hero from "The Fighting 69th" and also the fabulous "Yankee Doodle Dandy." He won the Academy Award for that one. He was such a great musical comedy performer, the best.

PCC:

And what was it like, working with him?

MURRAY:

Well, he was like old-school kind of acting. Like he would very often try to break you up in the middle of a serious scene. He would fool and do things like that. He was kind of playful, which was kind of surprising to me.

And I would always lift weights on the set for exercise. And he would just tap dance for exercise. And he'd do it constantly. It was quite marvelous to watch. I just loved doing the film, because of that. And also because of the subject matter and the screenplay and the direction. It was really a great experience.

And shooting in Ireland, just being in Ireland -- what a wonderful experience. The Irish people are so marvelous. I remember the first taxi cab I got into in Ireland. And after we arrived at the studio, I said, "How much do I owe you?" And he said [in an Irish accent], "Well, the meter says three shillings, but just give me two, because I gave you a hell of a runaround." [Laughs] They wouldn't say that in New York.

PCC:

And that was the first feature for Richard Harris.

MURRAY:

Yes, it was. As a matter of fact, I brought Richard Harris to the States, right after that, I did a live television show called "The Hasty Heart" and there's a part of an Australian soldier in it. And I brought a picture of Harris and I said, "Hire this guy for the part." They said, "Well, great, let's read him." I said, "You can't read him. He's in Ireland." And they said, "Well, we can't being him all the way over from Ireland. We have to go through our casting department. The advertising agency has to have approval."

I said, "I've never done this before and I'll probably never do it again -- just hire the guy sight unseen. You pay for his fare, bring him over here. And if you don't use him, I'll reimburse you for his airfare." They said, "How can we lose? Okay." [Laughs] So they did it. They brought him over. And I sure didn't have to reimburse them, because they thanked me profusely for bringing him.

PCC:

So you had recognized instantly, from "Shake Hands with the Devil," what Harris had.

MURRAY:

Yeah, even with his small part, I knew that he was something really special.

PCC:

And then "From Hell to Texas," this was not really a typical western hero. He was more afraid of killing than being killed. Was that an enjoyable project for you?

MURRAY:

Yeah and I chose the project particularly because of its theme, its non-violent theme. And I had a wonderful teacher called Rodd Redwing, who was an American Indian. And he was a rifle and a pistol expert. And he taught me to use that rifle as if it were a pistol, to load it with one hand. All the tricks I had with it, I learned from Rodd Redwing.

PCC:

And Diane Varsi, the female lead in that film, the two of you had great interplay. I had read that she was very uncomfortable with stardom. Did you get any glimpse of that?

MURRAY:

Well, she, of course, was nominated for "Peyton Place," along with Hope Lange. And she was very, very good to work with, just very real. I really enjoyed working with her. I think, later on, she got more complicated. But she wasn't complicated in that. She was very cooperative and very easy to work with.

PCC:

And that was an early Dennis Hopper film, as well.

MURRAY:

Yeah. Well, Dennis Hopper was another thing [laughs]. He was a real problem.

PCC:

How so?

MURRAY:

Oh, my God, he was fighting with the director all through the show.

PCC:

And yet, he worked with that director, Henry Hathaway several times, didn't he?

MURRAY:

He worked with him at least two times after that, maybe three.

PCC:

And another of your westerns, "One Foot in Hell" -- what were your impressions of Alan Ladd at that stage of his career?

MURRAY:

Well, unfortunately, Alan Ladd had a tremendous drinking problem. And that affected his performance. Ironically [chuckles], I was playing an alcoholic. I was playing the drunk. And it felt pretty ridiculous, because I couldn't compete. But that was really difficult, because that was a time when he was having real personal struggles with his demons. So that was sad to watch, because I remembered him in those marvelous film noir movies like "This Gun for Hire." And that was a difficult time.

PCC:

With "The Hoodlum Priest," I guess that was a very personal project.

MURRAY:

Yeah, that was my most critically acclaimed film and I had written the screenplay under the name Don Deer...

PCC:

Why Don Deer? And why use a pseudonym at all?

MURRAY:

That was a nickname I had in high school, from running. And I just thought it would be romantic to have a nom de plume. Great mistake, because a lot of people didn't believe I wrote the movie.

PCC:

That movie must have had a lasting impact.

MURRAY:

It did. It won five international awards, but what was really nice about it is that I get letters from people saying how it had changed their lives. Several became priests because of it and other people became social workers. It had a great effect on the public. That really pleased me.

PCC:

And certainly one of the most dramatic depictions of capital punishment.

MURRAY:

Yeah, that's true.

PCC:

Did that spark a lot of controversy at the time, because the film might sway people to take a stance against capital punishment?

MURRAY:

There was not a big controversy about that. Except, the only place was right there in St. Louis itself, where we shot the film. The real priest, Father Charles Dismas Clark was from St. Louis. And some of the newspapers there panned it, that part of it, not artistically, but sociologically. They panned it for its anti-capital punishment position.

PCC:

And a great performance by Keir Dullea in the film.

MURRAY:

Yeah, it was. He was just wonderful in it

PCC:

And then "One Man's Way," Norman Vincent Peale -- playing an inspirational role like that, does that stick with you? What did you take away from that experience?

MURRAY:

Yeah, well, what I took away was just getting to know Dr. Norman Vincent Peale. He was one of the nicest and one of the most humble people that I have ever met in making movies, just wonderful. He was very complimentary about my interpretation of his life and so on. He was great. He was on the set a lot. And I got to know him. And he ended up baptizing our baby. My wife, Bettie Johnson, whom I married during the making of "Escape From East Berlin," we got married in Germany, and our first baby was baptized by Norman Vincent Peale. So that was a great part of my life. That meant a lot to me.

PCC:

And then "Advise and Consent," which was ahead of its time, in that it had your storyline, a closeted gay politician, facing political blackmail. Did you consider it a risk, to take on a role like that, in terms of your image? Or was that irrelevant?

MURRAY:

No, it was irrelevant to me. I didn't care about that at all. As a matter of fact, Otto Preminger [the film's director] brought it up to me, when he told me he wanted me to play the part. He says, "Are you bothered by this?" And I said, "No, not a bit. It's an acting role."

PCC:

He could certainly be tyrannical. How was he with you?

MURRAY:

He only picked on people when he thought he could get away with it [laughs]. But like most bullies, when you stand up to bullies, they back down. So I didn't have any problem with him. As a matter of fact, it was funny, my wife, Bettie Johnson, who was a top New York model, she was visiting me on the set. And he saw her and asked her to play a walk-on role in it, a non-speaking role, but one that stood out, in the sense that it was this beautiful, high-class call girl leaving the apartment of one of the senators. [Chuckles] And he asked her to play it. And she said, "No, I'm not going to do a movie with you, Otto." He said, "Why not?" She said, "Because you yell at the actors and I don't like that." He said, "I don't yell at the actors, I only yell at the crew." I said, "Yeah, like Henry Fonda, the makeup man and Charles Laughton, the chief grip" [laughs]. But anyway, she did play the part.

PCC:

[Laughs] He certainly wouldn't yell at Fonda, the actor or Laughton, the actor.

MURRAY:

He did not. He did yell, mostly at the cinematographer, in fact.

PCC:

Shooting in Washington, D.C., was there much interaction with the real politicians?

MURRAY:

Absolutely. We had lunch with the President (JFK), with just six of us from the show... and Jackie. And afterwards, Jackie gave me a private tour of the White House. And then we were also on the Presidential lot, where they hosted a party for us. So we had a lot of time with the President and Jackie... and Bobby, too.

PCC:

With your strong values, did you get much involved, in the 60s, with the peace movement?

MURRAY:

Yes, I did, very much -- the peace marches and so on, and letter-writing and talking with Congressmen and so on. And my book has a lot of that theme to it, as well.

PCC:

Now, "Baby The Rain Must Fall," was it mainly the opportunity to work with Robert Mulligan (the director) again, that drew you to it?

MURRAY:

Yes, it was, because I had done, of course, "Billy Budd" [1959 episode of "The DuPont Show of the Month"] with him. And also I had done a live television show, Sidney Poitier and I, called "A Man Is Ten Feet Tall" [1955 "Philco-Goodyear Television Playhouse], that was directed by Mulligan. So I'd worked with him very successfully before that.

Yeah, "Baby The Rain Must Fall" was on just a couple of nights ago [on TCM]. And I was disappointed in that picture. It just didn't work very well, for me. I thought it was kind of boring, as a matter of fact. It was not an unhappy experience, because I was working with people I liked. But it didn't come out in an interesting way to me.

PCC:

It was certainly a change of pace for Steve McQueen.

MURRAY:

Yeah, very much so.

PCC:

Was he an intense guy on the set?

MURRAY:

Yeah, he was. I think that, though, he behaved himself well most of the time. But he did strange things, like he took the car once, when he was driving us to the set. And he took off across a field and got it up to 100 miles an hour and the thing ended up catching fire and we all had to jump out. [Laughs] That was quite an experience.

PCC:

And Lee Remick, who starred in that film, you worked with her several times. What were your impressions of her?

MURRAY:

She was just one of the best leading ladies that I had, one of the really top ones, along with Eva Marie Saint and Marilyn, of course. She was marvelous to work with.

PCC:

And then you did "The Borgia Stick." That was the first made-for-TV movie. Did you see the potential for a whole new avenue for drama with made-for-tv movies?

MURRAY:

Yeah, I thought it was a natural for it to be something that should catch on and continue. And of course, it did. They wanted to make a series of that, but I wouldn't do the series. So they let me do the film without doing the series. But I had to write to them that I wouldn't do any series for two years, unless I did theirs. But I didn't want to do a series, so it didn't make any difference.

PCC:

Your co-star, Inger Stevens, she had such a radiant screen presence. She had that vulnerability that came across. What was your experience like with her?

MURRAY:

Oh, it was like working with Lee Remick. She was one of the most wonderful people that I've ever worked with. She's marvelous. And it was heartbreaking to me, when she died.

PCC:

There were many theories about her death. You don't believe she took her own life?

MURRAY:

No, I didn't buy that.

PCC:

Why? You hadn't seen any indications..,.?

MURRAY:

I didn't see anything like that in her at all, the way she talked. She was so involved with things like civil rights issues and so interested in everything that was happening outside herself. She was not self-absorbed at all. And I just didn't see her as being someone who would take her own life.

PCC:

Then "Daughter of the Mind," working with Ray Milland and Gene Tierney late in their careers, what was that like?

MURRAY:

Yeah, I thought that was just a fascinating story. I thought it was a marvelous story -- the poltergeist that they create on the highway, so he thinks it's his own daughter. That was a marvelously imaginative screenplay. And it was very well done I thought, by the producers. I was very proud of that.

PCC:

And your impressions of Milland and Tierney?

MURRAY:

Well, they were, of course, people that I'd seen in my childhood, so it was a thrill to share the screen with them. I really, really enjoyed being with them. More of my scenes were with him than with her, but I enjoyed working with them both, greatly. He was marvelous. Of course, he won the Academy Award, playing the drunk in "Lost Weekend." He was a wonderful actor.

PCC:

And then "The Cross and The Switchblade" -- that must have been another passion project for you.

MURRAY:

That was a passion project. And we shot down in Harlem, where people were having trouble shooting. But we didn't have any trouble. There was a man on the set named Tom Harris who worked as a stand-in and he was a former fighter. And a former jailbird, as a matter of fact. He had a religious conversion while he was criminal and he got away from crime and he became a prison chaplain, as a matter of fact. And he kept things quiet on the set there [laughs].

At one point, he took the knife away from a young hoodlum who was hassling some people on the set. He went and he took the knife away from him. So he kept the peace, Tommy Harris. We made a movie about him. ["Confessions of Tom Harris," a.k.a. "Childish Things"]

PCC:

Yes, it's quite compelling. And in "The Cross and the Switchblade," you got a great performance from Erik Estrada.

MURRAY:

Well, thank you. He was a street kid. He actually had a knife scar on his back. Yeah, he was somebody who knew that life of the New York gangs. And I thought he was just magnificent.

PCC:

And that must be another of your films that people say influenced them.

MURRAY:

Yes, that's true. It's been translated into over 30 different languages. And it broke records in many, many theatre houses. But it was never picked up for television and that made me very sad, because I think its influence would have gone much further, had it played on TV. But it didn't.

PCC:

Another film of yours that is played quite often is "Conquest of the Planet of the Apes." Did you enjoy playing a villain?

MURRAY:

Oh, yeah. To me, that was just a little movie that I was making for fun. I had no idea it would turn out to be such a big franchise like that.

PCC:

There's such a social commentary element to that movie.

MURRAY:

[Laughs] Yes, yes. It amazed me how that became so important.

PCC:

That particular film seems to have been the foundation for the current "Apes" franchise.

MURRAY:

Oh, yeah, absolutely.

PCC:

And later "Endless Love," was that a controversial picture at that time?

MURRAY:

Yeah, it was, because of the love scenes between the teenagers, because Brooke Shields was only 15 at the time. She had the nude scene with a guy. So the film got a lot of criticism for that. And when you see it again, I really appreciate it. I thought it was a very well done film, very well directed [by Franco Zeffirelli]. And I thought she was wonderful in movie, as was the boy [Martin Hewitt].

PCC:

And you returned to series television with "Knots Landing." Were those seasons enjoyable for you?

MURRAY:

Yeah. I asked to be written out of it after two-and-a-half years, because I wanted to do my own series. And CBS bought my own series, but they never filmed it. So that turned out to be a very unfortunate move of my own, because I loved working with those people -- Michele Lee and the writer-producer David Jacobs and the rest of cast. I loved working with them. And it was a shame. That's something I've always regretted, that I ended that experience. That was one of the best of my life.

PCC:

More recently, what was the experience like, working with David Lynch on "Twin Peaks"?

MURRAY:

Oh, boy [chuckles]. David Lynch -- Wow! What a pleasure that was. That came as a total surprise to have David Lynch call me, at this time of my career, at this age, to play a major role in a David Lynch film, that was something. That was quite an honor. And my son Michael, who is also an actor [a.k.a Mick Murray, appeared in Woody Allen's "Radio Days" and TV's "Cop Rock, "Melrose Place," "Beverly Hills 90210" and "Angel"], he drove me down to the set from Santa Barbara every day. I commuted. I didn't stay down there. And we'd run the lines every day. And he'd make me run them 10 times each day. And I had 10 days down there, so I ran the lines 100 times [laughs].

And working with David Lynch is wonderful, because he's very appreciative of your work. And he creates such a creative atmosphere that it's very, very exciting.

It's interesting to watch that film, because it's almost like two different movies. There's a movie that is "Twin Peaks," which is all these weird characters and these strange things happening, strange supernatural things happening. And then the part I was in was like a straight, realistic story. It's just like two different films. So it was fascinating to see what David Lynch did.

And he's marvelous in the way he treats people. Whenever somebody's finished with their work, he stops production and gathers the cast and crew around and says, "Miss So-and-So is finished today and let's give her a nice hand." And everybody would applaud. And he would do that for even small characters. He's very, very considerate, one of the most considerate men I've ever worked with.

And also one of the most imaginative. His concepts, I'm just awed by what David Lynch does. I feel so lucky to have this opportunity at this time in my life.

PCC:

You mentioned your son, I guess several of your children are involved in the arts?

MURRAY:

Yeah, my older son Christopher is an actor. And he had a series for a while called "Zoey" [The Nickelodeon show "Zoey 101"]. And he was in a marvelous movie with Sean Connery ["Just Cause"], he had a leading role in that. And we did a movie together, called "Breathe," that my two sons were in. It's an underwater movie.

PCC:

Has that been released yet?

MURRAY:

No, we don't have a distributor as yet.

PCC:

I saw on your list of credits a movie called "Elvis is Alive," which mentions your son Sean doing the score. [Sean Murray has composed music for numerous films, TV projects and video games, including "Deep Blue Sea 2" and "Earthstorm," as well as "Call of Duty: Black Ops"]

MURRAY:

Actually, that movie was never made. That screenplay was sold, but it was never filmed.

PCC:

So "Breathe" is the one to watch for.

MURRAY:

Yes. And Sean does the music for that one, too. And Michael has a major role in it. And he actually wrote the screenplay, as well.

PCC:

And you and Bettie have been married for well over 50 years?

MURRAY:

Yeah, we got married in 1962 in Berlin.

PCC:

And your secret for maintaining a successful marriage, whilst being in the business?

MURRAY:

[Chuckles] I would have to say the main thing, of course, is simple fidelity. And it helps to be married to somebody who's a great human being and a great beauty, so you're not very tempted to get involved with anyone else.

PCC:

What aspect of your career is the greatest source of pride for you?

MURRAY:

I think the "Hoodlum Priest," probably.

PCC:

Looking back, any regrets?

MURRAY:

No, not really, because everything that I turned down, I did something that wouldn't have been, had I done the thing that I turned down. So I'm very happy with my decisions.

PCC:

You certainly followed your own path, never wavering from your sense of values. Do you think that made the career more challenging in some ways?

MURRAY:

It might have. But I think it was more of a help than a hindrance, because if you are passionate about your work, that's always good.

PCC:

What do you view as being your legacy in film?

MURRAY:

[Laughs] I don't really think about a legacy. I'm just pleased that the films have received good critical notice and also, most of them were successful with the audience. So I'm just happy about that.

|