|

PCC'S CHAT WITH THE "CZAR OF NOIR" Non-Fiction Author, Novelist, Festival Programmer, Founder of the Film Noir Foundation And Host of TCM's "Noir Alley" By Paul Freeman [June 2023 Interview]

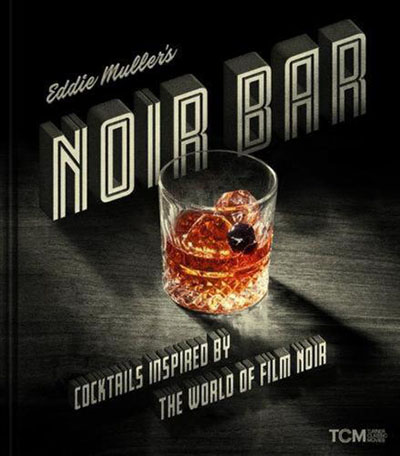

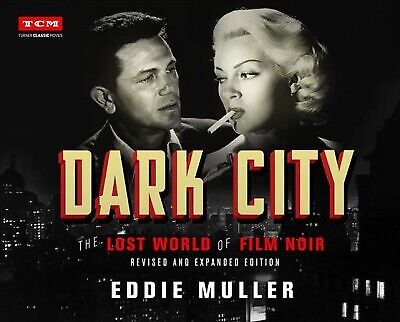

Don't worry. Eddie Muller's got you covered. His latest book, "Eddie Muller's Noir Bar: Cocktails Inspired by the World of Film Noir," [Running Press] will introduce you to luscious libations sure to make you forget your troubles... and to remember some great vintage films and stars. You'll imagine yourself as a tough guy or a dazzling dame as you sip the smooth cocktails Muller has paired with 50 gritty movies. He tells you how to stock your bar. Muller even gives the reader a rundown of the tools of the trade, so you'll have everything you need to be a proficient mixologist. Without his input, you might have neglected to have a julep strainer on hand. And are you certain you know how to properly chill, stir, shake and garnish? Muller clarifies the appropriate methodology. Throughout the book, he includes intriguing bits of trivia about the films and the drinks, as well as personal recollections. The book also features fantastic movie photos and poster art, as well as seductive shots of the cocktails themselves. Thus there's a glamorous, stylish sheen to our dive into the seamy side of life. Among the many familiar faces who pop up on these pages are Barbara Stanwyck, Rita Hayworth, Alan Ladd, Veronica Lake, Ida Lupino, Robert Ryan, Mary Astor and Joan Crawford, to name a few. What was director Sam Fuller's favorite drink? You'll find out here, as Muller serves up a wealth of tasty trivia. Paying tribute to his favorite film, the Humphrey Bogart/Gloria Grahame picture "In a Lonely Place," Muller provides one of the simplest recipes, the Horse's Neck, which contains bourbon or rye, ginger ale and, as a garnish, a lemon peel spiral. He adds notes and pro tips to help you make the drink special. You might write the great American novel after downing the Hemingway Daiquiri, an homage to 1950's "The Breaking Point," which stars John Garfield. If you were entranced by "Nightmare Alley," be sure to whip up a "Zeena," named for Joan Blondell's character. Of course, if you bolt down too many of these, you could wind up a carnival geek like Tyrone Power's Stanton Carlisle. When you crave another jolt from the dark side, tune in to TCM's "Noir Alley." Muller, the learned and amiable host, gives viewers fascinating facts about the films he features each week. Some of the movies are classics; others obscure, but worthy of attention. His sharp wit, casual charm and seemingly infinite reservoir of information make the show a must-see for film fans. He puts a spotlight not only on the actors and directors, but the cinematographers, composers and others the public may not be so familiar with, but who played vital parts in giving these movies a lasting impact. That gives the audience more to pay attention to, especially on second or third viewings. Temptation, crimes, betrayal -- you won't find characters like Andy Hardy in the noir sphere. The rain-slicked streets of the genre are trodden by lost souls, those who are damned, though they may not realize it yet. However, those sitting in front of their screens, watching the sordid stories unfold, needn't wallow in despair. With Muller as a guide, your trip into the underbelly is sure to be not only memorable, but fun. He's the son of the legendary sportswriter also named Eddie Muller, who, during his 52-year stint with the San Francisco Examiner, gained the monicker "Mr. Boxing." The younger Muller thrived in that environment. By his teens, he was hooked on film noir. For Muller, noir grew from being simply a fascination to a quest. Muller resolved to bring more attention to these films and to save some from disappearing altogether. His devotion to the genre has made him one of the world's leading experts on the subject. Muller's work as an author includes novels, such as the award-winning The Distance, and several acclaimed non-fiction books, such as Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir. His Noir City film festival has, for years, presented noir treasures to new audiences. Muller founded and continues to head the Film Noir Foundation, As stated on the website's home page (http://www.filmnoirfoundation.org/index.html), the organization is "dedicated to rescuing and restoring America's noir heritage." We're grateful that Muller found time to talk with Pop Culture Classics about his many pursuits.

POP CULTURE CLASSICS: EDDIE MULLER: So when I'm putting the book together, people would always say, "What was your inspiration?" My inspiration is finding a photograph from the movie and they're actually drinking. And it's like, "Oh, good, I can use this picture." So that made the cut instantly, if I could find a visual reference of people drinking in these bars. That was a biggie, you know? PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: And I thought this would be interesting, by virtue of the fact that it's called "The Crimson Kimono." That already sounds like a cocktail to me. And because it was a multicultural story, I said, "We can do something with Japanese whisky here, to kind of tie it into the movie." Then it just becomes the challenge of, "Well what would make sense in this drink?" And of course crimson would be like a Compari or something. And then more of the Asian influence would be like a ginger liqueur. And that was kind of how I went about. And the same thing when I did a drink from "The Lady From Shanghai." It was like, "Well, how weird is it that Orson Welles is playing an Irishman with a really, really lame brogue." So I said, "Well, I've got to have Irish whiskey." And then I just started thinking, "What would all the other characters drink?" And then you just experiment. And you just put the stuff together and, when it works, it works. And you go, "Oh, I'd actually drink this." I'm also a huge fan of Belita [British Olympic figure skater, dancer and actress]. I think she probably made like six movies total or something and four of them were film noir. So she's like a personal favorite of mine -- "The Ice Queen of Noir." So I said, "Well, I've got to make a frozen cocktail for Belita. It has to be frozen. And it has to somehow be blue, to look like ice, like a skating rink." And because she's British, I said, "Okay, I'm going to make gin the base spirit, because that's very British." And then you just play around with it until you come up with something that you'd actually want to drink. PCC: MULLER: So that was a lot of fun, just searching those out. And there's a great website -- I should give credit where credit is due -- it's EUVS Vintage Cocktail Books [https://euvs-vintage-cocktail-books.cld.bz/]. And this was an invaluable resource. You just go to the landing page and it's like a grid and each square is a cocktail book all the way back to the 1870s. Who collected all of these? They scanned each book and put them into a PDF form that you can just flip through. It's fantastic. You'll find recipes from all over the world. So that was an invaluable reference. That's how I found like the Lee Tracy cocktail. I browsed through this website and then I'd see like a cocktail book from Hollywood in 1934 and say, "That's interesting." I just did a lot of browsing and found recipes, made the cocktail and if the cocktail was good, it was a candidate for inclusion. PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: But I do get that a lot from people who say, "Thanks for the backstory. It made the movie so much more enjoyable." So I appreciate that. And it's not a big deal. I never try to tell people, in my intros, what to think about the movie. If they don't like it, they don't like it. If they love it, they love it. I really just try to provide some kind of context for -- Why did this movie get made? Did these people get along? What was the story behind this movie? I might say, "This movie is known for being one of the first to explore this or that" or something. But if you watch my intros and outros, I'm rarely praising the film unless I think it really deserves praise. I'm just kind of setting it up for people to reach their own conclusions. PCC: MULLER: Number one, I try not to repeat films. But if I do show the same film again, I will go back and look ay my original introduction and try to change it, so that I'm not just repeating the same thing. Because as you know, these days, everything lives on, on the internet. I mean, I think every intro I've done is on YouTube now. And so people can look it up and if I do two intros for "Touch of Evil" or something, they better not be exactly the same. PCC: MULLER: I didn't work in places that were divey or mysterious bars, which is where the noir thing would have come in. I'd be lying, if I didn't say it was like, "Man, I wish I could own my own bar." I would love that. Who knows? Maybe this book will get somebody to invest in a bar. PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: Everything kind of changed during Covid, because we had to shoot everything at home. And then, the fellow who owns the Grand Lake Theatre [in Oakland], where I now shoot a lot of stuff, lives right across the street from me. When I was doing my show from home, he started remodeling his house. And the noise and the sound, I couldn't shoot my show at home. It was just too noisy every day. So I went over to complain to him. And he said, "Why don't you just shoot it in my theatre, since it's Covid time and nobody's coming to the movies anyway?" So that's how that worked out. So that became my secondary set. PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: But yes, you're right, that does happen [laughs], where sometimes I'm like hesitant. I confess, I sometimes go into a bar and I watch the bartender make a few drinks and then, if II don't trust them, I'll order a beer or a glass of wine [laughs], if I don't think I'm going to get a satisfying cocktail out of this person. PCC:

MULLER: Like if you go on social media, it just drives me crazy to see people who will post about a movie and say, "This is the best movie ever made and if you don't think so, you're a jerk!" [Laughs] What's the value of that? From the time I started writing about movies, I have always seen my job as trying to encourage people to watch this stuff. That's the job. It's not to tell them what to think about it, necessarily. It's just to encourage them to explore it and maybe some of my enthusiasm will rub off on them. That's the way I think you have to go about this stuff. I just want people to watch. And I think that's why TCM hired me, because they came to my film festival that I was doing and they saw for themselves, "Wow, he's attracting a pretty diverse audience and the people are really into it." My audience skews -- probably TCM won't appreciate my saying this -- but I think my audience skews a lot younger than the average TCM viewer. But also older, because I get emails all the time from people who proudly announce, "I'm 82 years old and I saw this film for the first time in Podunk, Iowa, when I was blah, blah blah." And I love all of that. But I also get an equal amount of mail from much younger people, people who are like 40 years younger than me, who are like, "Thanks for introducing me to this. I had no idea." So I think that's great. And that's also part of the reason why I've written typical -- if you want to call them that -- film books. But this book is a little different, because I'm hoping that people who are young and into cocktails and all that stuff will see this and, who knows, maybe they don't watch old black-and-white movies, but maybe this will lead them into that. I know that TCM hired me because, at one point, just talking to some people who worked with TCM, they said, "So you can really do this and all you focus on is film noir?" And I said, "Well, you know, film noir is the gateway drug to classic cinema, because kids will watch a film noir, where they won't watch a western or a screwball comedy or, God forbid, a silent movie. So if you can hook 'em with film noir, then once they get used to it, I think they'll expand their viewing to include a lot of other great stuff." That's what I see as my job, is convincing people that there's eternal value in these films. PCC: MULLER: Then I learned that a lot of these films were independently made and they had a distribution deal with the studio. But the studio didn't own the movie. And the studio may not have even produced the movie. So now all these film preservationists and restorationists call these movies "orphans," because they don't have a parent. It's like Dick Powell made "Cry Danger" and it was released by RKO. But it's not an RKO film. It was financed by two guys from Omaha that Dick Powell talked out of their money, so he could make an independent film. And then when that distribution deal lapsed, nobody was quite sure who owned the movie. And those are the films that I tend to go after, where they've slipped through the cracks for various business reasons really. And then to your point, Paul, what became really interesting was I started realizing that I had better luck finding missing movies in film archives overseas than I had finding them in the States, because overseas they weren't as quick to to junk stuff as they were in this country, where it's like, "Well, we don't own that, so why do we have it here? Throw it away." That's the attitude in a lot of American studios and archives, right? In some ways, it's just by luck that some of these movies that I've restored, that we've recovered them. Have you ever seen "Woman on the Run" with Ann Sheridan? PCC: MULLER: So we just had to sign a letter of indemnity that said if the people who own the movie today resurface and demand money, they're going to demand it from me and not from Universal. I said, "I'll take that bet." And then we were eventually able to restore that film, which Universal didn't own. The British Film Institute has been a huge benefit to me, because London is where American studios would send their movies to be distributed in Europe. They'd send them to London and then prints would be made and then, depending on where they were going, they would ship them the stuff that would be like dupe negatives and stuff, so that subtitles could be put on in the various markets. So like a movie going to France or Berlin would go through London. And so a lot of those films would remain at the British Film Archive, but the BFI, their charter is to restore and preserve only British films. So if I find a movie there that is an American film, they'll just send me whatever material they have on it, just as like an archive to archive kind of thing. And then we can restore it. So that's what happened with "Woman on the Run." They actually had a dupe negative in the archive that we were able to use as the basis for restoring that movie... That's a way longer answer than you were expecting. PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: I have great cinephile colleagues in France and when I would email and say, "What do you think of this movie?" like "La Bestia Debe Morir," "The Beast Must Die." And they say, "What is that? That's the Claude Chabrol movie, right?" And I'd say, "No, no, no. It was made in 1952 in Argentina, 17 years before Chabrol made his version of it in France." And literally no one had heard of the movie. And so that is incredibly gratifying, to give a film not only a new lease on life, but honestly, like a first lease on life, because these movies hadn't been seen in 60 years. PCC: MULLER: There's a couple of unusual films that were made in Mexico in the 1950s where like Jack Palance would go to Mexico to make a movie and it doesn't really feel like a full-blown noir, but the writer and the director and a couple of the actors... It's like, "We may want to check this out and look into restoring this film." That happens a lot. PCC: MULLER: And I think it happened because artists were -- I don't want to say fed up -- but they had spent so much time writing a certain kind of uplifting story, because their job was to get America through the Depression and then get America through World War II. And in some ways, it's very ironic that the artistic reward for having done hat job and done it well was that now, in 1946, they could start telling uglier stories that didn't have to end well. There was no edict anymore that it has to end well. And I think it was just artists, being contrarians by nature, at least the ones who wrote this kind of stuff, were saying, "Yeah, I've always wanted to do a story where the protagonists are the bad guys." That's really why "Double Indemnity" was such an influential and subversive movie, is because it took a couple of really popular movie stars and made them the villains. And that was not a common thing in Hollywood at the time. And to me, that's always been one of my essential aspects of noir, is that it's asking the audience to empathize with people who are doing the wrong thing. You know they're going to get their comeuppance and all that, but at least you get to spend 90 minutes watching that happen. To me, that's kind of what sets noir apart. It's a crime story and the truly noir ones are told from the criminal's point of view. That's like "The Killers." Or you get a movie like "Touch of Evil," where the villain is the cop. That's a very different approach to the story. I think that's really what it was for me. And, of course, in post-war Hollywood, because of what was happening with the beginnings of the anti-communist witch hunt and everything, there was a sense of paranoia that was taking over the business that I think also had a certain amount of influence on what people were writing, like stories where you can't trust anybody and you don't know who's your friend and everybody's out to get you. I think that was the pervasive mood in Hollywood in the late 40s and early 50s. So it found its way into crime stories, because you couldn't really make a flat-out political statement at that time. But if you wove it into a crime story, you could get away with it. PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: Interestingly, invariably, when I talk about the political climate at the time these films were made, I do get backlash from people who say, "Stop talking about the politics. They're just movies. We don't want to hear about the politics," which I think is just complete bullshit. Because you need to know this is what was happening. If you wonder why Abraham Polonsky made only two movies and then never made another movie for 18 years, here's the reason why [the Oscar-nominated writer/director was blacklisted]. It's weird. I don't know what to tell you about the culture at large, like why superhero movies run the business now. Like what does that say about America, that the comic books that I read as a child 50 years ago are now the bedrock of the entertainment industry? That's confounding to me and I don't know what that says about the culture. It doesn't say anything too good, as far as I'm concerned. But that's just the way it goes. PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: PCC: MULLER: And then the guy who was in charge, the executive director of the foundation, met me and we just started talking and I said, "Oh, I'm a cat guy." And this is so funny, because, usually, when you start talking about your pets, people's eyes glaze over and they're like, "Oh, shit, he's going to show me pictures now. Oh, my God." But I did that with this guy and he was like, "Wow, you really love animals. You should be on the board." And I said, "I'd be honored." And the next thing you know, I am on the board. That's pretty cool. PCC: MULLER: So I was approached with the idea of doing this and I said, "As long as it's in black and white, then I'll do that, because it is part of my mission to convince younger people to watch these films. It felt like if we did a book like this in black and white, then when kids see the movie, they'll get it. It'll resonate with them. Like, "Oh, this is like the book that I liked when I was a kid." I'm sure that you have favorite children's books that you remember fondly. Scuppers The Sailor Dog was the favorite of mine, when I was a kid. That was a dog who's a sailor who shipwrecks on an island and builds himself a lean-to to survive and all this stuff. I loved that book. And so I felt like, if I could write one of those that somehow connected to the movies, that'd be pretty cool. PCC: MULLER: PCC: For more information on Eddie Muller's many projects, visit http://eddiemuller.com/ |