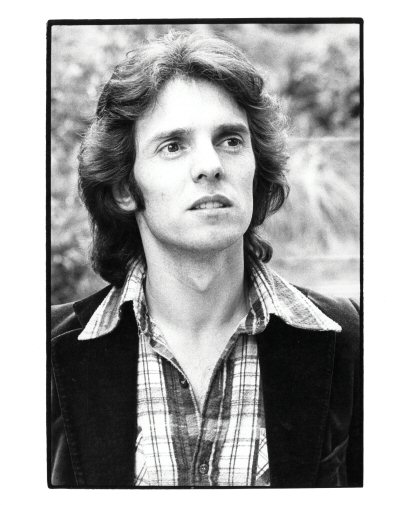

IAIN MATTHEWS: OF ART, OBSCURITY AND LASTING MUSICAL MARVELS

When I joined Fairport, I was already listening to Tim Hardin and Tim Buckley. But they certainly turned me on to a lot of people that I wasn’t aware of. I hadn’t really listened to Leonard Cohen at that point. And I certainly hadn’t bothered very much with Dylan. I was more familiar with cover versions of Dylan songs than the man himself. And Richard Farina, I think Richard Farina was the big one that they, Fairport, turned me on to. I’ve since recorded four or five of his songs. Currently, along with a couple of the guys from Plainsong, I’m working on an album of Richard Farina songs for release later this year. PCC: When you first got together with Fairport, was there a sense that there was some extraordinary music to be made with this group of musicians? Or was it just another opportunity, another band at the time? MATTHEWS: I think it was an opportunity. I liked what they were doing. But no one really had any idea where it was going. When I joined the band, no one was writing. The writing really began in the few months following me joining the band. Richard began to write a couple of things and Ashley [Hutchings], the bass player. But primarily they were doing a lot of that West Coast stuff that we take for granted these days. PCC: What was Richard like as a creative collaborator for you? MATTHEWS: My collaborations with Richard back then were pretty brief. We only really co-wrote one song per album. And it was both times, a lyric that I had written, that I’d taken to him. I think the second song was the lyric and a fragment of a melody. And he basically wrote the song around the lyrics that I took him. PCC: What sort of impression did he make on you as an artist? MATTHEWS: Well, Richard taught me to play guitar. He showed me the basics of playing guitar. I think it’s more in retrospect than it was at the time, looking back and listening to his guitar playing, I don’t know if you’ve seen that black-and-white movie that was filmed in France, where we do “Reno, Nevada,” [a Richard Farina song] - it’s been floating around a long time. I go back and I look at that and I listen to that solo and I think, “My God! This guy was 19 years old, when he played that solo.” And there’s no wonder that Clapton cites him as one of his favorite guitar players. I mean, it’s just been there, staring everyone in the face for such a long time. And seeing him perform in recent years, acoustically, he is just a stunning performer. Truly amazing stuff. PCC: And Sandy Denny - what did you see as being her special magic as a vocalist, her uniqueness? MATTHEWS: Sandy’s uniqueness and Sandy’s input certainly turned the band’s direction around. I think, after Sandy joined the band, they really began to heavily embrace that English traditional ballad mixed with whatever it was they were doing. I really don’t know what you’d call it. I guess, if anything, they were an electric folk band. But that doesn’t do them justice, really. After Sandy joined the band, they really began to swerve off in that direction, abandoning the stuff that I was getting into. And the things that they had turned me onto, they just completely left it behind and went off in this electric trad direction. So, yeah, she really changed the attitude of the band, when she joined. And it didn’t take long. I think we were in the band for six months together, before I left. PCC: And as far as the allure of her vocals? MATTHEWS: Well, it’s out there to be witnessed. It’s out there to be experienced. There’s just no two ways about it. PCC: You did a Sandy Denny tribute album [“Secrets All Told”]? MATTHEWS: Yeah, how do you know about that? I did it with a friend of mine in Philadelphia, Jim Fogarty. And I think Jimmy is the only one who still has copies of it. It’s a lovely album. It was Jim and his wife Lindsay and a fretless bass player friend of ours [Walt Rich]. And we just decided that we wanted to pay homage to Sandy and her songs. And yeah, we made an entire album. The band’s called No Grey Faith, which is an anagram of Fotheringay [the name of the folk-rock group Denny formed, when she left Fairport Convention]. PCC: Folk-rock was very much in its infancy, when Fairport came to the fore. It became so influential. Did that surprise you, that the band had such an impact, long-term? MATTHEWS: Yeah, there was a period where I really liked what Fairport were doing. I’m really not so keen on what they ultimately became. They influenced a lot of people and they really created a niche for themselves in the history of music, really. But for me, they’ve just become a little bit too much of a jigs-and-reels band now. There was a period - you know the album “Full House”? That was the one they made after Sandy left, where they became a boy band for a while. [Laughs] I think that’s my favorite record. I think were heading in that direction, even with Sandy. But, for me, they really hit something, when they made that album. PCC: So was it a question of wanting different directions that led to your leaving the band? MATTHEWS: Yeah, exactly. I wanted to embrace more of a contemporary American singer-songwriter attitude and they wanted to do go deeper into the English traditional catalogue. PCC: So as far as the impetus for forming Matthews Southern Comfort, was that a desire to head wherever you wanted creatively, without debate? MATTHEWS: Yeah, exactly. I wanted to pursue what I’d been pursuing with Fairport, except this time, I could do it more on my own terms. I could call the shots. So I started my own band. PCC: Did you expand the writing at that point? MATTHEWS: I did, a little bit, yeah. By then, I was playing a bit of guitar and yeah, trying to find myself as a writer. I don’t know if you ever truly find yourself as a writer. I think you develop into something, but I still don’t think I’ve really found myself as a writer. But , yeah, I started writing a little more in that period. PCC: Are you comfortable now with that idea that finding your identity as a writer is a constant search? Are you at ease with that? MATTHEWS: Well, I’ve always been at ease with it. It’s never frustrated me. I’ve always tried to keep myself in the moment and accept whatever comes my way. It’s the same with songwriting. I guess you can push it, but I’ve always just tried to let it flow and just accept whatever happens. PCC: Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock,” how did that song make its way to you? MATTHEWS: I found it on her album. I bought her album. We were doing a BBC session and they wanted us to record five songs and I think we only had three or four. And I presented it to the band and we worked up an arrangement and recorded it for the BBC. And there was such a heavy response to it, when they aired it, that the label asked us if we’d go back in and record it for a single. So it just happened. I wasn’t particularly searching for a Joni song. I was just searching for a good song that we could represent. PCC: It was so successful, was there any temptation to chase that same kind of success? Or pressure from the record company to try to do something similar? MATTHEWS: Not really. All the baggage that comes with having a hit record came very quickly and I wasn’t very prepared for all that stuff. I was doing it for the song, for the music. And I left the band while the single was still in the Top 10. PCC: Because of that baggage? MATTHEWS: Yeah, because of all that other stuff. I just saw everything else as a distraction, taking me away from creating music. And my way of dealing with it was to just turn my back on it and try and start again. PCC: You were never one to pursue the mass audience. You just wanted to do music you believed in.

Exactly. It’s just never in mind that a particular song could be successful. I mean, I’m grateful for it, because each time that has happened, it’s prolonged my career for another 10 years. And it gives people reference points, when they talk to you. But it’s never been something that I was looking for. PCC: You have a legion of fervent fans and you’ve always had the critical acclaim, but generally, not the mainstream commercial success. That hasn’t been frustrating then? MATTHEWS: No, it’s a blessing, because it just means I can get on with it. [Laughs] PCC: What went into the decision to move to L.A.? MATTHEWS: We’d handed in the second Plainsong album and Jac Holzman [Elektra head] didn’t like it. And at that point, when he told me he didn’t like it, he also said that he would like me to consider going solo again. And he had an idea to team me up with a producer in Los Angeles and wanted to know if I was open to the idea. And he told me it was Michael Nesmith. And would I consider going into L.A. and meeting with Michael and talking about making a record? And it all just kind of fell into place. Michael and I got on great. I consequently came to L.A. to make the record. I decided I was going to stay six months and make the album, see it come out, do some press and then go back. And I never went back. I stayed 28 years. PCC: Had you already been familiar with Michael’s work, beyond The Monkees? MATTHEWS: Yeah, I wasn’t familiar with his Monkees stuff. I knew the obvious things. I knew the hits. But I was a lot more familiar with his First National Band stuff. PCC: And what were the things you admired about him, once you got to know him and work with him? MATTHEWS: He was a man of integrity. And he was doing it for the music. Michael was never - or never appeared to be - interested in trying to score hits. I think, in the beginning, with The Monkees, by the stories he told me, he was just doing it to have fun. He made a lot money with The Monkees, but he also lost all that money. By the time he was doing those First National Band things, he was just one of the boys again. And he was in it 100 percent for the music. And I think that’s why we hit it off so well. PCC: In that period, you were making a lot of great music. What went into the decision to go into A&R? MATTHEWS: Well, that’s a little later on. I came to L.A. in ‘73 and I moved into A&R in ‘84. So it’s a bit later on. I’d made an album called “Shook.” And when it came out, I listened to it one day and I thought, “I don’t like this record very much. Who is this guy? What is this music he’s making? It doesn’t mean very much to me.” And the more I thought about it, the more I thought that I was being guided, rather than finding my own direction. And at that point, I felt that I needed to stop and think about things. But I didn’t want to leave music. I wanted to still be involved in music. And there was a friend of mine here in Los Angeles, who ran the publishing for Island Records. And I went to talk to him about it, just friend against friend. And he said, “Well, why don’t you come and work for me? We’re doing well here and what we need next is some kind of A&R presence. I’d like to be able to sign acts for the label.” And I said, “Okay, I’d love to.” He gave me a job and I worked for him for about a year-and-a-half. And then I had an offer from Windham Hill, who was starting a vocal label. And that seemed more to my taste than looking for bands for Island. And I went over to Windham Hill for another year. So it was about two-and-a-half years I spent in A&R. PCC: And did you find that satisfying in its own way? MATTHEWS: I found it satisfying. I found it frustrating, also. I think, once you’re an artist, it’s very hard to shake the artist attitude and put yourself on the other side of the table. I realized, at that point, when I was trying to guide other acts into avoiding all the little pitfalls that I’d encountered along the way, that you can’t do that. I think artists are intent on making the mistakes, so that they can learn by them. And I found that part of it a little frustrating, but understandable at the same time. And as I was dealing with all that company policy and A&R tactics, slowly the muse began to return. And I started feeling like writing again. Possibly performing. I had a concept and I presented this concept to Windham Hill and they turned it down flat. And I thought, “Well, I believe in this concept and somebody’s going to do it, so it might as well be me.” So I quit my job and focused on this concept. And, ironically enough, the first people I took it to were Windham Hill and they said, “Yeah! We like this!” [Laughs] PCC: Was this a different division of the company? MATTHEWS: No, exactly the same people. When I presented it as a concept, they didn’t get it. When I showed it to them as a body of music, they got it. PCC: And what was this project? MATTHEWS: Well, the basic concept was to take a songwriter, a relatively unknown songwriter, and interpret his songs or her songs in a different way to the way the songwriter would have presented them. And my way was to a degree, to embrace that sort of New Age thing that was happening in the late 80s with synthesizer - it’s kind of hard to describe. Do you know the album, “Walking A Changing Line”? [1988] It came out on Windham Hill. And I chose Jules Shear as the songwriter. And I did an entire album of Jules Shear songs. And I tried to use a different keyboard player on each track. A guy called Patrick O’Hearn is on one. He was making records at Private Music. I used Van Dyke Parks on one. I tried to vary the style of each track, but keep it within a certain genre. And I think ultimately, it worked out very well. It was a very popular album within a certain circle. Of course, my “Valley Hi” [1973 Elektra] friends didn’t really embrace it [laughs]. PCC: And at that point, your days as a record executive were over? MATTHEWS: I was done with it, yeah. I’d had a taste of it. And it wasn’t something that I wanted to pursue for the rest of my career. And the muse came back. I played the Fairport festival, Cropredy, in ‘87. I was backstage and Robert Plant was playing the festival, too. And Robert took me aside and he said, “Listen, man, this ain’t our thing. It’s not for you. You need to really get back on the horse that threw you and start performing again, start writing again. There’s a lot of people out there that still want to hear what you have to say and I’m one of those and I strongly suggest that you take my advice.” [Laughs] PCC: So that really had an impact on you. MATTHEWS: Yeah, I took it to heart. I did. I thought, “Well, if Robert feels that way, there’s probably a few more out there that feel the same way.” PCC: In the years since then, you’ve had so many interesting collaborations - Egbert Derix, The Searing Quartet, the revival of Matthews Southern Comfort, Plainsong - do you really crave that kind of diversity, a wide creative latitude with different musicians? MATTHEWS: I do, yeah. I might have mixed it up a little too much in certain period. But I do like to have that diversity. I like to play solo. My favorite way to play is with Egbert. I love doing the duo stuff with Egbert. But I like experimenting with different combinations of people. You know, I had the trio with Eliza Gilkyson and the Dutch songwriter, Ad Vanderveen [called More Than a Song, the trio released two albums]. Yeah, I don’t like to get bogged down in any one thing. I like to try and move around. There’s always a core sound to what I do. I think the songwriting binds it all together. PCC: Did you enjoy exploring more of jazz direction with the Searing Quartet? MATTHEWS: Yeah, I’ve wanted to do that for a long, long time. I’ve had a couple of opportunities, but it never quite panned out. When I met Egbert, it was obvious - “This is the moment, this is when you’re going to be able to do that and explore the jazzy aspect of things.” And we became songwriting partners, too, which was really the kernel of what we were able to do. It was all based around the songs we wrote together. PCC: After living in Austin, as well as L.A. and England, what has made Holland the ideal place for you now?

There was a point, I was living in Texas, and I just began to dislike Texas. I found the weather very oppressive... And I didn’t really work very much in Texas, so I was always a long way from anywhere that I toured. My music was beginning to have a little resurgence in Europe and I thought, “Well, maybe this is the time to learn to become European again. It’s time to go home.” A friend of mine had a big apartment in Amsterdam. She was my publisher, actually. And she said, “Well, the top floor is empty. It’s waiting for someone to live in it. Why don’t you take that until you find your bearings?” That was the opportunity I was looking for to go back. I went back, spent a year in Amsterdam, started touring again. I went down south and met someone. Within a couple of years, I was married [to Marly]. And I have two girls [Madelief and Luca]. PCC: So now you’re in a more rural area? MATTHEWS: Yeah, it’s a lot more rural. It’s down near the German border. I’m twice as close to Cologne as I am to Amsterdam, really. It’s beautiful down there. It’s peaceful. I’m in a small community - big village, small town. PCC: Sounds like a good atmosphere for creativity. MATTHEWS: It is. PCC: So at this point, what are the greatest rewards and the greatest challenges of your life in music? MATTHEWS: Well, I think the great reward is that I’m still doing it now. I think about it almost every day, the fact that I’m still doing it. I'm still able to come over to the States and tour. Still able to record and write. I think the challenge is just to get better. It’s never too late to get better. Egbert pushes me - with the songwriting. He pushes me to be a better vocalist. And to move in different places than I have previously. Yeah, I just want to keep improving, see how far I can push myself. PCC: And do you think about what you might want your musical legacy to be? MATTHEWS: No, not really. [Laughs] I just leave that for other people. You now, I’ve got my body of work behind me. And that’s really enough for me. For the latest news on this extraordinary artist, visit iainmatthews.nl. |