|

JOHN BELAND: HIS GUITAR GAVE HIM THE “BEST SEAT IN THE HOUSE” TO WATCH THE HISTORY OF COUNTRY-ROCK UNFOLD

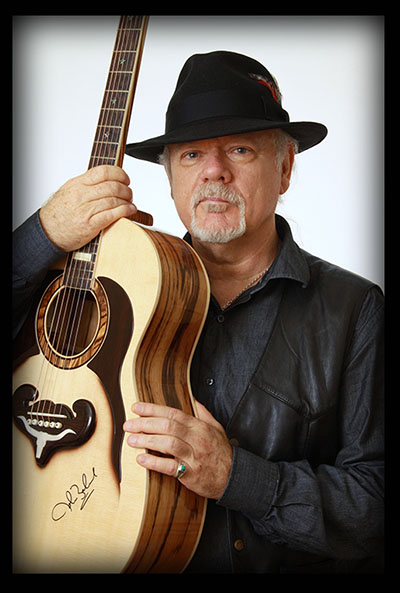

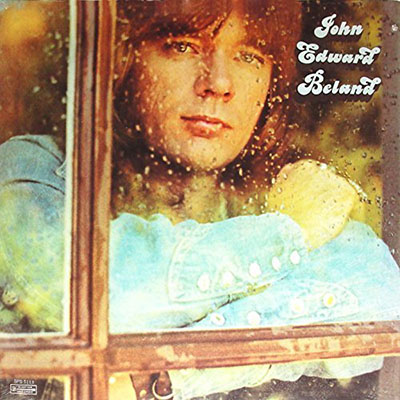

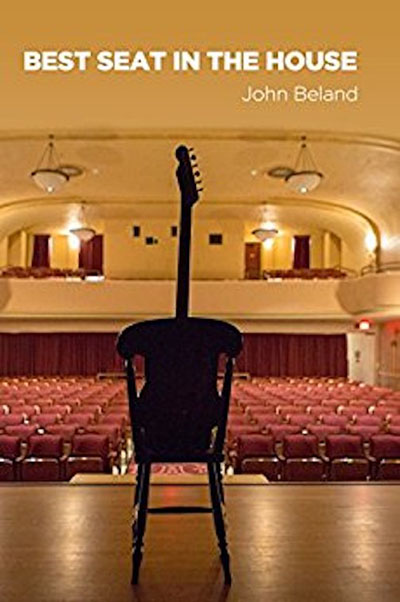

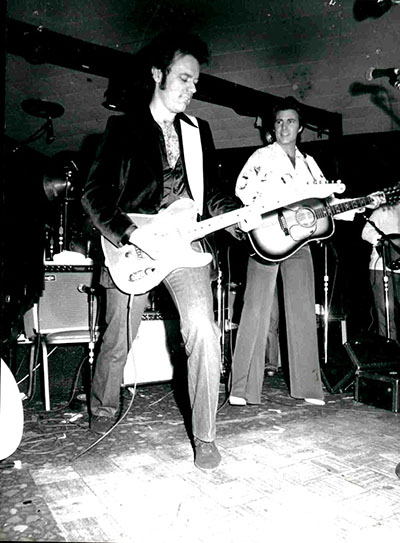

By Paul Freeman [May 2018 Interview] You gotta be good to be lucky. John Beland is clearly both. At age 17, packing only a shiny dream and the $20 he had swiped from his dad’s wallet, Beland ran away to Hollywood. He was determined to parlay his talents as a guitarist, singer and songwriter into a career in the mad and magical world of rock ’n’ roll. Fortunately, this didn’t turn out to be a cautionary tale. Beland succeeded, beyond anything he had imagined while growing up in Hometown, Illinois. He became one of the top session musicians in L.A. and later Nashville. He became a prominent songwriter and producer. And he became an integral part of the bands of such greats as Rick Nelson, Linda Ronstadt, Kris Kristofferson, Dolly Parton and Arlo Guthrie. In the process, Beland helped to shape a new musical form — country-rock. His band Swampwater, formed to back Ronstadt in her barefoot days, released two albums of their own. They were among the pioneers of the genre. Johnny Tillotson, The Bellamy Brothers, Mac Davis and Garth Brooks were among other acts that made good use of Beland’s fantastic guitar work. As a member of The Flying Burrito Brothers, Beland penned many of the group’s country hits. Beland also made memorable music as a solo performer. He had a 1969 chart hit with “Baby You Come Rolling Cross My Mind.” He was the last artist to sign with The Beatles’ Apple Records, just before the label imploded. For decades, Beland never stopped being in demand as a musician. He was able to collaborate with many of those he had idolized as kid, including legends like Nelson, Don Everly and Scotty Moore. He had memorable interactions with others, such as B.B. King, Johnny Cash and Buck Owens. He picked up the iconic guitars of Chuck Berry and Roger McGuinn and played those artists’ classic riffs. Beland’s amazing story is now available for all to enjoy. His new memoir, “Best Seat in the House,” recounts the tale of his remarkable career, as well as offering an insider’s fascinating look at the music scene of the 60, 70s and 80s. Filled with the colorful characters Beland encountered along the way, the book has an abundance of inspiring, poignant and funny moments. For so many years, in the studio and on stages across the world, Beland has indeed had the best seat in the house. Now he shares the revelatory view from that perch.

POP CULTURE CLASSICS: JOHN BELAND: PCC: BELAND: And Dan and Lois Dalton were in one of the ensembles of that group. And they had just broken away from that group to start their own production company in Hollywood. That’s when they found me at the Troubadour. So when they took me in, my mom and dad signed the contracts and everything, because I was under age. The Daltons kept a really strong protective watch over me. And for me, it was just an invaluable situation, because they knew everything about the business. And I was like their son, actually. They really treated me like I was one of their own. They taught me everything with regards to publishing, recording, singing… everything. So I was lucky to know the business fairly well by the time I got my first song cut through them, that Engelbert Humperdinck cut. PCC: BELAND: So yeah, it was sad in some cases to see people that I admired and I knew and that I almost worshipped so strongly as a youngster in Hollywood, to know now that maybe their lives went another way. Some of them became alcoholics. Some of them OD’ed. It’s sad to see where their lives ended up, because at the time, when I was 17, I worshipped the ground a lot of these guys walked on. So yeah, it’s a strange situation, writing your own autobiography, because each page takes you back to that time and all of a sudden, all of those people who were so instrumental in your life, they’re there again. And it’s a strange feeling [chuckles]. PCC: BELAND: And I think that’s one of the reasons that I got so much work, as I grew as a musician in Hollywood, because a lot of the stars I worked with, I had really close relationship with, as friends. And I never had to rely on kissing anybody’s ass to keep a job. You know? I knew for one thing, I had the talent. I knew I was good. And I knew I was getting session work and songs recorded and all of that. So that gave me an assurance, in a way, to know that I didn’t have to play any games to keep any gig. And so, yeah, I was really lucky to get started at such a young age and develop that. It sure helped me when, for a lot of other guys in town, with big stars, there’s usually a big entourage and people are sucking up to them and everything. Luckily, I never really had to do that. I really had a close relationship with a lot of the people — they became like brothers and sisters of mine.

PCC: BELAND: And so, at 29, to be sitting in the studio in Nashville, I’m running through the vocals with Don Everly and Sonny Curtis — it was everything I could do to maintain my equilibrium. I used to always think that, when I was in situations like that, that somebody was going to walk in the room and say, “Ah, Beland, you’re going to have to leave.” [Laughs] There were a lot of moments like that in my life — The Beatles and B.B. King and Michael Jackson. And doing sessions for people. And Ricky — he was another idol of mine, growing up. And I became a very, very close friend of Rick’s, besides being instrumental in his later career. So yeah, it was a strange feeling to be singing and all of a sudden, you’re listening to the other guy doing the harmony… and it’s Don Everly. And there’s that Everly Brothers’ sound. And it’s on your record! And you want to run to the nearest phone and call up guys that you grew up with back in Hometown and say, “Hey, listen to this!” It was great. PCC: BELAND: And also working with Linda Ronstadt. That was incredible, because I knew how good we were, when we walked on stage each night. Nobody could follow us, because she was so good. And we had such an energetic show. And a different show, because nobody was really doing what she was doing. And what we were doing. There were moments on stage, in my career, where I would say, “This is like kind of music history going down right here.” And I’m proud of it. I felt that way with Kristofferson, at certain gigs that I did with him. And when I was with The Burritos and we were singing at the Grand Ole Opry for the first time. Or being on “Saturday Night Live.” Or even being out with like Arlo or Johnny Tillotson, people like that, who had such a wealth of history. And they shared that all with me. And you couldn’t put a price on that. PCC: BELAND: The guitar just wrapped itself around me and sucked me in. Once I started getting into playing it, that’s all I could think about. I used to cut pictures out of the Sears catalog and put them in my wallet, take them to school and look at them. So I was really connected to the instrument. And I don’t know why, because nobody in my family was really musically inclined, neither side of my family. PCC:

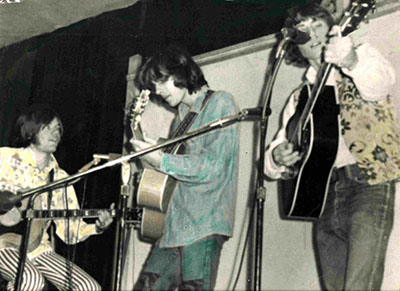

BELAND: I didn’t know what form it would take, whether I would end up a singer or a songwriter or a session musician or even an actor. All I knew was that this was my town. This was ground zero. This was where I was always meant to be. And it made sense to me, that as far back as I could remember, being a little boy, why I connected so much with television or the radio. Whenever things came out, I listened to records in a whole different way growing up, trying to imagine what it was like when they were being recorded. And it all made sense. It kind of all came together in my head, that first day, when I stood there, in the middle of the afternoon, on Sunset Boulevard, in front of Paramount Studios. I said, “This is where I’m going to spend the rest of my life… in whatever capacity.” Yeah, I knew was where I was going to be. PCC: BELAND: And the next day I called them and then I came down and they literally plucked me out of oblivion, because I was right at the edge of it. And I didn’t know what I was going to do. Something inside me told me something would work out, because I’ve always had that little voice. But it was being tested quite a bit by the time the Daltons found me, because I just was totally at the end. They took me in, called my mom and dad, who had the police out looking for me. It was really crazy. My mom and dad were relieved when the Daltons called them. They came to Hollywood. The Daltons told them, “You could take him home, but he’s just going to turn around and run away and come back up here again.” And they said, “There’s something in John that we see and he has a passion for the music in him. And we can see that in him. We’d like to take him under our wings and see what we can do. He can stay with us and we’ll eventually get him some work in the studio and teach him the business and get him an apartment.” Mom and dad, they already had five kids back at home they were trying to figure out what to do with. But they trusted Dan and Lois, to the point where they signed my first publishing and production contract in court. I still have that contract. And we had a little party. Looking back on it, when I was writing the book, I kept thinking, “What were my mom and dad thinking?” Because they had no knowledge of the music business. They didn’t know what any of this was all about. But they trusted Dan and Lois enough to let me pursue it. The other side of the coin would be, I could have been sent into the military, which was during the Vietnam War, a volatile time. And I could easily have ended up on a boat in the Navy somewhere or on a beachhead. But look where I ended up. Talk about luck! PCC: BELAND: And let me tell you, when I got to Hollywood, and Dan and Lois took me in, I studied everything they told me like my life depended on it, to the point where I used to try to dress like the session musicians that I was playing next to. I would watch them and study them and see what guitars they were playing, what shoes they were wearing. If they were drinking coffee, I started drinking coffee. When you’re 18 years old, being on a date with James Burton, your idol… or Hal Blaine or singing on a TV theme song on the Paramount lot — God Almighty! So I never took for granted the opportunities that I got. So I certainly studied it and learned, to the point of the ridiculous. And it sure helped out. PCC: BELAND: But after I sang it, I never watched an entire episode. To this day, I’ve never seen an entire episode of the show. I just didn’t find it that interesting for me. But the process of going out there and singing that song, that was much more important than the show. And then, when it became a big hit, I still didn’t talk much about it or tell anybody about it, because it was considered a cornball thing. Back then, in 1970, you wanted to tell people you were playing with Linda Ronstadt, not singing “The Brady Bunch.” PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: Also, the Monday night hootenannies were used as a showcase for bands that had already formed and wanted to make a splash. They would play for 15 minutes. So I watched Poco, Flying Burrito Brothers and The Carpenters all make their debut there at a Monday night hoot. And I think one of the most important things was, the people that were around me, the kids like myself, that were just trying to get something going, a lot of them were really good. Like Jackson Browne and Glenn Frey and John David Souther — they weren’t just guys waiting to get on stage to sing for 15 minutes. These guys were like Nolan Ryans in the bullpen. It just took a while for them to land something. But eventually they did. But I learned from watching them. I learned to fingerpick. I learned how to structure a song. And singing. Yeah, it was like going to college, going to The Troubadour. And people look back, at that time, at The Troubadour, as the golden years. Those were the years where we all landed there together — Glenn Frey, J.D., Jackson Browne, myself, a lot of guys and girls. And there was an energy there, a camaraderie. And we all got, for the most part, discovered there. So it was kind of like L.A.’s answer to England’s Cavern Club. At the Cavern, you had Gerry & The Pacemakers, The Searchers, all coming out of one club. But something similar happened at The Troubadour, too. So I was there every Monday night, playing for free and backing up people and playing myself and learning. And then I came back to The Troubadour, playing regular weekly runs with big stars. PCC: BELAND: I introduced myself and for a few weeks, we went up and down the coast of California, playing in folk clubs together. Then they became friends of mine, through the 70s. I worked with J.D. on a couple projects. I didn’t work with Glenn, but I saw him all the time. We were always friends. But all of the individual Eagles, individually, I knew they were going to be huge before they started The Eagles. Bernie Leadon played on my first records that Dan and Lois produced. He played banjo. And Randy Meisner was singing with Ricky Nelson. And he was just a great, great singer, a great harmony singer and bass player. When the four of them got together, we heard they were starting this group called The Eagles. And we knew that they were going to be huge… if they got the right song. And they did. All out of The Troubadour. PCC: BELAND: He was dating Linda’s roommate, Brook. So one night he said, “We’re going to a party at Henry Diltz’s house. I’m taking Brook. You can take her roommate.” Well, I didn’t know who that was until I got up there to their house. Right after we knocked on the door, he told me. And I wanted to panic and run back to the car, because I knew about Linda from what I had heard at The Troubadour. And she was pretty hot. And she was like the “It” girl at The Troubadour. But after about five minutes, when I first met her, it was like we’d known each other forever. It was great. We had a great time that night. We went to the party. And it was all terrific. But she wanted to get me to play guitar for her right away, too. And I couldn’t do it, because I was committed to the group I was with. And she just said, “Well, if the group breaks up, call me up.” And when the group did break up, I called her and I ended up starting her first band with her. And it was fabulous. I loved Linda and I still love her. She’s one of the most real and just one of the coolest people I’ve ever known. And I think she’s probably the most exciting singer I’ver ever worked with… or seen. We’d get on stage with just three amplifiers and a drum set and Linda… and a fiddle. And sometimes we’d be opening for people like Vanilla Fudge or The Byrds and these bands with tons and tons of equipment. And there we would be with our little band. And boy, she’d come out in shorts and a T-shirt and just completely knock out the audience. And every gig we did, no matter if it was at The Fillmore or whatever, she was 1,000 percent great. So yeah, it was pretty cool. It all started with a blind date [laughs]. PCC:

BELAND: And then the music, yeah, you get swept up, when the audience is going into a frenzy, and you’re the reason why — it’s an incredible experience. You’re up there actually controlling this audience, who are going absolutely apeshit for her. Yeah, it was a real, real rush, because you knew she was on her way to becoming huge. So every month that we were with her, the gigs got bigger as the energy level got bigger. More press people started showing up at her gigs and the dressing room. So that was pretty exciting to be right in the center of all of that. PCC: BELAND: Also, the other thing that made her extremely special was she was doing this country-rock stuff. We were doing songs like Merle Haggard and Harlan Howard and the hippie audiences that we played for, college kids, they had no idea who those writers were. They were just guys who wrote redneck country tunes. But there was Linda up there on stage, doing “Break My Mind” and Waylon Jennings tunes, “Only Daddy That’ll Walk The Line” and “Silver Threads and Golden Needles.” There wasn’t one act out on the market that did that. So that’s what I think made her so unique. And she did it great. Nobody could touch the way that she did it. And she would get up there and do “I Fall to Pieces” and totally destroy a crowd. They just had never heard anything like her or seen anything like her. She really was her own act. PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: So you had The Everly Brothers and Ricky Nelson, who were considered rock ’n’ roll/pop singers, and there they were spearheading this whole musical movement. Even The Byrds, with their “Sweetheart of the Rodeo” album, that was a pretty radical departure. So yeah, it was a riveting time to be a part of. PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: And John actually was really instrumental in forming The Eagles, because we, Swampwater quit, went from Linda to Arlo — I think Arlo offered us $5 more than Linda was paying, so we jumped ship [laughs]. [Glenn Frey and Don Henley were the first two musicians hired to back Linda, when Swampwater left. Boylan then helped round out the band to support her for a while before they would fly on their own as The Eagles.] PCC: BELAND: And by that time, Linda and her band were partying pretty hard. And I didn’t really feel comfortable being around them, because that band, they all kind of had attitudes and stuff. It wasn’t as fun as it was in 1970 with Linda. The new band, they all took themselves way too seriously. And that wasn’t really what I’m about. I always liked to have an element of having a good time, when I was with an act. And Linda’s thing was just so heavy [chuckles], I guess. PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: But at the time, it just wasn’t commercially accepted. That was the only kind of unfortunate thing about country-rock. All of us, from The Burritos to Poco to us — radio just wasn’t playing it. And college audiences were eating it up. Concerts were sold out and clubs were. But we couldn’t sell records to save our ass. If you look at the history of all those bands out of L.A., other than The Eagles, they were all commercial failures, including the Buffalo Springfield. I don’t know if it was really ever accepted, to be honest with you. It had a cult following. There were a lot of people that really dug it. I guess The Eagles were the only ones that really broke out of that mold. And they had a huge hit and then a few more after that, tons more after that. Pure Prairie League had “Amy.” That did pretty good. But in general, most of the others, like Ian Matthews, Southern Comfort, they didn’t do anything. Yeah, it was a bit frustrating. That was why I left Swampwater, because I didn’t see any financial future in it. And it was frustrating to cut these neat songs and you couldn’t get any airplay. FM radio was brand new and they weren’t even playing a lot of those kinds of album cuts. It was college radio we had to really depend on. But country-rock just wasn’t marketable commodity back in ’69 to ’72. PCC:

BELAND: I loved the challenge of doing an album for, let’s say, Odetta, one night, and then the next night doing a candy bar commercial or playing on various artists’ albums. I mean, I loved it. I loved the fact that it took me all around the world, to Nashville, Memphis, Muscle Shoals, Australia. My session work really was my main ticket. And to this day, I still love it. I still love the process of making a great record, a radio record. And when I hear something on the radio that I played on, it’s really a rush, just as much today as when we did it a long time ago. So yeah, it’s my first passion. PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: When I left Swampwater and did my first solo album, I knew exactly what to do and it was a lot of fun. It validated a lot of things with me. So I was pretty excited about doing that. Producing my own album really got me started on wanting to be a producer. I found that producing, it was like water down a duck’s back for me. I knew what to do. I knew the business of it. I knew the arranging and hiring string players, when there were string sessions. So that was really what I wanted to be. I wanted to be a producer and a session musician. And I really could have done without any of the rest easily. It seemed that I had my finger in a number of pies for a while [laughs]. PCC: BELAND: It broke his heart, when I had to leave him to go with Kristofferson. It was like getting a divorce in a way. It was terrible. But I was Johnny’s music director. The two of us traveled around the world, like a million times, just him and I. He was using pickup bands, musicians in various countries. And I had to work with all of those acts, put them all together for his shows. But basically, it was just he and I against the world. Wherever we would go together, he taught me so much. He was such a wise man. And he was so embedded in country music. He knew the history of country music. He had toured as a kid. He had hit records, played country dates. I couldn’t have asked to be associated with anybody more knowledgable than Tillotson. PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: As a result, a lot of those shows were shitty. Some of them were canceled. Some ended up in riots, because the people in the crowd wanted their money back. And Bobby Neuwirth would edge Kris along. I had to quit. I was getting like an ulcer. It was just like the movie “A Star Is Born,” that movie with Kristofferson, all those scenes backstage. That’s exactly what it was. They were on the road with us, for that movie, at that time right before I left Kris for good. And I didn’t care much for working with Rita Coolidge, one of the few I’d have to say I didn’t quite care for, musically or personally. I thought that she was along for the ride, too. On her own, she never would have been playing those big gigs that we were doing. And I thought, as a duo, they kind of sucked. I mean, Kris could barely sing and she was very low-key. And that’s an understatement. It was like taking a Placidyl, working with Rita, because she’s just so boring. And she was kind of a cold figure. I couldn’t get close to her at all, on a friendship level. When she’d come on the road, they’d argue, get in fights. I’d be on the bandstand, hearing all that shit, going, “Oh, God, I wish I was home.” Yeah, so it was pretty volatile, that year, 1974. PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: They tend to get a little delusional when they get out on the road, playing behind a star. They tend to think they’re right up there with the star. And this was a road band that Mac had and everybody thought they were big rock ’n’ rollers. Anyway, they always had comments about anybody who was anywhere near country. And I was definitely a country session player by that time. In ’77, between gigs with Mac, I was flying to Nashville, doing sessions and working on my album. So I had strong ties. And I caught a lot of flak from Mac’s band about “all that hillbilly shit that you’re playing.” And “You still playing that hillbilly crap?” So I endured it. But then they started saying that about Dolly and she heard comments. So she and I ended up hanging out, just the two of us, on that tour. And we became really close friends. And she knew I wasn’t happy. After the tour, she asked if I’d like to play guitar for her, because she was getting ready to move her whole business out to L.A., management-wise. Actually, I think it was Mac’s manager, Sandy Gallin, who was going to handle it. So I said, “Yeah, great!” And we got to L.A. and I quit Mac and joined Dolly. And she was fabulous, as a person. She’s still one of my dearest friends. I just saw her, about this time last year. I’ve got a radio show that I’m putting together, called “Best Seat in the House.” It’s me interviewing all of the acts that I’ve played for. It’s one on one with each of them and at the end of each show, we do an acoustic song together, one of the songs we did when I was with them. I’ve got okays from just about everybody I’ve worked with — acts that I’ve worked with, famous producers that I’ve worked with and famous musicians and songwriters that I’ve worked with. So there’s a lot of branches on that radio show tree. We’re still trying to decide whether it’s a podcast or something for Sirius or NPR or what might work best. So we needed a pilot show and we did the pilot in Nashville last year. And Dolly was my pilot guest. So we got together again and had a great time doing the show. It was just fabulous to see her. And at the end of that show, we did “Coat of Many Colors.” And it was great. She’s been a great friend of mine ever since I first met her. And she’s done some wonderful things for me. She’s actually been a confidante for me a number of times, when I was going through some rough things with losing my parents and stuff. She’s always called up to see how I was. And I just love her to death. And on stage, she’s flawless. She’s just absolutely perfect. She’s the most technically perfect singer I think I’ve ever worked with. Linda is, too. But Dolly is spot-on. There’s no way she could ever sing a bad note. And she’s gracious to fans and she puts on a terrific show. And she made a real bold, when she moved her career towards more mainstream. And it worked for her. So she’s a wonderful girl and I just love her to death. I can’t say enough about her. It was really special to have her as the first guest on the radio show. PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: And then I’ll be doing a week, possibly two weeks in England in October. And I just finished playing New York last month. I played the Players Club in Manhattan. That was the book launch. And that was a fabulous night. Everybody came out, the governor and all these people. It was a great ego boost for me [laughs], for sure. PCC: BELAND:

PCC: BELAND: And at the end of ’78, I got a call from Greg McDonald who was an understudy of Colonel Tom Parker’s. And he had worked with Elvis and with Colonel Tom Parker. And Greg had just taken over managing Ricky. And we had a long talk. He had heard that I was a Rick Nelson fan and he also knew that I played guitar very similar to James. We both have the same style. So we were talking and he was saying, “Rick has really been beaten up in the 70s. He’s had band members that made funny faces on stage whenever he would do his old hits and stuff. And producers that were always trying to change his sound or update him and crap, when in reality, Rick Nelson should be doing what Rick Nelson is all about, which is part rock ’n’roll and part his acoustic kind of career.” He says, “We’re going to change all of that. I fired the entire band, with the exception of Tom Brumley.” They were going to keep him on for about another year. He said, “And we want to another band together behind Rick that’s the equivalent of the band that played on his early hit records — James Burton and those guys. And we want it to be just a terrific group. And we want to go back to doing a lot of his hits that he had stopped playing 20 years ago. We want to do them close to the record and the sound and the feel. And then we’re going to go into Vegas for the first time, at the Aladdin and we want it to be a memorable thing. Rick’s going to get out his old Martin guitar with the ‘Ricky’ on it. And we’re going to go back and embrace that, instead of trying to distance ourselves from it.” And Rick looked fabulous and everything like that. He was ready for it. And so Greg said, “Would you like to come on board?” And I jumped at it. And I told Dolly. Dolly’s gig was getting crazy. She was getting so big that she had a huge entourage. It was getting to be kind of ridiculous to be doing it anymore, because she was so in demand. You could hardly get close to her. So we sat down and talked. On our days off, I was hanging out with Rick and the band, rehearsing with them. So she said, “You’re really having a good time with Rick. Would you feel better playing with Rick? I would totally understand and support you, if you do.” And I told her, I said, “Yeah, I do, Dolly. Out of everything I’ve been playing, I’m really close to his music. Would you mind?” And she said no. She was so gracious about it. She said, “I’ll always love you and be here for you. But I want you to be happy and go where you feel you need to go.” So I picked up the phone and called Greg up and said, “I’m on board.” And then I went and met with Rick. And as soon as I met with Rick, I felt like I’d known him all my life. We instantly connected. We had the same sense of humor, the same love for rockabilly and early rock ’n’ roll stuff. And of course I knew all of his records, from the first one that they made all the way up to Stone Canyon Band. So that was great for him, to have somebody around him that really, really related to what he was all about. And so I became the band leader. At first I was just in the band. They were still phasing out his Stone Canyon Band career. As soon as I got with Rick, I immediately went into the studio to play on an album that Al Kooper was producing [“Back to Vienna”] on Rick. And it was at the Record Plant in Hollywood. So I wasn’t very vocal or opinionated, because I had just joined up with him. I kept pretty cool and didn’t voice my opinion on anything. So I went and did the album. And I observed what was going on around Rick and I saw first-hand what Greg was talking about. Al Kooper had all of these f-cking horrible songs he wanted Rick to record. And it was just bullshit. And he had all of these superstar players on the date — Mike McDonald, he had Rod Stewart’s drummer, all of these people coming by to play and sing. It was like “The Ed Sullivan Show” or something. And he had these songs that were so kind of weird. There was nobody on the floor really leading us or dictating what to do or having charts or arrangements. It was really just, the songs were played, and everybody played them on the floor. There were a couple in there that were pretty good, but in general… And Rick never really came out on the floor. He was in the vocal booth the whole time. I very rarely saw him. And he had very little say in anything. So it was like he wasn’t even in the studio. So I saw that all going down. And I kept thinking, “This is totally f-cked!” I mean, this is Rick Nelson. This ought to be about him… and it turned out to be like an Al Kooper album, featuring Rick Nelson. And Kooper didn’t do anything. Kooper just sat in the studio, really, and did very little. There was no production value in anything that he did, I thought. Anyway, I expressed it to Greg McDonald a couple days later. Greg said, “Well, we’re having problems on that album. Al is overspending. And the label doesn’t really like what they’ve heard.” A couple weeks later, to my surprise, I get this phone call from Greg McDonald. He asked me what I was doing on a certain date. I said, “Well, I don’t know. I’m with you guys. Whatever you’re doing, I’m doing.” He said, “Here’s what we want you to do. CBS has canned the Al Kooper album halfway through. And they fired Al Kooper. And they want Rick to slide to Memphis to do a real Ricky Nelson album [originally titled “Rockabilly Renaissance”], using producer Larry Rodgers, who produces a couple of country acts for CBS. “And we just want to fly you and Rick. And there’s a house band, a house studio unit Larry uses and they’re all great guys. So do you wanna do it?” I said, “What are the songs?” He said, “Well, we have a few that Larry’s got that are pretty good. But we want Rick and you to knock it around. See what you come up with.” I went, “Shit, yeah!” So Rick and I flew to Memphis. We had adjoining hotel suites. We stayed up late at night, playing guitar and going over songs. And we wrote a couple things. And I came up with this song “Dream Lover,” the Bobby Darin song, and I had a slow arrangement for it. And I played it for Rick and he said, “Great! Let’s do it tomorrow on the session.” And then we talked about Buddy Holly and we decided to do “Rave On.” We talked about Elvis and decided to do “That’s Alright, Mama.” We talked about the Stones and we decided to do “It’s All Over Now.” And then Larry Rodgers had a couple suggestions — “It’s Almost Saturday Night” by Fogerty and “Sleep Tight, Goodnight Man” — these really good songs. So the next day, we went to this little house in Memphis and it was just one of those old houses, like on Music Row, and they had this 16-track studio in there. And the studio was full of antiques and stuff. It was really cool and funky and old… in this really funky, black neighborhood. And there were the band members — the drummer, a bass player and guitar player, who was Bobby Neal, who later joined Rick, came on the road with us… and stayed with Rick till they died in that crash. So anyway, we instantly hit it off. We went into the studio, just off the top of our heads. I’d never seen Rick so animated. He was right there in the studio, making suggestions, laughing… and full balls-to-the-wall excitement. And we started playing some old rockabilly tunes. And it turned out Bobby Neal was a big rockabilly fanatic like me. And we cut an album that was eventually called “The Memphis Sessions.” And out of that, the single was “Dream Lover.” And that’s a song that we did on “Saturday Night Live,” after we finished the album. And it was Rick’s last chart record, that we did. It should have been a hit, but the label really blew it. The label just wasn’t that excited about Ricky. When we did “Saturday Night Live,” we were going to debut “Dream Lover” at the end of the show. And the plan was for Epic to release “Dream Lover” the next morning, to capitalize on “Saturday Night Live.” And they held the release up for almost three weeks, while someone suggested that Larry add a conga or something. They lost the momentum and the record only went up to the middle of the charts. And that was a real heartbreaker, because that was a hit record. Every time we played it live, people loved it. And when we did “The Memphis Sessions,” I became leader of the band. From that point on, Rick and I were joined at the hip, pretty much, for all the time I was with him. And when we had personnel changes, I was there to make sure that we always had a band that as good as the TV band, that really rocked and that was also supportive of Rick, too. And so every show was fun. We had the best bunch — the best road crew, best players, the nicest guys you could ever want to have around you. Extremely excellent musicians. It was the gig of gigs for me. And when I had to leave Rick to join The Flying Burrito Brothers, it tore me up. I really didn’t want to do it. But my publisher talked me into it, because it offered me the chance to be a member of The Burritos and to write for them and to produce them. It was a really big opportunity for me. And I talked to Rick about it and Rick, of course, was all supportive of it. So about six months after “Saturday Night Live” and “Dream Lover,” I left Rick to join Flying Burrito Brothers and Bobby Neal took over as the lead guitar player for Rick. The irony came, after The Burritos had broken up, after we had hit records, country hits, I was in Nashville and I got a call from Bobby Neal. He wanted to know if I wanted to come back to Rick, because he was quitting to go back home to Memphis for his wife and the kids. I jumped at the chance, because I really missed playing with Rick. I wanted to move back to California really bad, because I had had it with Nashville. So I told Bobby, “Yeah! Where are you calling from?” He said he was in some place in Arkansas or somewhere, on the way back to L.A., but they were going to stop at Rick’s buddy Pat Upton’s club in Texas to do a show before their big New Year’s Eve gig in Dallas. And right after they got back to L.A., I would take over from Bobby. Bobby said, “We’re just going to get these dates out of the way and we can make the switch. And I said, “Great!” I found a house and started to pack and everything. And then New Year’s, I got the call from my partner Gib’s son [partner Gib Guilbeau from Swampwater and The Burrito Brothers]. He said, “Have you got the TV on?” “Why?” “You better turn it on.” And I did and there were pictures of the plane on fire. And everybody dead, including Bobby and Rick and the road crew and everybody I knew. So after thinking about it, I decided to stay in Nashville for a while longer. I kind of took it as some kind of sign that maybe I should stay where I was. And I did. And I went on to work with Garth Brooks and people like that. So the plane crash kind of kept me in Nashville. And it was terrible. It was a hard thing to digest. It hit me really hard a couple of weeks after it happened. It was kind of a delayed reaction. You know, Rick was the greatest. And I don’t think there was anybody else I’ve ever worked with that came close to how much I enjoyed, how much I loved working with him. I had such a rapport with him. He was very much like me in a way. We both had the same kind of personality. And we both had the same love of our parents, our family, our mom… We had a whole lot of stuff in common which really connected us. And I felt very privileged to have been more than just a guitar player in a band with him. I was a big part of his kind of comeback that he had going on in 1979 and ’80. PCC: BELAND: His opportunity to really hit it big was that “Saturday Night Live” show. And when you know you’ve got a hit record in your pocket and you’re playing the biggest show on television to debut it, and you look fabulous and you’re all over People Magazine’s sexiest guy of the year and on the TV shows, people are screaming and fans are out there going nuts, which they did at every show — for it to not happen is a tremendous letdown. So after I left him, Rick just basically toured the world, singing the hits again, over and over. But I felt that if I’d gotten back with him, I would have, for one thing, tried to talk him out of flying in an airplane and try to get him into a bus. And then I also would have tried to work with him on his recording career. And at that time, I think I would have had a great shot at producing him. But it never happened. PCC: BELAND: But just recently Bear Family Records released the greatest box on Rick Nelson and the entire Memphis session recordings are on there, untouched and mixed by Larry Rodgers. And that’s really what you want to hear. And so, yeah, “Dream Lover” was just magic. And Rick sang it really great. And it had a real James Taylor kind of feel to it. It should have been a number one record. PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: But he has so much more of a legacy, recording-wise, than those other guys. And he had cool players playing on his records. He would have hated it, hearing the obituaries on TV, where they said, “teenage crooner, Rick Nelson,” and then they would interview somebody for a comment like Fabian or Frankie Avalon. Rick would have cringed at that. Rick was up there with Elvis and Carl Perkins and all the rest of them, the heavy hitters. PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: But I’ll tell you, his live gigs were always sold out. Chicks grabbed his clothes and jumped on the stage, screaming. The band rock-and-rolled. And, oh, man, it was the gig of my life. More than anybody else I ever worked with, that was my favorite all-time gig. PCC: BELAND: So yeah, it was a real letdown, that’s for sure. But the band we had on “Saturday Night Live” was the best band we ever had — Bobby Neal and me and Billy Thomas on drums, who later went on with Vince Gill. He’s still with him. And John Davis [bass]. Elmo Peeler on piano. And Bobby Neal, Billy Thomas and John Davis — those three guys could sing every bit as good as The Eagles. So if you listen to our live show on “Saturday Night Live,” those vocals are flawless. And like I said, everybody was just at the top of their game as players and singers. And Rick knew that. It really gave him a good kick in the ass. PCC: BELAND: Yeah, I was up there in the balcony, 19 years old, looking down. We went down for the sound check. I just stayed in the back and watched them, because it was the first thing Rick had played live in as long as anybody could remember. And it was a big deal. So I snuck in there during the day and watched Ricky Nelson get up on the stage and talk with the band and run through some tunes. And I went, “Wow! Man, this is amazing!” And then I stuck around for the show later that night and watched Rick do his show. And people went crazy. And all the people from the TV show were there — Ozzie and Harriet and Dave, his brother. So it was really a neat night. So those two shows were probably the biggest thing for Rick, the Troubadour debut and “Saturday Night Live.” because those were pure Ricky Nelson. PCC: BELAND: And he had that horrible leather case over his guitar. And it used to make his guitar sound absolutely horrible, as you can imagine, because it was a thick leather case, spelling out “Ricky Nelson” on the guitar. So at the end of the show, I went into the truck to hear the playbacks, which were fabulous. But his guitar was just god-awful. It was just bass-y. So I just actually went in and redid his acoustic guitar. But, oh, God, the show was great. And the people went absolutely nuts over him. Sold out shows for a week. I think we recorded two nights. So we did that. That was the only live album I did with Rick. We did “Dick Clark’s Live Wednesday” right before that. For that live recording, we still had Tom Brumley on steel. And the guitarists were myself and Don Preston. Billy Thomas was on drums for that one, too. It was really, really a smokin’ band. You can see a YouTube clip of the “Live Wednesday” show. I think we did “Milkcow Blues.” And we’re smokin’ and rockin’. I think you would really like it. PCC: BELAND: PCC: BELAND: And it also made me a little bit sad that Rick never made the comeback that he came so close to. So yeah, it was kind of a melancholy time. I stayed in Nashville and did really good in Nashville. But I kind of resented having to have to stay there. But I knew it was the right decision. But my heart and everything was in that airplane. And that’s what I was looking forward to in the coming months. I thought I would be in Hollywood. And I loved living in Hollywood. And I loved working with Ricky. That, to me, would have been Seventh Heaven on Earth. But there I was, stuck in Nashville for another decade. PCC: BELAND: But they were a bunch of ragtag kind of guys. They were totally undisciplined. They didn’t like to rehearse. And I felt the songs they were doing at the time really didn’t capture the spirit of what The Flying Burrito Brothers’ country-rock was really all about. They were doing more upbeat, honky tonk, barroom, Texas kind of songs. And the playing was kind of sloppy. And I didn’t necessarily get along with Skip Battin, the bass player. Even though he was in The Byrds, he was in the shitty version of The Byrds. He was a crappy songwriter. And I didn’t like that. My publisher, who I had just signed with, Bo Goldsen at Criterion Music, he had Gib signed as writer, too. So Bo suggested that on my songwriting demos — I was still with Rick at the time — the new songs I was writing, that maybe I would consider using The Flying Burrito Brothers as my session guys on the songs. So Bo had a 16-track studio below his office on Selma in Hollywood. And I had written these songs. I had a hit record going on with Zella Lehr called “Rodeo Eyes” and it was on the charts. So I started writing more and more. I brought Gib and Pete and Skip in to play on my song demos. And little did I know that the song demos were getting pitched over at Curb Records, where they loved it. But they were real commercial, mainstream country songs that I had written. I didn’t try to write for The Flying Burrito Brothers. I was trying to write for acts like The Gatlin Brothers, acts that were on the charts. Anyway, Dick Whitehouse who ran Curb Records, liked what he heard. Bo played him the tapes. And Bo came up to me and said, “Listen, if you join The Flying Burritos, I can guarantee a record deal. It would give you a chance to get your songs recorded by the group and you’d be in a hit band. And a chance for you to produce and arrange.” So I said, “Well, I’d like to be in it, but I’d definitely like to produce the band.” So I was kind of vaguely promised that that would happen for me. So I quit Rick and I joined The Burritos. And then right when I joined The Burritos, Curb said I couldn’t produce the band, that they wanted one of their staff producers to produce it. And I hit the roof and I almost quit to go back to Rick. My publisher talked me out of it. They assigned us a guy named Michael Lloyd, who was just the f-cking worst guy you could ever want to produce The Flying Burrito Brothers. He was producing people like Donny f-cking Osmond. And Leif Garrett and Shaun Cassidy. I said, “Are you guys crazy or what?” Anyway, I met with Michael Lloyd. He showed me his really expensive studio he had at his house in Beverly Hills, behind the Beverly Hills Hotel. He had all of these guys working for him. It was surreal. It was like a Hollywood fluff producer in this mansion in Beverly Hills with all this staff around him. And he played me some of the stuff he’d been recording and I mean, it sounded okay, but it wasn’t my cup of tea. I felt like I knew how The Flying Burrito Brothers should have been recorded. I mean, it was my demos that got the deal in the first place. But anyway, I was continually being told that I should play ball and not upset the boat. So we worked with Michael Lloyd. Lloyd took a real liking to me. He not only used me with The Burritos, but on a lot of the other sessions he was producing at the time. So we did this album and we ended up with three hit records. Two of them I wrote [“She’s a Friend of a Friend” and “She Belongs to Everyone But Me”] and the other one was “Does She Wish She Was Single Again.” So we had three hits. And then the label said, for the next album to not change anything and to keep Michael Lloyd, so I was like, “Oh, f-ck!” So it turned out that it was a double-edged sword. We went into the studio to do a second album and Michael produced and we had three hits off that. But I couldn’t stand to work with the guy. So milquetoast. And the records, our records, I don’t even listen to that stuff we recorded, because it sounds so… BallsLess. Other people argue with me. They say, “Oh, those are really good country records.” And they were. But The Burritos should have been cutting stuff like The Eagles, you know, stuff that had a bit more edge on it. But anyway, we toured with The Burritos, everywhere. We never got off the road during those first two albums. And we decided to move to Nashville. One of the first things, when we had gotten our record deal with The Burritos, I made it clear that I didn’t want Skip Battin involved anymore. I didn’t want to feel pressured to record his shitty songs and his shitty voice and mediocre bass guitar on our record. I’d rather hire session guys. Michael Lloyd totally agreed. So between Lloyd and I, we got Skip fired. And Michael had all session guys for the first two albums. Pete and Gib and I were the only ones on those records [though Battin’s photo appears on the cover of “Hearts on the Line.” He was fired after the photo shoot]. And it was a lot easier to record, because the session guys we used were John Hobbs [keyboards] and Dennis Belfield [bass] and Ron Krasinsky [drums] — great players. We had a real good rapport with them in the studio. And Pete played steel. And I played all the guitars and singing with Gib. And that’s how we worked that out. So by the time we got to Nashville, after our second album, we actually made the physical move there. Gib and I packed up our stuff and moved our families to Nashville, figuring, politically, it would be a good thing to do, because it would get us in with CBS/Curb in Nashville, because we were doing country. And it was a smart move on our part. And Pete was always a problem, because he had duel careers, one as a steel guitar player and the other as a highly successful film animator. And it was always before we would go on a tour that he would have to back out of a tour, because of a movie that he had to do. So we just finally agreed to have Pete just play on the songs and call it The Burrito Brothers, cut off the “Flying,” which I was totally against. I was against using The Flying Burrito Brothers name from the first day I joined the band. I wanted to call ourselves Golden West. We had hit songs. We had great credentials. And why not just start over? I felt that we were going be hammered by the press, for being The Flying Burrito Brothers, by fans of Gram Parsons in the press. And we were. That’s exactly what happened. And all the pop reviews on our albums were calling us everything but phonies, saying we were part of some fictional group Curb Records put together — all this horrible shit, when, in actuality, between Gib, Pete and I, we had more credits than Gram Parsons ever had. I mean, Gib’s songs were being recorded by Rod Stewart and The Byrds. And I had hit records. And the three of us had played on the recordings of everybody from John Lennon to The Bee Gees to Linda Ronstadt. How many more credits do you need to get any credibility? We had them, but nobody ever mentioned that. So I begged Gib and Pete and the record label and our manager and publisher to drop the name. Make an announcement that, at this time, we have agreed, the guys have decided to drop The Flying Burrito Brothers and go under the name Golden West. It would have worked perfectly. Nobody would have cared. Most of the commercial country stations at that time didn’t know who the hell Gram Parsons was anyway. But the pop critics did. So I begged and begged, but just like the production, Gib and our management wouldn’t have it. I hated walking on stage every night, being introduced as The Burrito Brothers, especially when we were a duo. And we went on to have hit records as a duo. And doing TV shows and playing at Wembley stadium — we’re walking out there, being introduced as The Burrito Brothers — I cringed every time that happened. I told Gib we should have gone out as the Gilbeau and Beland Band, something with our own names and not something that goes back 15 years before we even joined the band. But it didn’t work out that way. i was a Burrito Brother until around ’86 or ’87 and finally ended it. We had hits and I was proud of those hits. When we got to Nashville, the other guy that we fired was Michael Lloyd, the producer. We finally got him out of there. And then we were able to get Brent Maher, who was fabulous. I’d worked with Brent before. He was great. But we only had him for one song. We did a remake of “Almost Saturday Night,” the John Fogerty tune. And that was a hit. But then CBS wouldn’t hire him back, because he wanted too much. So they put us with Randy Scruggs. And I had known Randy since he was a kid, both Gib and I did. So we did a whole album with Randy, using Jerry Douglas and all these great players. Mel Tillis guested on it with us. And it had a single called “Blue and Broken-Hearted Me” and that became a hit. At the same time, we guested on an Earl Scruggs album, “Sittin’ On Top of the World.” We did two tracks with Earl. But CBS never released our album. And to this day, it’s never been heard by anybody. And it was a really good album as you can imagine, with that lineup. So Gib and I left CBS. And at that time, our manager, Martyn [Smith] died. And we ended up with Leon Russell’s company. They signed us and we went into the studio and did an album with violins and everything. And at the end of the album, Leon’s company went belly-up. So that album never came out. So that’s two back-to-back, high-dollar albums that we did that never came out. So I just said, “F-ck it. Let’s just call it a day.” And I went off with Bobby Bare, worked on the road, traveled the world with him for a couple years. And then Gib [laughs], I can’t believe he did this — he actually got together with Pete again and started another Flying Burrito Brothers band. It never got off the ground. And then Gib moved back to California. And I stayed in Nashville. PCC: BELAND: But The Bellamy Brothers asked me to play on a record of theirs called “Rollin’ Thunder” and we kind of got back together again. I played on that, with John Jorgenson. And they had a hit record from that called “She Don’t Know That She’s Perfect.” When that became a hit, they asked me to go on the road with them. And I thought this was a good opportunity for me to get back together with them and maybe get some co-writing done and maybe cash in on the fact that they were huge at that time. And I did. I went on the road with them. And I wrote two of their hits — “Cowboy Beat” and “Hard Way to Make an Easy Living.” And went out for about two-and-a-half years. And finally I had to quit, because it was just too much traveling for me. They never go home. They’re always out on the road on that bus. And at that time, I’d just had enough of it. But yeah, I ended up with an ASCAP award for “Cowboy Beat.” It was nice working with David and Howard. They’re a great act, great producers, great session musicians in the studio to work with. The whole thing was really terrific. And their whole show was nothing but number one country hits. That was pretty cool. And then I got The Flying Burrito Brothers back together again and we did an album that I produced, called “California Jukebox.” And it was a great album. I think it was the best thing we ever did. And I put that together and I got Merle Haggard to sing with us and Waylon Jennings. It was really great tunes and stuff. And then right in the middle of the next album, “Sons of the Golden West,” Pete had to back out. And then Gib got sick. He had a heart attack. And I found myself being in the middle of an album, being the only Flying Burrito Brother. So I got Larry Patton, a friend of mine, a great singer, to come in and sing and we used session musicians. And we did a great album. And then that was the last of The Burritos that I did. That was right up to 2000. And then I moved back to California that year, too. I got into producing and going over to Europe quite a bit to produce records. I started to get calls to produce records in Norway and Germany and a lot of work in Australia. And that’s kind of what I’m still doing, besides “Best Seat in the House” stuff. I still play on people’s sessions, too. I have my own studio on the ranch here in Texas. Last year, I did some guitar parts of an album that was being recorded in Paris. I was flying in the guitar solos and stuff [laughs]. And sometimes I fly to where the act is at and I’ll produce them there. I’ve been to Colorado and Wisconsin and Baltimore. I come in and work with bands and acts. But now I’m focusing my attention on “Best Seat in the House.” Hopefully there’ll be a volume two and, if that’s the case, I’ll do another CD for it and continue and do the show. The live shows are great, because I love talking to audiences and telling them the stories. And it goes over fabulous. I think people really want to hear what it was like in those days. I take them back to working with Linda and Arlo and a lot of the songs I worked on that became standards that they grew up with. And I have so much fun when I do it. Then I play some of the songs that I did. PCC: BELAND: And now when I go back and glance at the book, see the pictures, I just feel really kind of blessed that I had the opportunity to do all that stuff and to have people in my life who came and went, who took me under their wings, when they didn’t have to, and showed me the ropes and kind of guided me along the way. So it’s kind of like being Forrest Gump. I was there in all of these historical times. And I think that’s the proudest I am. And I’m also proud that I have three kids who are also in the business. My son Tyler is a beat producer, engineer and accomplished guitarist in Napa, California. Extremely talented in the studio. As I mentioned, Chris is an established singer-songwriter in Northern California with a number of beautiful CDs to his credit. He's amazing. And my granddaughter Gabby is a soulful singer who is unbelievable. She's in New Orleans, knocking folks out. And I made my parents proud. When I first started doing this, they were scared shitless. They didn’t know what was going to happen to me. And it all turned out good, in spite of dropping out of high school and having my music teachers fail me and kind of make fun of my interest in pop music, in spite of all that negativity that I received when I was in high school. At that time, back in ’65, ’66, the high schools were anything but encouraging. The music teachers were always laughing at you, if you had any visions of being a professional. And it was a stroke of luck. Just like a miracle. All of a sudden, my dad announces that I’m going to be leaving my little town, we’re moving to California. And I gotta tell you, when I was playing guitars as a little kid, we had these railroad tracks that used to run through my town, Hometown, and I used to look down the tracks thinking, “If you follow these tracks, they’d take you right to Hollywood where Ricky Nelson and those guys were making records.” I used to think about. And I’ll be damned if one day my dad didn’t just say, “We’re going to California.” Had it not been for him, I don’t know if I would have made it out there. So yeah, it all worked. And when I look at it through the book, I’m quite overwhelmed at times myself. I wish there was time to do even more. Especially after finishing the book, it seems like these memories all happened a week ago. And I’m still standing. For the latest news on this artist, visit www.facebook.com/johnedwardbeland or www.johnbeland.com. |