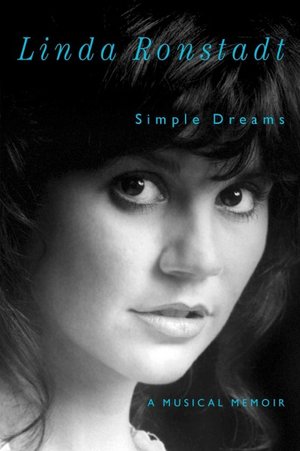

LINDA RONSTADT: A VOICE FOR THE AGES

Linda Ronstadt - one of the greatest singers of her generation... or any generation. Her first hit, Michael Nesmith’s “Different Drum,” recorded in 1966 with The Stone Poneys band, made listeners fall in love with that extraordinary voice. After that, it was one gorgeous vocal after another. Ronstadt’s ability to move and electrify audiences grew year after year. She amassed an incredible number of chart records and prestigious awards. She released more than 30 studio albums. Classic Ronstadt singles include “Will You Me Tomorrow,” “Long, Long Time,” “Love Has No Pride,” “Silver Threads and Golden Needles,” “You’re No Good,” “When Will I Be Loved,” “Tracks of My Tears,” “Blue Bayou,” “It’s So Easy” and “Ooh Baby Baby.” Her passion for music took her from rock ‘n’ roll and country to operetta, traditional Mexican music and the Great American Songbook. Ronstadt breathed new life into every genre she explored. Ronstadt tells her own story in the new book, “Simple Dreams: A Musical Memoir.” In December of 2012, she revealed that Parkinson’s Disease had robbed her of the ability to sing. But her decades of glorious, heartfelt recordings continue to enthrall us. We interviewed Ronstadt in 1996, following the release of her album, “Feels Like Home.” For fans, her body of work will always feel like home. POP CULTURE CLASSICS: Do you feel like you’re making a return to Americana roots? LINDA RONSTADT: I really don’t. People keep saying “return.” I’m going, “Wait a minute. ‘After The Gold Rush,’ ‘Blue Train’? Return to what?” Except for what I started on the last record, which was a real determined effort to sort of experiment with glass instruments. I’d begun working with them, with this thing of building up layers. I call it sound laminating. I do layers and layers of vocals, combinations of voice and glass, voice and the orchestra, and do more of a kind of vocal ambiance. People hear it and sometimes think it’s synthesizers. And sometimes it is. And a lot of times, it’s just me doing five tracks of one vocal harmony after another, just to kind of be making sound curtains in the background. But I think those are real different-sounding records for me. I think they’re innovative in the industry. I’m very happy about them. And I’d like to continue doing that. In terms of the fact that there was some sort of Country bias to this record, the reason for that is because it started out to be a record with the Trio. And we had done a lot of, not contemporary country music, but traditional, pre-bluegrass material, which is where we have a common musical sensibility, Dolly, Emmylou and I. So when that became an impossible thing to bring out to the public, and I was left with these tracks, that I’d done a great deal of work on, there was some frustration about them possibly not seeing the light of day. I wanted to use them. So I had to incorporate them into a record of my own. So I chose the mandolin to be the common thread, so to speak, and used it to kind of graft on this traditional stuff to more contemporary stuff like “The Waiting” and “Walk On.” PCC: Is there any particular musical style that feels more like a home to you? RONSTADT: Well, Mexican music is where I’m very happy and feel is the most authentic expression of my own personal and musical self. PCC: Is that because of the emotional content? RONSTADT: That’s what I grew up singing first. And all the stuff that I’ve experimented with has been going farther and farther back into my own personal musical background that I had with my family. The first music I ever heard was always in Spanish. I never heard anyone singing in English unless I turned the radio on. My Mom would sing in English a little bit. But mostly it was my father singing in Spanish. To me, Spanish was what you sang. English was what you spoke. Then I heard some country music, because we were in Tucson, we heard “The Grand Ole Opry.” And there’s a lot of country music in Arizona, of course. And then I heard rock ‘n’ roll. I heard a lot of choral music, because my brother was a boy soprano. I heard a lot of opera, because my grandmother is an opera fan. And there were a lot of people in my family that played the piano and sang. They sang in Italian or Spanish or French or whatever they needed to sing in, because they all loved opera. And then my sister was in a Gilbert & Sullivan operetta. And Mom always loved Gilbert & Sullivan. So we heard a lot of that, when I was growing up. So rock ‘n’ roll was really what I came to last. And it was something I was the least secure in. And it was the thing, frankly, I found the least satisfaction in, as a vocalist. PCC: Is that still in the past tense. Has that changed over the years? RONSTADT: Well, now that I’ve had a chance to go back to those other areas, where I was a little bit more sure of my footing, and was able to refine my abilities as a singer, which I really didn’t get much of a chance to with American contemporary pop music. It’s really not written for vocalists. Then I’ve had a chance to come back and pick and choose contemporary pop material in a way where I have something to do [laughs]. You know, like the last record, I really focused on the great vocal, kind of walls of sound style records that were made, songs that were written by Burt Bacharach for Dionne Warwick or Dusty Springfield. They were great vocalists, those women. And those songs are particularly constructed for those voices. And I can do that. I have that real wide range. So I can sing over that range of music, whatever it is. It’s like a very wide kind of music, musically and dynamically. So I’ve learned to do that. That’s kind of my stock in trade, coming out of Mexican music. After trying to sing a huapongo, I mean, a song that’s written in 4/4, with the accent on two and four, is like falling off a log. It’s easy. PCC: Delving into different genres, in addition to gaining self-assurance, can you take elements of technique you’ve learned from one to another RONSTADT: Oh, yes. The technique is very applicable. It always was. My technique always was based on Lola Beltran, who’s a belter. But the reason I had trouble with rock ‘n’ roll, initially, was because I’d based myself so much on what I’d heard from Lola Beltran, who was a belter, but didn’t come from a tradition of black music. Rock ‘n’ roll is based on American black music. Lola Beltran sang rancheras, which is based on pre-Columbian traditions, really. It has indigenous Mexican rhythms, but is not like other kind of Mexican music, which is tropical music, which is based on African music. And so, when I sang the rancheras, I learned so much about rhythm. And then, when I went to tropical music, I did an album of tropical music, which is all West African-based, which I did after I’d worked with Aaron Neville and I really studied West African influence in the new world and Creole music. I really started to understand how that stuff is phrased. So there’s a lot of that stuff that’s still buried in rock ‘n’ roll. It’s hard to find it. Mostly it’s in the rock n’ roll that comes out of New Orleans. When there’s a five-beat influence now, I just eat that for lunch. It’s easy for me. Of course, all of the American jazz standards are based on the five-beat rhythm. PCC: Having tried light opera and classic pop, among other genres, can you find enough challenges in rock or folk?

Yeah, there’s some good stuff. Especially if I can put enough of a traditional spin on it. Songs like “High Sierra,” or even “Blue Train,” which was a song that written here in the United States, but Emmy found that from an Irish singer, so it has this amazing feel of Irish vocalizing added to it, which is real accessible to Emmy and me, because we’re big Irish music fans. Those songs are joy to sing. PCC: Do you find any sort of connective thread among all the different types of music you’ve sung? RONSTADT: Mostly just that they’re traditional. Most of the stuff I do has a strong traditional bias. The Mexican stuff I sing is all traditional Mexican folk music, except for the tropical stuff, which is more urban. It’s equivalent to the Nelson Riddle stuff. It’s the same route and the same style basically, different language. And all the country stuff that I’ve sung has been mostly bluegrass or old-timey stuff. I haven’t sung much contemporary country music, because it just doesn’t interest me very much. PCC: What about the evolution that rock has gone through, since the days when country-rock hit the Top 40? RONSTADT: Well, even in those days, even when I was doing pop music in the 60s and 70s, I was still exploring pop music with a strong, traditional foundation to it. PCC: Do you find that there’s a resurgence of interest in a more rootsy type of music? RONSTADT: No, I don’t, actually. Actually, I think we’re losing what was agrarian music, because we don’t have an agrarian lifestyle particularly anymore. It’s all corporate. There’s these big corporations that own these big factory farms. The idea of the family farm is ceasing to exist. Having grown up in a rural atmosphere, I grew in the West, 15 acres of my grandfather’s cattle ranch, and my family had been ranchers for generations. So I was drawn to that kind of music. But it’s disappearing from our life in North America. There’s still a little bit of it left in Mexico. So I headed south as fast as I could, because you can still find real authenticity down there. But that’s disappearing. PCC: What about the corporate nature of the music industry? You seemed to have escaped its grasp to a large extent. RONSTADT: It’s never hampered me, particularly. I mean, I would have sung Mexican music sooner, if I hadn’t had to sort of have their permission, so to speak. But, as it was, I waited until I had enough clout until I could do it without their permission. And they had to take what I gave them... and they were happy to have it. So I waited until I had earned enough clout myself. But see, with music, the recording industry’s never been quite the same as it is with movies. It’s not as much of an initial expenditure that you have to risk. So automatically, it’s not so much art by committee. And since I’m not a person who would ever be happy working that way, there wouldn’t have been a choice. I wouldn’t have done it. If I would have had some suit breathing down my neck, I’d have just told him to go shove it. I would have gone to work slinging hamburgers or whatever else I could do. And I would continue to sing, just for the love of the music. PCC: You need that control, because you’re strong-minded? Or a perfectionist? RONSTADT: It’s just that I’m interested in expressing my own musical opinion, not somebody else’s. You know, it happens in the music business right now, it does happen, the president of such-and-such records will send out his A&R guy that comes into studio and says, “Well, we think you ought to do this. We think you ought to do that.” Well, okay, that can happen to other artists. It’s not going to happen to me. I was signed to labels at the time when they weren’t very interested in interfering with artists’ development in that way. And by the time it changed, I had enough status at the label that I didn’t have to put up with that kind of treatment. And I feel that I can continue to do that. I feel I have a couple more records I’ll probably want to make. I’m nearly 50. I won’t want to be recording forever. And I certainly don’t want to be touring forever. But the music will always be there. I’m happy if I sing with my brother or my cousins or if I sing with a little boys choir or whatever’s around, I always investigate. Like up in San Francisco, I found a men and boys choir at the Grace Episcopal church there. They’re absolutely wonderful. And I worked with them on Aaron Neville’s record. I used them on several tracks, when I produced Aaron’s record. And I found David Grisman, who’s a brilliant, brilliant musician. And I thoroughly enjoyed working with him. It was absolutely a pleasure and a privilege, I felt, to work with a musician of that capability. And I’m just as happy sitting down and singing with Herbie Pedersen and Carl Jackson, as I am singing with, I don’t know, Smokey Robinson or whoever else. I’ll always find music wherever I go. I found a good player in Tucson. And, if I end up living in Tucson and singing with the choir, I’d be just as happy to do that. It doesn’t really matter to me, because I love the music. And I don’t have to make a living at it, particularly anymore, if I don’t want to. I suppose I could retire and figure some sensible way to save my money and live off of what I’ve earned. If I’m careful, I probably could stretch it out for most of my life. But, you know, I couldn’t live the lifestyle that I’ve lived. But I could do it, if wanted to. And that gives me a certain amount of confidence. PCC: What are some of the accoutrements of the lifestyle you wouldn’t mind giving up? RONSTADT: Well, I don’t know. I’m sure being able to buy whatever you see in the grocery store or the market or the drug store or whatever. I mean, I live a pretty simple life anyway. But it’s just the feeling that you don’t have to worry, if you spend $100 at the market or if you know you should only spend $25 at the market. That’s a big difference. And I remember the days when I had to worry about that. PCC: In terms of age being a factor in the career, it doesn’t seem to be much as much of a factor outside of rock ‘n’ roll. Jazz and blues artists go on forever. RONSTADT: I don’t think it’s a factor anywhere. I think what it is, is whether you have a story to present and whether you’re able to present it clearly. And whether you’re presenting something that’s truly authentic to yourself at that point. I mean, I don’t sing the songs that I would have sung as a 19-year-old or as a 25-year-old or as a 35-year-old. They’re not necessarily appropriate for me. The kind of songs that I’ve simply dropped from my repertoire, because I’m not interested in singing them. They’re don’t express what I need to express right now. But there are plenty of songs that will always be appropriate no matter what, a song like “A Ghost Of A Chance” or a song like “Someone To Watch Over Me” or a song like “Women ‘Cross The River” or a song like “High Sierra,” those songs don’t come from any particular age bracket. A song like, “It’s So Easy To Fall In Love,” I sang as a young person. It had a little sassy thing to it, a little flippant thing to it. It’s a nice song. It’s nicely constructed. I’m a huge Buddy Holly fan. But it’s not a song I particularly need to sing right now. Whereas, a song like “Anyone Who Had A Heart,” I feel like I’d be able to sing that, when I’m 80, if I wanted to. I saw these Gypsy singers singing in this flamenco show one time and these women got up and there were these old women, they were in their 50s or their 60s and they were dumpy and they had no figures and no faces to speak of. And they got up and they did this dance and they were absolutely riveting, stunning examples of female yearning and experience. And then they opened their mouths and they started to sing and they sang with their whole lives. And you heard about their childhood experiences, their first crush, their first love, the babies they had, the men who betrayed them, the men they betrayed. The whole story is in there. And Mexican music is that way. It’s like, I met this challenge to my life and I triumphed over it and I’m still a humane, whole, healthy human being and we have another day to live, so let’s celebrate. Because life is not so trivial down there in Mexico as it often has been here. They’ve gone through all these revolutions and all this horrible economic terror and a lot of bullying by the United States. And they celebrate every new day. It’s a great thing to be able to live. We take it a little more for granted, although I don’t think we’re quite going to have that luxury in the next 15, 20 years. PCC: Can you kind of trace your own life through the recordings, back from the beginning, seeing how it’s evolved?

Yeah, it has evolved so that I came more and more into an authentic expression of who I am and what I am. It was probably the farthest away, when I first started recording. And it’s the closest now. And it’s mainly because I was able to go back to my childhood and explore the kinds of music that I did, firmly put in place, when I was two and three years old, my first musical experiences. And they’re still my most authentic musical expressions. And I was able to bring that up to a professional level on a recording and go out and perform it in public and develop it and refine it. And that gave me a little bit sharper tools for pop music. Because pop music had just bored me silly. I was bored with it. I was frustrated with it. I wasn’t challenged by it. I felt that it was shallow. I wasn’t singing songs that I felt gave me anything to sink my teeth into. Whereas people like Emmylou Harris or even Jennifer Warnes, who were my contemporaries, were. And I loved what they were doing. I envied them what they were doing. I wanted to emulate that. I wanted to find ways to bring what I had done. Everything I had sung as a child was a more worthy song, I thought, than most of the material I was singing onstage in the 70s. You know, those are beautiful songs world-class songs, all the Mexican stuff, the Mexican traditional stuff and also the Mexican jazz standards that I delved into on the tropical record I made. Those are world-class songs, beautiful pieces of material, very sophisticated. And they were much better for a singer. And they had much more of an expression of what my life was about, even though somebody else wrote the lyrics. And more of an expression of what human endeavor was. PCC: But even if you were bored by some of the pop hits, it seemed, from the outside, that it was a tremendous gamble to try all these other things. Did it seem that way to you? RONSTADT: No, because I wasn’t risking anything. I was risking nothing. I didn’t get into music to make money and to be famous. I got into music, so I could play music. And so I had nothing to lose, but a bunch of stuff that was boring me and frustrating me. I got free of it. I mean, I felt like I had gotten out of a box and spread my wings and flown away from this completely boring, bleak horizon. PCC: What about Broadway? The critics could have been skeptical and vicious at the idea of a rock singer coming in and singing operetta in “Pirates of Penzance.” RONSTADT: I don’t give a pin about reviews. But we got excellent reviews about “Pirates.” And I don’t care. That wasn’t why I did it. I didn’t do it for praise. I did it, because I wanted to do it. I loved the music. And I wanted the experience. PCC: Is it important to you to surprise yourself? RONSTADT: No, it’s important to me to go back and do more familiar things. I don’t like surprises [laughs]. I really don’t. I don’t like surprises and I don’t like doing new things. I like doing things that I’m more and more familiar with. PCC: I understand there’s some talk about a choral album? RONSTADT: Well, my brother was a very, very fine boy soprano. So I heard a lot of choral music, growing up, because he performed with a world-class boys choir. And I’d love to do more choral music. It just depends on whether I can get studio time this summer and where it is and what choir is available to me. But the way I can experiment with choral music and brass music is if I do a Christmas record, because that’s music that the record company can package and sell. Otherwise, I have to do it privately. If I’m going to sell it, then it has to be something that’s accessible to enough people to make my expenses back. PCC: I imagine it would be a lot of material we wouldn’t necessarily expect from a Christmas album. RONSTADT: No, you know, there’s a lot of 18th century Christmas music that’s just beautiful. Or there’s a beautiful Spanish carol and a beautiful French carol I’d love to sing. There’s a German version of “Away In A Manger” that’s just beautiful. And there’s some nice 19th century stuff that we might associate more with a Salvation Army Band. And then there’s a song that Joni Mitchell wrote, “River,” that isn’t a Christmas song, but has mention of Christmas season in it. I just figure there's a lot of stuff that I could do and get away with, if I wanted to say, “Okay, this is a Christmas record,” you know [laughs]. PCC: What about producing? Would you like to do more of that? RONSTADT: I like producing .I really enjoy it. But I’ve been producing my own stuff. Producing other people’s stuff, I did a record for Jimmy Webb and I did a record for Aaron Neville and I did a record for David Lindley and I did a record for Mariachi Los Camperos. And I produced, with George Massenburg, the Trio record, which was completely finished before I had to take it apart and restructure it to make my own record. So George and I produced two records together last year. And it took a huge amount of our time. It took us six months to wade through those particular projects, because they had so many strange twists and turns and frustrations. So it takes up all of my time. If I do one of my own records and go out to promote it, and have some time off, which I need to spend with my family, then that pretty much takes up more than the year [laughs]. So it becomes real hard. I was asked to do a record for New Orleans singer that I admire very much, by the record company this year. And I’m trying to think of when I could do it. It’s going to take me all summer to do my Christmas record. And then I’ll have to put it out in the fall and then I’ll have to promote it a little bit. So I wouldn’t be able to even think of going into the studio with somebody else until after next New Year’s. PCC: Producing other artists, is that as gratifying in its own way, as performing is for you? RONSTADT: I don’t like to perform, so it’s fine with me that I get to stay off the road and in the studio. I love the studio. But it’s just a joy, to work with an artist that you admire, trying to make things sound the best they possibly can. And bringing that to fruition, someone’s art that you already admire, and watching it mature and develop into its full flower, it’s just a pleasure. And by producing Jimmy’s record, I learned, I really refined my own knowledge of how to sing his music. I really admire him as a writer. He’s one of the really great pop writers of our time. Because I think most of the really great pop writers are from the first 50 years of the 20th century, not the second 50 years. But Jimmy is one of the ones from the second 50 years that is really a great pop composer. A real songwriter, as opposed to being a slash-guitar player or whatever. I mean, all those people are very worthy, the Keith Richards and the Eric Claptons of the world. They’ve added a great deal to the musical literature. But not in terms of being songwriters. They’ve added a great of style and interesting musical stuff and interesting recording. But in terms of being a great songwriter, there’s Randy Newman, there’s Jimmy Webb, there’s Paul Simon, and not many other ones. There are a few other really good songwriters. Burt Bacharach is really good. I can’t think of many. PCC: Why do you think there are so few women producers?

I don’t know. I never gave it a thought [laughs]. I never had any trouble with it. I always co-produced my records. And then eventually, Peter [Asher] went on to become vice-president of a record company and a lot of stuff. And George and I worked together so long, we just kept on making records. And other people liked working with us. When Aaron came to work on my record, he loved the way George and I worked and he asked if we’d produce a record for him. We have evolved a certain way of doing vocal overdubs and layering records up. We’ve also done things live. The “Comparos” record was completely live and it was really exciting to do it that way. We could work in a number of different formats. But we just love to work together. PCC: You said you hate performing. Do you mean just the traveling? RONSTADT: I don’t like going on the road. It’s just too physically brutalizing, just to start with. And it’s too reality-shattering. You’re cruising along at home. You have a little routine. In the morning, you eat bagels and read your mail. You live in a certain place and get to sleep in the same bed every night. And you don’t have to throw your body around the planet and your body gets there 15 days before the rest of you does. It’s just an awful life. I don’t like it. And it just shatters reality. You’re leading an episodic life. There’s no continuity. You can’t build on friendships. You can’t build on relationships. You can’t build on perfecting your own sanity or refining it or anything. And physically, it’s too hard. You catch every germ that’s on the plane. There’s never time to exercise. And you can’t eat right. It’s an inhuman way to live. I don’t like it. I never liked it. PCC: You’ve managed to avoid talking much about your personal life over the years. Has that been difficult to accomplish? RONSTADT: Oh, I’ve avoided talking about my personal life very successfully. People write whatever they want, guessing or just making it up out of whole cloth. PCC: Is there an advantage to keeping an air of mystery? RONSTADT: No, it’s just whatever people want to do. I talk about the music. That’s what is your business. And that’s what I’m interested in talking about... in the public forum. But people will write whatever they want. Jackie Onassis, from the time that her husband was murdered to the day she died, she did only one interview. And that was about literary things and about the fact that she was an editor at a publishing house. It had absolutely nothing to do with her personal life at all, just about her work. She never gave any interviews, yet there was stuff that manufactured about her daily. She had a whole paper and print version of herself that marched around the globe, acting out a shadow, parallel existence of her life. She had absolutely no control over it. So it didn’t have to concern her. And that’s the way I feel. I don’t have to think about it. PCC: Do you feel that you reveal yourself through your music, that people know you that way? RONSTADT: Not necessarily. I mean, music’s very personal to me. But I don’t think somebody listening to it, who didn’t know me or even someone that did know me, would necessarily know what I was singing about, what personal thing. When I was singing “Blue Train,” which has lovely, haunting lyrics, what was really in my brain was, I’d been watching Brian Boitano skate. And that was in my brain. PCC: You’re living in San Francisco. You’ve got kids. Do you consider yourself pretty well settled now? RONSTADT: Well, I’ve always been settled in the music [laughs]. I go make a record every year. I perform. But even if I wasn’t doing it professionally, I’d be singing. I’d probably go join the Oakland Interfaith Gospel Choir and sing with them. There’s always stuff to do, musically, that’s just as exciting to me as singing at Carnegie Hall... more so, in fact, because there’s less pressure [laughs]. I’ve always sung and I always will. |