|

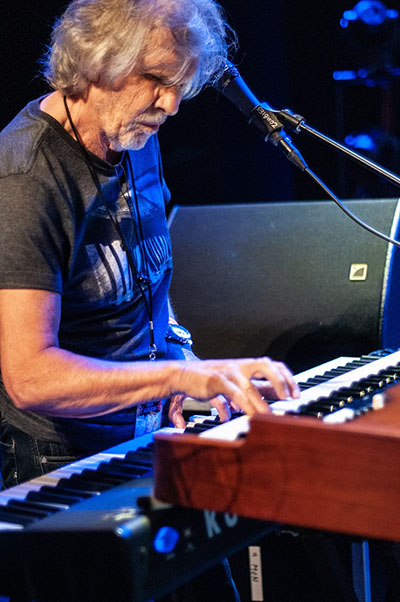

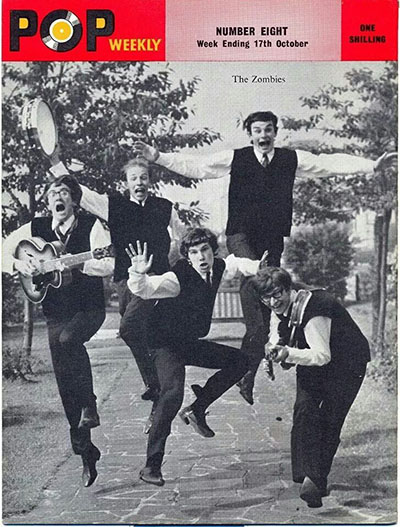

ROD ARGENT: THIS ZOMBIE'S MUSIC WILL LIVE FOREVER PCC's Interview with the Legendary Keyboardist & Songwriter -- Founding Member of The Zombies and Argent

By Paul Freeman [September 2018 Interview] He has written breathtakingly beautiful music, as well as songs that rock you right down to your toes. And his keyboard work is jaw-dropping in its wizardry. Rod Argent has carved out a prominent place in rock history. He formed The Zombies in 1961. Argent was but 15 at the time. The band, innovative in its genre-blending, began recording in 1964. Two striking Argent numbers became haunting hits -- "She's Not There" and "Tell Her No." But the UK radio ignore the band after that and worthwhile gigs became hard to come by. They mustered all their creative powers and birthed their masterpiece album, "Odessey and Oracle" (the misspelling of "Odessey" in the title resulted from the LP cover designer's typo]. This intricate, sophisticated and diverse work, recorded in 1967, was ahead of its time. It went nowhere. But after one American disc jockey discovered the single "Time of the Season," that song slowly mushroomed into a massive 1969 hit on this side of the Atlantic. The Zombies, however, had already broken up. Argent had formed a new band, appropriately called "Argent." They thrived from 1969 to 1976 and recorded such memorable tunes as "Hold Your Head Up," which features what Rick Wakeman has called the greatest organ solo he's ever heard. That single reached number five in the U.S. and sold over a million copies. They enjoyed another hit with "God Gave Rock and Roll to You." In the 80s, Rod Argent wrote music for television programs and played a number of notable sessions, including The Who's "Who Are You." He then formed a production company with former Van Morrison drummer Peter Van Hooke and produced such artists as Tanita Tikaram, Nanci Griffith and Jules Shear. Argent re-teamed with Zombies vocalist Colin Blunstone for several 1999 shows. That blossomed into a full-fledged Zombies revival. Through tireless touring and dazzling live performances, the new version of the band has built a fervent and ever larger, international following. Crowds go wild over the astonishing harmonies and sweeping instrumentation. In 2017, the original surviving band members -- Argent, Blunstone, Chris White (bass) and Hugh Grundy (drums) -- reunited to tour North America, playing "Odessey and Oracle" in its entirety. Rolling Stone listed it at number 100 among the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. Such artists as Robert Plant and Dave Grohl have cited it as an influence. Since returning from the dead, the 21st century Zombies have recorded several fabulous new albums, the latest being 2015's "Still Got That Hunger." It garnered rave reviews. The band's music remains awe-inspiring. We spoke with Rod Argent just after he arrived in Los Angeles to prepare for The Zombies' upcoming 2018 summer tour. POP CULTURE CLASSICS: ROD ARGENT: PCC: ARGENT: PCC: ARGENT: When my voice started changing, I guess I was about 14 or 15, the master of music there persuaded me to stay on the men's side. Well, it was only going to be a year. He kept saying, "Oh, can you stay a bit longer?" But I had already started forming the band [laughs]. So it became a bit difficult. But I would say that was a wonderful sort of indirect musical education. And it gave me a really natural sense of harmony and made me feel very at home, as far as all that was concerned, I'd have to say. PCC:

ARGENT: So there was a piano in the house and I discovered that I had this sort of natural sense of where the notes were in the scale. And even when I was really young, if someone gave me an instrument like a harmonica, perhaps, I could instantly play it. Even when I was seven, eight years old, I could get a tune out of it. I could sort of visualize the whole notes and the half notes in the scale somehow. It's a natural thing to me. So I was always aware of that. I was always passionate about music. But I hadn't heard any pop music that I really liked. At the time, it was a pretty anodyne, if you like, music scene, in the early 50s... before Elvis came on the scene. And then, suddenly, I was played Elvis, singing "Hound Dog." That's what really turned my world around. And I started from that point onwards, desperately wanting to be in a band. And as far as the piano was concerned, I loved sports at that age. I loved football -- or what you call "soccer" over here. But instead of playing with my friends out front, where we had a big grass verge, in the estate I was on -- It was just a council estate. It was very working class -- But I would instead, even during the long summer holidays, I would stay in and get immersed in working out harmonies and what chords went with what notes. And I started to work out how to play some of the songs that were around at the time, from the radio. And I was absolutely fascinated. And really, I was largely self-taught, to be honest. I had two years of piano lessons, from the age of about nine to 11. But I think I played less during those two years than at any time before or since. It sort of took away the adventure in a way and made it much more pedestrian. But I always was absolutely fascinated by the piano, by music and by harmonies. And that was where I started, I guess. And then when I started to become really smitten with the early, raw rock 'n' roll of Elvis, Little Richard, Buddy Holly, people like that. I really started to try and work out everything that they were doing. I never copied solos. I never copied them note for note, I have to say. But I always listened avidly to them. And that's where that real passion and interest started, from the age of 11 onwards, I would say. PCC: ARGENT: I mean, obviously Paul McCartney and John Lennon and all the people that were starting to be in fledgling groups at that time were having the same experience, I guess. And that, in an indirect way, that rhythm & blues thing, did really subconsciously affect my songwriting. But also the fact that even while I was discovering those early rock 'n' roll records, and loving them -- and I still do love those really early ones, from '55, '56, '57 -- even at that time I was still passionate about what I was hearing in jazz, for instance. It was a really fantastic time for jazz. And at that time, there was a 1958 Miles Davis group that included John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley... and then about 1960, Bill Evans joined, the pianist. I still play him quite a lot, actually. That was a magical time for most sorts of music. There was a real explosion of exploration and honesty going on. People were just so enthusiastic about what they were discovering about how to play. And about the music and the things they were being introduced to around them. And I was very, very lucky to be at that age at that time. It's very interesting, having just mentioned the Miles Davis band -- when Pat Metheny was just starting out, I was taken along to a very small concert that he did in his early days in New York. And I was introduced to Pat Metheny. I was over there with some other musicians -- Gary Moore, Jon Hiseman -- basically to play an Andrew Lloyd Webber piece, which had become a number one record in the UK called "Variations" and I played the keyboards on that. And Andrew was trying to mount a couple of performances over there. So we were over there. Jon Hiseman and Barbara Thompson, his wife, were very, very heavily into jazz. That's where they came from. And they tended to know jazz musicians over there. And we went along. So I was introduced to Pat Metheny backstage. And Jeff Berlin, the jazz bass player, who didn't know who I was -- no reason why he should, really -- he said, "Oh, Pat, this is Rod Argent." And Pat Metheny said, "Oh, man! You wrote 'She's Not There.' That was the record that made me feel I had a way ahead in what I wanted to do." He said, "All that modal influence you put into it..." And I thought, "I didn't put any modal influence into it. There was no modal influence." And then, I went home and started playing it and what I'd always thought of as just two fairly ordinary chord changes, I'd actually fashioned a little modal sequence over it to tie those two chords together. And that without ever thinking about it. And it was totally subconscious. I never thought in any way of introducing any jazz into what we were doing. I just thought we were playing rock 'n' roll. That was an example of hearing those early, eclectic styles of music and then having it indirectly influence. So I think hearing such a wide variety of music was a big influence on my writing. But then also, apart from that, keyboard-wise, Bill Evans blew me away, when I first heard him with the Miles Davis band. The first time I heard Jimmy Smith, on what were, for me, his early records, like "Walk on the Wild Side," for instance, I was just blown away with that. I just thought that was fantastic. And it made me want to capture some of that spirit in playing. So that was an influence. But as I said, I never went and dissected those records. I've never done that. I've never worked out note-for-note how the solos were constructed. It was just an overall thing that hit my ears and I just introduced my own feeling into things. But certainly Jimmy Smith and Bill Evans, from a jazz point of view, even though I loved rock 'n' roll. And of course, when The Beatles came out, a couple of years earlier than we did -- it was '62 really, when they made such an explosive impact in the UK, I guess it was '64 in the States. -- they were an enormous influence. But I think they were an enormous influence on everybody, including the Stones. I mean, I think the Stones, from the beginning, were hugely influenced by The Beatles. The Beatles were bringing out a sort pick guitar thing on "I Feel Fine," something like that. And the next thing by the Stones would have a pick guitar thing at the beginning [laughs]. They did have their specific purist blues influences, the Stones. But they also were incredibly affected and influenced by everything else that was going on and particularly The Beatles, I think. So The Beatles were a huge influence. But I would say, keyboard-wise, I can't think of anyone really, apart from Bill Evans and Jimmy Smith in those early days. And honestly, I wasn't playing jazz. But maybe that's how some of those improvised episodes on the stuff that I was doing came into being part of our music. And I would say that they're the two keyboard players that I can think of immediately. PCC:

ARGENT: So it's a bit of a magical process, in a sense. And I do think that it's a way of tapping into the subconscious, into the unconscious and into something that everyone, or most people, can relate to and recognize and can, in some way, get moved emotionally by. So it's all a very strange thing. So being influenced by the subconscious, I do think that's an important part of it. Having said that, I don't think you can ever learn too much about what people have learned to make a great effect, etc., etc. So I don't think you can have too much technique. But it should just be there not to be used consciously. It should be used as the building blocks which come to you naturally. But in a way, that immediate visualization of something... For about 12 years, after Argent came off the road, I did almost nothing but write music for TV films and TV themes, etc., including football -- as you would say, "soccer" -- World Cup. A couple of those for television. And the way I used to do those, I would just take a piece of manuscript paper, wander around the garden, and literally in about 10 minutes, somehow, something would come out of the air to me, a tune. I would then work on the chords and harmonies, etc. But the actual structure and the melody of the piece would often be done in about five or 10 minutes for those things. I mean, that's not the case with songs for me. And in the end, you're not quite sure where they come from. It's just something for which you imagine a sort of atmosphere and something going on and you sing a melody to yourself and you write it down and there, you've got it. It's all a bit inexplicable. So I do think that letting the subconscious have its way can be a big part of it, yeah. PCC: ARGENT: And I was supposed to go back into the finals. They had a big finals week and you got a free week's holiday there for these big finals. But because of my school commitments, I couldn't go back to do it. But that was the early experience. But yeah, I embraced it right from the beginning really. PCC: ARGENT: Music was the world to me. I always remember John Lennon's quote, saying that, to him, when he was young, music was the real world and what people think of as the real world was a sort of peripheral, to him. It was sort of vaguely going on outside. And I did feel like that. Music felt, to me, what was a natural way of communicating and it's really where I felt at home. And that felt like reality. I think that everything is much more vivid and stronger when you're in your discovery period really, in your teenage years, particularly. If you've got a flair or a real enthusiasm, I think that's when you become most affected by things. So certainly around that time, that really felt like that to me. And I often talk with Colin about it and it was only a few years ago that he turned to me and said, "I think I've got to accept now that I'm in this for good" [laughs]. But all the while along, he would say, "Oh, if I can come out of this with some small amount of money," he'd say. And I'd say, "For God's sake, Colin!" But he could never believe it was a career. But for me, it's definitely what I wanted, yeah. PCC: ARGENT: And then, at the end of it, I got the place at university and decided I wasn't going to go. I did actually send them a letter and I thought it was really fantastic of them at that time, because rock 'n' roll was really looked down on by most people then, certainly in the educational world. I said, "Look, I've got a chance to make this record," because we'd won a competition. "And I really want to give it a go, because I think it's a chance that could well not come along again." And they wrote back and said, "Yeah, go for it." They said, "If you find it's not working in a year's time, do get in touch with us again." So I thought it was fantastic at the time. But anyway, I told my parents what I was going to do and they sat me down, because they'd been through all this sacrifice, and they said, "Are you sure? Are you 100 percent sure this is what you want to do?" And I said, "Without any question. I've got absolutely no doubts about it." And they said, "Okay, we're behind you 100 percent." They were fantastic. PCC: ARGENT: We weren't ever thinking, "This is going to be commercial, so we better do this. Make sure you get the hook in at 40 seconds" or something like that. We never thought that, ever. We just followed, "Hey, why don't we try this? Did that sound good?" "Yeah, that's great." "Let's do this!" And we would just do that. And I think, in the short term, it was often a real disadvantage to us, because we weren't just trying to hitch ourselves to the coattails of fashion. So we weren't saying, "Oh, this has been a big hit record. Come on, we'll get a hit record, if we do this." We never thought like that. And in the short term, I think it often meant that nobody thought that what we were doing was commercial. And it was difficult for us to get radio play. But in the long term, I think it's what, to our complete astonishment, has meant that 55 years later, some of the things that we were doing then are still being discovered by people that are 18 and 19 years old. And the thought that we could relate to people of this generation, as well as people who have followed us all the way through, was unlooked for and incredibly gratifying. But I do think that's because we were just honest to ourselves. We just got excited about making something work. And I think that's what we still feel. If I write a song now and we start rehearsing it and it starts to work, it just feels very exciting. And that's where a lot of the energy comes to you from. And it feels a real privilege to be able feel that way. And it's something which very few people can say now. I mean, most of the people that I grew up with in school have retired now. And I'm not saying they're unhappy or anything, but they're just sort of winding down. And sometimes the tedium of being on the road certainly gets to you, as you get older, particularly. But that feeling of being on stage and having people of all ages in the audience relating to you and sending back energy to you and making you feel absolutely as you did when you were 18 years old, is a real privilege and something that's a fantastic bonus as you get older. PCC: ARGENT: So I put on a John Lee Hooker record. And the first song on the album was a song called "No One Told Me." Now I rush to say that, apart from that phrase, "no one told me," there was nothing in either the lyrics or anything in the melody. His melody for "No One Told Me" was nothing like my song. But I just liked the way that phrase tripped off the tongue. And I started weaving a story around that phrase and just let it develop naturally. And the notes to "She's Not There" are completely based around a blues scale. The melody is based around a blues scale. But as I've already said to you, the chords that came along to me were fashioned in a way that I'd been influenced by Miles Davis without even realizing it. So that became a little bit a part of it -- the indirect influences. My love of harmony was there within the song. And even though I didn't even think about this at the time, the piano solo in it, which was very unusual, I guess, for the time, came naturally, because I'd listened to so many people improvising. And I have to say, you can listen to alternative takes of "She's Not There" and the solos are totally different each time. So it wasn't worked out. It was out of that excitement of improvisation, basically. So that's where it came from. And we just thought we were being The Beatles, but in the end, it turned into something, when I go back and listen to it now, I don't think it sounds like anybody else. And I think it's because of all these things just coming together. And because we were always honest with ourselves and always just got excited about making something work. PCC: ARGENT: And then about another half-an-hour later we had another break for a coffee. And Colin started strumming a Rick Nelson song and we still can't remember what it was -- it was probably something like "There'll Never Be Anyone Else But You" or "It's Late," one of those, because he was a real Ricky Nelson fan. And I can still hear a bit of that in his voice, actually. And I was completely blown away. I said, "You sound great!" I said, "I'll tell you what, you've got to be the lead singer and I'll play piano." And that happened on the first rehearsal. That was 1961, the first rehearsal. It was '64 -- and by that time, we'd built up a real local following - and we got the record. And for the record, I deliberately -- because I was knocked out with his range and his intonation, which quite naturally at the age of 17 or 18, was fantastic -- so I deliberately wrote with his voice in my head and tried to exploit his good range... which he never thanked me for, because what it meant was, on "She's Not There," [sings] "Well, let me tell you 'bout the way she looked... " And the really high notes at the end, all on one note, it's all very well to do that in the evening perhaps, but we were doing sometimes nine o'clock in the morning BBC radio sessions and he'd always curse me, having to hit those really high notes first thing in the morning [laughs]. But it's true, yeah. And in The Zombies, like "Odessey and Oracle," I always wrote parts, and Chris [White] did, too, like when Chris wrote "Brief Candles," he had me starting off the first verse and then sang the second verse and then Colin -- we would do those things, too. But generally Colin was the lead vocalist and when I start to write something today, I've always got this sense, quite naturally now, because I've been so long with him, about where his voice will be. So I do think about his voice, yeah, but without consciously doing it. It's just there. PCC:

ARGENT: And "Time of the Season" was written after hearing Burt Bacharach use those sorts of chords. So yes, he was most definitely... you know, I didn't try to copy any of his chord sequences or anything; it was just the way he used those more complex chords within the music that he was doing. PCC: ARGENT: So there was a feeling of things being very possible. Suddenly there was a huge explosion of possibility in every way. And the other thing was that, culturally, there was music coming in almost solely from America, in all its forms. But we didn't have the separation of radio channels that you had over here. There was very little music on the radio, to be honest. But merchant seamen would go to New York on the ships and they would get off at Ellis Island or wherever the Statue of Liberty is, and just walk up Broadway and visit all the record shops in New York. And they wouldn't think in terms of "I listen to black stations" or "I listen to jazz stations" or "I listen to country & western" or "I listen to white stations." It was just everything that excited them, they would bring it back. And they would feed it back through Liverpool, which worked so well for The Beatles, of course. And then, that of course, was all filtering down to London. And it was a wonderful time for the explosion of every sort of music, for rock 'n' roll, for blues. And there was no distinction. The black population basically getting very excited about the urban blues -- you know, Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley -- and they'd already left behind, discounted people like Muddy Waters or John Lee Hooker and a myriad other, more country blues artists, because they were suddenly saying, "Well, that was yesterday, you know. And now we've moved on to this." But there were none of those distinctions. So all this huge melting pot was coming back. And coupled with the fact that suddenly there was an increase in money and a relaxation of all the sort of strictures, it was just a fantastically explosive time. And everything was there to be discovered. It was such a great time in music... and to be that age. Anything seemed possible. Also, a lot of the rock 'n' roll bands were listening, like I was, to different sorts of music. John Steel, The Animals' drummer, said to me that when he was playing "House of the Rising Sun," he was imagining that he was playing the rhythm part to Jimmy Smith's "Walk on the Wild Side." So those things were just swirling around. And then, obviously, The Beatles, again, when they crashed open the doors to America, it seemed like a miracle to us. And there we were, right at that moment, making our first record. We sort of tumbled in behind. It was a fantastic piece of timing for us. And very, very exciting for us. It was an explosion of everything. PCC: ARGENT: But we walked into the Fox and we were so daunted, because on the bill was Patti LaBelle, Ben E. King, I think The Shirelles were on. I mean there were all these fantastic artists, some of our real heroes. And we thought, they're going to just think we're coming over and copying their music. And they're going to think we're five skinny white kids giving a pale imitation of what they do so much better. And they're going to hate it. They didn't. I mean, Patti LaBelle was a star. And we had long talks with her. And she would talk with us about Aretha Franklin. She said, "You've got to check out this new kid on the block, Aretha Franklin." And Nina Simone, who we'd never heard of. And that side of things was magical. We were kids. We really were. We were 19. We were kids. And so it was all an extraordinary experience. PCC: ARGENT: But my memory of it is that he was a monster to most of the people involved in the filming. And, of course, their careers depended on him, in way. We didn't care. But he really scared them, because they had to defer to him all the time. I just remember [chuckles] he was filming a little bit with me. I mean, I'm not in it very long [laughs], but there's a bit with me where my face fills the screen. He was doing that bit. And he said something really rude, I thought, to me, as he did to everybody else in the cast. And I said, "If you ever talk to me like that again, I'm going. I'm just going to leave." And he just looked at me and he burst out laughing. And then after that, he was nice as pie [laughs]. But the thing is that we didn't depend on him in any way and I thought, "If you're going to be that way, we don't need to be here. We'll just go." [Laughs] PCC: ARGENT: I loved the thought of longevity, but we didn't really think that was in the cards. I remember my dad saying, as I said to you before, once I said I really wanted to do it, he and my mum gave 100 percent approval, but my dad said to me, "You've got to realize, this rock 'n' roll thing is only going to be around for a few years." And yet it's lasted longer than any other form of popular music [laughs]. But we just didn't believe it at the time. And I would never have thought that any of the pieces of music that we were constructing them would have had the longevity that they've had. I really wouldn't. PCC: ARGENT: But we constructed that first album on the back of a hit single. We didn't have enough material. The whole thing was recorded in two days, including mixing. And that's how things were done then. And it came on the back of hit singles. Later, much later on, after we'd broken up, we found out that there was almost never a time when we didn't have a hit record somewhere in the world. But the world wasn't constructed like that in those days. I mean, things took forever to find out. Nowadays, with social media, it doesn't matter what part of the planet you're on, the news will get through in five minutes and you will know. In those days, it was a big deal to travel. We spent most of our time in the UK. And, in the UK, we had less success than anywhere in the world. And so we only ever had one hit single in the UK [That was "She's Not There." Though a smash in the America, "Tell Her No" only reached number 43 on the UK charts]. So there was never a call for an album. In the end, we got very frustrated with the production on our singles. And it was in the air that we were going to split up. We always put demos down and the demos always sounded more true to our ideas than the final singles were. So Chris and I said, "Let's go to a record company and say we want to produce an album ourselves. Let's get out our own ideas of how the songs that we're writing at the moment should sound. Let's get that on record, particularly if we're going to break up. This might be our last chance to do it." And that's why the second album, "Odessey and Oracle" was made. We went to CBS. They gave us a thousand pounds. And we had to do it within that budget. So really, there was never a call for an album without a hit single in those days, in the mid-60s. And we'd only had one hit single in the UK. PCC: ARGENT: We recorded each track very quickly. We recorded over a six-month period or more. But that wasn't six months of being in the studio. It was a few sessions here and there. And we were writing as we were recording. I don't mean in the studio. I mean between recording tracks. And we were excited to have our own ideas. Also, we were very excited about the fact we had a few more tracks than we'd had up to that point. We rehearsed and really prepared before we went in. We would typically record a track in a couple hours. And then, because there were one or two extra tracks, any ideas that just spontaneously occurred to us in the studio, we'd whiz in and put an extra harmony on or add a keyboard part with the mellotron that The Beatles had left behind, after recording "Sgt. Pepper." And it was a combination of being really, really prepared, because we were so excited about the chance to do that, and a feeling of freedom and spontaneity, because we had a few extra tracks. So it was, again, a magical combination. And at the end of it, we felt that we'd got something good and we felt it was the best we could do at the time. And it got really good reviews, but nobody heard it. I mean, nobody played it. So we split up. And then, of course, 18 months later, a single DJ in Idaho played it and, in the way that things happened in those days, things could take six months to build. And it did. And it got to number one in Cashbox, number two or three in Billboard. It was a huge hit. And it was number one in most places in the world, "Time of the Season," but it's been released about five times in the UK. Never been a hit, even though it's still being played on the radio in the UK all the time. And, again, kids know it. I don't know how, but they do. We played at Glastonbury about three years ago. Not on the biggest stage, but we still had about 5,000 people. And when we played "Time of the Season" they didn't only all go mad, but they were singing along to everything. And these are 18, 25-year-old young people [laughs], substantially, at Glastonbury at that time. And some older people, as well. But it's never ever been a hit in the UK. But it seems to be known by everybody. PCC: ARGENT: And, again, it was very interesting -- it wasn't like anything else that was around. I mean, for God's sake, a pop song with a sort of jazzy type organ solo in the middle. And at the end [laughs]. You'd never think it. But it was done very quickly. My memory -- Colin disputes this really. We remember things differently -- my memory was that Paul Atkinson [Zombies guitarist] had already said, "I'm going to split. If nothing happens with this, I'm going to have to go." I'm getting married. I've got no money." And I think Colin was then disillusioned and thinking of moving on. And I taught it to him quite quickly. And then we were in the studio. He was putting the lead vocal on and I was doing what I normally doing, saying, "Colin, could you just phrase that phrase a bit differently? Could you just do this and this and that?" And he got pissed off at me doing that. He said, "If you're so f-cking good, you come and do it!" I said, "Now, come on, Colin. It's the last track. It sounds great." And he finished it [laughs] and he's aways said, "I'm so glad I did." PCC: ARGENT: Again, this was just us trying to be true to what our enthusiasm and instincts felt would be right at the time. It didn't seem right to abandon all that, just to hop on the bandwagon just for money. It's not that we don't want money. But it's never been, as I said before, about us trying to make a hit record. That was never the total motivation, trying to make a lot of money quickly. It was always -- we're doing it for the music first and then, I hope that makes us loads of money, that would be great. That was the reason. We were just being true to ourselves. And then of course, it was only in the last few years that we found out that one of the fake Zombies that filled the gap later became ZZ Top. PCC: ARGENT: PCC: ARGENT: PCC: ARGENT: And that had been our experience with Argent. Not quite as badly as that, but we'd never done great with Argent in the South. And I don't remember us doing particularly well with The Zombies in the South either, not that we toured all that much with The Zombies over here in the 60s. But extraordinarily, about six years ago, around 2012 or something like that, even though our audiences were really starting to build in America at that time, I remember saying to Colin, "Oh, we've got a few Southern dates now. I'm not looking forward to this, because there's probably not going to be many people there." And they were all packed. And since then, whenever we play in the South, we get this big following. [Chuckles] It's really inexplicable. But it makes us really quite proud, the fact that we built this second incarnation, in its cottage industry form, if you like, but to an extent where it seems to be capable of making quite a few waves. So that feels like a source of pride to us now. PCC: ARGENT: And our American management, Chris Tuthill and Cindy da Silva, who are now The Rocks Management over here, who manage us, they said, "Oh, it's our dream to take it to America." And I thought, there's no way, because it's quite an expanded cast, because we wanted to get every single note that's on the original album on there, all the overdubs and everything. But we finally did it in America and toured. And it was wonderfully received. And it was actually lovely. It was almost like that was us continuing our 1965 touring in the States, a sort of fledgling U.S. touring, which was so prematurely cut off in its prime [laughs]. It gave us that chance. And it really felt like we were just carrying on. And, of course, because we were trying to get every part of the album on there, we could include the current band, too. So it was a really nice experience. PCC: ARGENT: And one of the things that I love is that, wherever we play in the world, we can do something like "Time of the Season," which will go down like a complete storm, and then we can do after it a track which very few people have heard, from "Still Got The Hunger," maybe, like "Edge of the Rainbow," and they go crazy about that, too. And to be able to get a response off the new stuff that seems genuine and enthusiastic and not, "Oh, we're just here to hear the old things," that feels fantastic. And yeah, when we got that phone call from Billboard, saying, "We just wanted you to know that for the first time in 50 years as The Zombies, you've got a record in the Top 100 album sales," we couldn't believe it. I mean, it wasn't in there very long, but nevertheless, to actually get that call was fantastic." PCC: ARGENT: PCC: ARGENT: PCC: PCC: And Jim was such an important part of my whole rock 'n' roll life, because he was the guy that turned me on to Elvis. He was four years older than me. So he turned me on to Elvis. He was the guy that was in one of the first electric rock 'n' roll bands in the whole of the south of England. And I idolized him. I was 11. He was 15, playing, and it just sounded magical to me. And that's what made me, first of all, vow that, as soon as I could get some guys together, I'd form a group. He gave me a lift, because I was too young to drive, he gave me a lift to our very first rehearsal, loaned us all his group's gear for the first rehearsal, showed Hugh Grundy, our drummer, the first drum pattern Hugh ever learned -- bass drum and snare. And he was just so important in that way. And then for him to be gone, I still can't believe it. PCC: ARGENT: PCC: ARGENT: PCC: ARGENT: PCC: ARGENT: PCC: ARGENT: PCC: ARGENT: And one of our beefs throughout all our early career was that all the photos that followed us around were awful. They came from the very first sessions we ever did, when we were just straight out of school. And the publicity stories were appalling, as well. And they were the ones that followed us around. We knew we had good photos taken of us during our career, but they never saw the light of day. Well, somehow, our American management and BMG sourced these photos, put together a book, which gave a true feeling of what we were doing and how we looked. And they got all these endorsements from artists -- we had no idea. When I was sent a copy of the book, I opened it and on one of the opening pages, suddenly Brian Wilson has said, "Oh, man, The Zombies really blew me away with 'She's Not There' and 'Time of the Season,' 'Tell Her No,' those great singles. And man, those harmonies, I absolutely loved them." And I thought, "This is Brian Wilson talking!" [Laughs] And then everybody from Susanna Hoffs, who wrote a beautiful thing, to Carlos Santana, Graham Nash [and Paul Weller, plus Tom Petty, who wrote the foreword] and a few indie bands, as well [including members of Cage The Elephant and Beach House], they got these people saying lovely things about us. And it just felt like a real recognition. That was really smashing.

For more on this artist, visit www.thezombiesmusic.com or www.rodargent.com.

You might also enjoy the PCC interview with Colin Blunstone:

http://popcultureclassics.com/colin_blunstone2005.html

Upcoming 2018 U.S. Tour Dates |