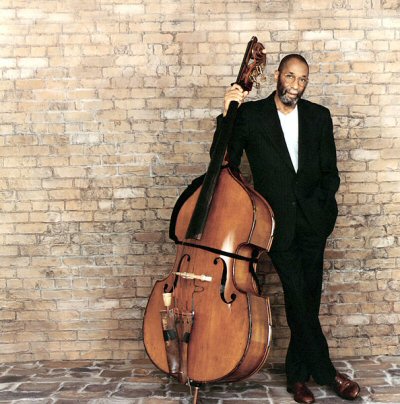

RON CARTER: LEGENDARY JAZZ BASSIST

Well, one of the things I took from classical music was how to practice, how to make lessons productive. One of the things I worry about with my students is they hadn’t learned how to practice, in their limited time, because they’ve got gigs and class work. So their practice time is not as viable as it can be for their progress that they have in mind, that they’re hoping for. So one of the things I took from the classical world, from my lessons for all those years, was how to practice and make the practice time productive. PCC: As a child, what attracted you to music? CARTER: Well, the teacher came in, when I was 10 years old, what would that be - sixth grade? And had the instruments laying on the table. We had orchestra in school. And said, “Take one of these instruments home with you and begin to play it.” So I took the cello, because it seemed like a nice sound to me. PCC: What is it about the sounds of the cello and bass that make them resonate with you? CARTER: I don’t want to know that answer, man. If I do, I’d get discouraged, because I may not be hitting that goal. PCC: What was it about jazz that drew you in that direction, rather than focusing solely on classical? CARTER: Well, the classical world, at the time I was coming up, was not ready to accept an African-American performer in their midst. In ‘58,’59, ‘60. And the jazz world, I was making gigs in college, to help pay for the cost of my education. And they told me, “New York is always looking for a good bass player - you should come to New York.” So here I am. PCC: And did you embrace the creative freedom that jazz permitted? CARTER: Well, I kind of thought that, given the library that I was studying at the time, the Bach cello suites, that I was being creative, despite them not being my notes. I didn’t feel that I was restricted in any form or fashion. Clearly jazz has a different point of view of creativity. It allows you to create and interpret as you see fit, rather than following necessarily in the footsteps of your previous teachers. But I didn’t go out and have a drink, because I was now free. No, I didn’t do that at all. PCC: Beyond the technological advances, how do you feel jazz in general has changed in the past half-century? CARTER: Well, there are fewer places to hear it and fewer places to play it and fewer places to buy it. Three reasons why it’s changed. PCC: Why do you think that’s the case? CARTER: Well, they've made machines available - now the new Mac machine doesn’t take CDs. So you can’t buy a CD and play it in your machine. Or a DVD or whatever format of disc you have. That’s not available to you anymore. iPhone doesn’t take a disc. iPad doesn’t take a disc. And Mac sold 10 million iPhones last week, man. If they had sold 10 million MacBook Pros, that had the place to take a disc inside, I’d have been jumping up and down, too. But that didn’t help us at all, because all you’ve got to do is press a button and you go to Spotify or Pandora and they’re just stealing music and playing it without allowing you the pleasure of going out and buying a CD with the whole story on the CD. So that’s probably the biggest negative influence that the electronic contention invention has on our world today - on my world, specifically. My limited experience has shown me that most of the jazz lovers that I grew up with are not interested in the new technology that makes them not be able to go out and buy an LP or buy a CD. It’s not the same fidelity. It’s just not the same kind of bowl of wax, so to speak, at all. PCC: Your years with Miles, what were the most exciting elements of that journey, from your perspective? CARTER: Playing with Miles and Wayne and Herbie, George [saxophonist George Coleman, who preceded Shorter] and Tony. PCC: Just being part of that combination? CARTER: Absolutely. PCC: Was that a wide open time of discovery for you? CARTER: Discovery is always available to someone who is attentive to getting better. That was a special group of guys that all had the same level of intensity of getting better. That may have made them maybe more special than the other people I have played with. But again, every time I play the bass, I learn something from whoever’s in the band. It’s like a free school for me. I’m not trying to diminish the importance of that group, but everybody I’ve played with, I’ve been able to learn something from how they do music. PCC: What most impressed you about Miles, as an artist, as a man? CARTER: Every night was a chance to play wonderful music. Don’t pass it up. PCC: That was his philosophy.

Yeah - for me, that was his philosophy. I’ve carried that with me - right up through last night, as a matter of fact. PCC: Playing on well over 2,000 recordings, collaborating with so many artists in so many settings, is that the key to your continuing growth as a musician? CARTER: I think the more you get a chance to play, the more you get a chance to experiment with ideas and compare ideas with people, live, on the spot, you get a chance to see - if it works for them, will it work for me? And if it doesn’t work for me, what I can fix, in the short haul, to help this project to become more successful? Because they expect me to be part of the musical success of this project. Then when I’m done with it, can I look back and find out - what can I borrow from this person’s concept or their writing skills or their musical direction, to make what I want to do - whatever that is at the moment - better? PCC: Working with a vocal great, like Lena Horne, in that kind of complementary role, do you enjoy that as much as a gig where you get to explore a groove more freely with other instrumentalists? CARTER: Paul, I play freely with everybody. That’s what I’m hired to do. They hire me to do what I do, however you define that. And sometimes I kind of resist the word “freely,” because that implies that I’m playing with no boundaries and I’m just kind of making people do what I want them to do with no real regard for the musicality of the piece, the tempo, the stuff. I’m a very disciplined player. And ‘free” to me doesn’t really fit what I’m trying to do. I feel free to play what I play. But I do have my set of rules and restrictions that allow me to, I think, be a more complete musician and therefore more open to more choices and possibilities. PCC: Stepping into the role of band leader, was that a natural transition to you? CARTER: I think every bass player gets tired of taking directions, whether he agrees with him or not. That’s the natural dissolving of the enemy, so to speak. [Chuckles] So being a leader was something that I thought I had to experience. And I’d had enough band leader lessons from other leaders that I thought I could be a very good one. PCC: And who were the leaders you had worked with, who were particularly valuable in helping you see how that role best works? CARTER: All of them. They all had something different, a different point of view, a different way of handling stress, a different way of building the sets, a different way of audience awareness, a different way of tempos, a different way of keys. They all had something different. I hope I picked up enough hints from all those people to make me the kind of band leader that could bring together musicians who would want to follow my tracks and allow me to share what I learned with them. PCC: That quote on your website: “The bassist is the quarterback in any group,” can you elaborate on that? CARTER: He’s the only one that plays everything all the time. He plays the meter. He plays the changes. He plays the notes. He plays the intonation. He plays the dynamic. He plays the dynamic as far as the volume is concerned, the dynamic in terms of the direction of the song. He’s the only one who plays these things for every note. And clearly for me, with that responsibly comes a leadership, being able to lead the band in the direction that you feel they can best function. Quarterbacks all do that, whether it’s a quarterback on the football field, literally, or a point guard in basketball. They all do that, man. And it’s a chance for them, for bass players, to really enjoy being responsible and being the focus, albeit a quiet one, of the musical direction. PCC: Composing, is that for you, is that a combination of combining the analytical and the intuitive? CARTER: I'm always interested in being involved with a melody sound and how they work and are these the best changes for this melody? Can I have some other changes? And maybe they led to another melody. Those kind of scientific possibilities have always interested me and I’m taking the time, more now than I did before, to sit down and just compose some pieces on my own, to see if what I hear happens on paper. And if I can convince someone else that they sound okay, then they can play them, too. PCC: Do you wait for the muse? Or do you tell yourself it’s time to write? CARTER: I sit down and say, “I have an hour to write. Let me see what I can come up with.” I like that kind of discipline. PCC: And the playing - is that a mix of the technical virtuosity, mental focus and the soul, emotion? CARTER: Yes, all of those things. As a teacher, you know all that exists. You teach things along those concepts. But I think, when they’re happening to you, you’re not so aware of them. You’re just kind of along for the ride, knowing that it’s going to be a great one. PCC: Your role as educator, has that been especially gratifying for you over the years? CARTER: Oh, yes. I have some students that are doing the music world proud, I think. PCC: And it’s important to you to pass along all you’ve learned? CARTER: Well, you know, every teacher has their own propaganda, I call it. And they look for someone with whom to share these ideas and thoughts. I’m no different than those teachers. Absolutely. PCC: What is one of the key things you want to share, besides the technical aspects? CARTER: That you have to understand that there’s someone playing besides you. And how can you make them better? PCC: Are you optimistic about the future of jazz, in terms of it surviving, thriving, growing? CARTER: It’s going to survive and thrive, despite the environment right now, which is not specifically encouraging to music. And I don’t mean just the universities that turn out these kids. But there’s always been this current in the city of New York, where guys want to see, “What will happen, if I play this chord right here?” Or “What happens, if I play this volume?”Or “What happens, if we have a group of this size and this instrumentation?” Those people are going to be around, because that’s what evolution is. So I have no fear that jazz is going to disappear, man. I think that’s not possible. It’ll be here until the last person is here, man. PCC: There will always be the curious and the adventurous. CARTER: Absolutely. All you need is something to bounce sound off. Like a wall. Or a glass of water. I saw it the other day in a catalogue, a water glass, they had marked on there with rings, that you put water up to this point, you get these notes. People are going to find things to make instruments out of and despite not having a Stradivarius available or an upright, they will find things to make sounds and with these sounds will come curiosity. “If I put this sound over here...” Or “If I cover the sound like that...” Or “If I change the sound like this... how is it going to affect my community?” Those people will be around forever, man. They came here before I got here. And they’ll be here long after I’m gone. That’s how music exists. And that’s how jazz is going to be around. PCC: What have been the greatest rewards and the greatest challenges in your life as a musician? CARTER: The challenge is just to keep playing the music, despite everything else that doesn’t encourage me to keep on - like fewer clubs. And no major jazz record labels. Those kind of events make it difficult, not just to earn a living, but to be a part of a community that was in existence, that’s no longer there anymore. PCC: And in terms of rewards? Is it just about making music that excites you? Interacting with your peers? intriguing the listeners? CARTER: What affects me is, I go to work hoping that, one, I can make this person sound better. And two, how much can he show me that I don’t already know? That excites me every night. PCC: And with all your accomplishments, any yet to be fulfilled goals, musically? CARTER: Well, one of my goals is to come home at night, feeling that I’ve played the best I could. And that’s always been important to me, with whomever I’m working, whether it’s a recording session or a nightclub gig or a concert, when I finish this event, I can look in the mirror in the morning and say, “Gee, kid, you played the best that you could” and feel comfortable that that’s the fact of the matter. Do I have any ambitions? Just to be able to continue to help someone play good, man. I mean, that’s what bass players seem to do as a career. I don’t mind being in the role of saying, “I helped this guy.” I like that feeling, man. For more on this legendary musician, visit roncarter.net. |