|

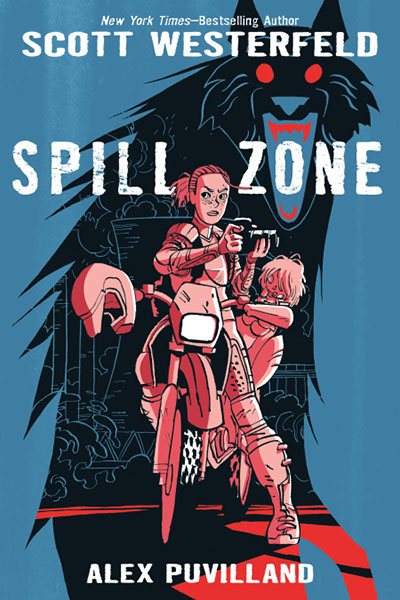

SCOTT WESTERFELD PCC Talks with the Bestselling Author about “Uglies,” “Leviathan” and his latest, “Spill Zone”

By Paul Freeman [April 2017 Interview] It’s the near future. Poughkeepsie, New York has been left in shambles. Addison, a motorcycle-riding, teen photographer lost her parents in the mysterious tragedy. Her young sister also survived, but doesn’t speak, though her disturbing doll does. To earn money, Addison darts through the forbidden Spill Zone at night, snapping pics, averting terrifying manifestations and potentially fatal dangers. That’s the premise for “Spill Zone,” the newest work and comics debut from author Scott Westerfeld, whose previous Young Adult book sensations include “Uglies” and “Leviathan.” “It’s about how nice, working-class towns can end up on the trash heap of history,” Westerfeld says. “Towns die all the time, for various kinds of reasons. I’m just doing a more dramatic version of that.” Westerfeld, who has earned fans among both YA and adult readers, went to college in Poughkeepsie. “While I was there, I used to do a certain amount of what I guess you could call ‘urban spelunking.’” He climbed around the steam pipes of college buildings and snuck into the city’s abandoned mental hospital. That ended up being stirred in with what he was reading about the aftermath of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster. “In the early 2000s, people were exploring the Chernobyl exclusion zone, taking pictures. I remember one photo that showed a school room and all of the text books were opened to the same page. They had been left there when the students evacuated. And this was like 20 years later. “So it was this idea of a town that gets obliterated suddenly and is abandoned and strange artifacts are left over. So I imagined these things happened in Poughkeepsie and a character dealing with that loss.” Though it’s filled with suspense and action, including motorcycle thrills, “Spill Zone is primarily about loss. Westerfeld says, “It’s the combination of a personal loss - she’s lost her family - and a larger, more global kind of loss, like when you lose an industry or a town or something like 9/11 happens. What’s going on in ‘Spill Zone’ has its own cosmic significance, because it may be due to aliens, people from another world or another dimension. But these big situations also have personal consequences. “It’s about what you lose, when you lose your hometown and your history and your family. Families are like little mini-cultures. When you lose your family, it’s like Krypton blew up - nobody speaks your language anymore. The customs, that special little language that you had - all of its gone. So what Addison is trying to do is to keep what remains of her family - her silent little sister, she’ll do anything for her sister. At the same time, she’s trying to deal with her loss through making art. So it’s the pairing of holding onto what you have, but also exploring what you’ve lost.” In his books, Westerfeld displays a knack for creating indomitable female characters like Addison. “I find it fairly easy. I have two older sisters, one of whom was definitely a badass. She’s still, at the age of 57, climbing in caves and climbing mountains, doing all kinds of silly, scary stuff. Every time I hang out with her, she tells some sort of terrifying story of almost dying, because, for instance, she and her boyfriend ran out of rope in some subterranean nightmare place. So it’s never been difficult for me to envision strong female characters. “I also like writing female characters just because I feel like, to generalize, teenage girls are more willing to explore their interiority. They do spend a lot of time figuring out what they’re thinking and why they’re thinking it. And that’s easier for me to write. There are YA writers like Chris Crutcher who are very good at teenage boys. But that’s really not my forte. “One of the things I like about graphic novels in general is that people will read stuff in graphic novels that they won’t read in prose. For example, I’ve seen boys who only read boy characters, like 11-year-old boys who won’t read a prose book with a girl character, but they’ll read ‘Babysitter Club’ graphic novels, because they’re comics, so it’s okay.” His “Leviathan” trilogy, a steampunk retelling of World War I, includes in its cast of characters, a girl who, disguised as a boy, flies in the British Air Service. It’s on its way to becoming a TV series.

“Leviathan,” which won the Locus Award for Best YA Fiction, used extensive illustrations by Keith Thompson. Thompson’s ideas sparked new ideas for the text. Westerfeld enjoyed that collaboration so much, a graphic novel was the logical next step. There was a similar synergy with “Spill Zone,” as artist Alex Puvilland (who works with DreamWorks Animation) designed dramatic graphic novel panels. “When you’re storytelling with a strong visual component,” Westerfeld says, “you have to think about issues of scale and light and action and repose and all of this stuff that artists deal with. Just the simple act of creating contrast on the page guides your storytelling in interesting ways. “Alex saw a completed script first, but it changed while he was drawing. He would occasionally request that we spend more time in a location. There were a couple of scenes he thought would be good to add, because it would make the storytelling more complete.” Graphic novels require a far greater economy of words than standard prose. Long speeches cut into the space the artwork needs. “I tried to create as many taciturn characters as possible,” Westerfeld says with a laugh. Westerfeld, whose supernatural novel “Afterworlds” may also soon be making its way to the screen, grew up on Marvel comics - he was a big Daredevil fan - and lately has been reading a lot of Manga comics, “Saga” and Oni Press graphic novels. He wrote a first draft of “Spill Zone” back in 2006. “Some friends of mine who write comics looked at it and I realized from the comments that I didn’t really know what I was doing.” When, in 2012, Del Rey Manga publishers created a graphic novel based on his dystopian “Uglies” trilogy, Westerfeld collaborated closely with an expert writer of comics. “Basically, I tricked them into paying me to learn how to write comics from Devin Grayson,” Westerfeld says with a chuckle. “Then I went back to the ‘Spill Zone’ script - and this is the outcome of that.” “Spill Zone” is aimed at readers 12 and up. Westerfeld has also just launched another new novel, “Horizon,” designed for middle-grade kids, ages nine to 12. The first in a seven-book series, it’s about kids who are stranded in a strange, supernatural land, following a plane crash. Westerfeld enjoys writing in series form. “Especially in science-fiction and fantasy, where you’re spending a lot of time in world-building, it makes a lot of sense to stay in that world once you’ve built it. That makes it enjoyable for readers and good for you. It means you can explore things a little bit more. It’s just natural for science-fiction writers to write in the series form. It’s what I grew up with.” Growing up, reading and writing were essential to his surviving adolescence. “When I was young, there wasn’t really a YA book section as much. I feel like the science-fiction section was my YA section. The colors were brighter, the covers were more awesome and people were doing stuff on the covers that I wanted to do.” Questioning authority is a recurring theme in Westerfeld’s writing. He grew up identifying as an outsider. “I moved around a lot as a kid. My Dad was a computer guy in the 60s and 70s. So he was moved to all these places where computers were needed. So we lived in Houston for NASA. He worked in Palo Alto for aircraft. We lived in Connecticut for submarines. I was like an aerospace/industrial complex brat,” he says, laughing. “And as such, I was always coming to a new town, going to a new school and kind of introducing myself and inventing myself. The idea of being a fictional character myself was pretty easy for me.” Essentially, Westerfeld is now writing what he would have enjoyed reading, when he was a teen. “It’s also fixing things that I thought were annoying and wrong.

As for writing YA, Westerfeld says, “People always talk about what you can’t do in YA, like they think that’s the thing that changes it, the limiting factor. But I always think more about the fact that there’s stuff you can do that’s harder to do in Adult. For example, I do this test occasionally - I’ll have a bunch of kids and a bunch of adults in a room. I ask how many of them have memorized the lyrics to 100 songs. The kids all say yes and the adults, maybe a few of them say yes. I ask, ‘How many of you are studying a foreign language?’ The kids all say yes. And the adults don’t. I say, ‘How many of you made up slang in the last month?’ ‘How many of you call your friends by nicknames?’ “And any sort of question about language and about acquiring and adapting and creating new languages, the kids, the younger people, teenagers especially, are always the ones who are doing that as part of their daily life and daily discourse. And writing for that audience is such a great thing. When you, as a writer, are introducing new slang and new words, they’re much more adaptive. So that’s what I like about writing for Young Adults and teenagers. They’re doing cool stuff with language every day in their lives.” Before finding success as a writer, Westerfeld worked as a substitute teacher at his old high school. He also worked as a textbook editor and wrote educational software. Westerfeld, 53, divides his time between New York City and Australia, homeland of his wife, fellow YA writer Justine Larbalestier. He likes juggling different projects at once. “It’s fun to be able to go back and forth. When you’re stuck on one thing, it’s good to be able to pick up something else.” Working in the supernatural and science-fiction genres, Westerfeld can slip in snippets of social and political commentary. “That’s something that people have been doing for a long time. One of the inspirations for ‘Spill Zone’ was the Strugatsky brothers, Boris and Arkady Strugatsky. They wrote a book called ‘Roadside Picnic.’ They do a pretty good job, as does Stanislaw Lem, under the Soviet regime, writing what they wanted to write and communicating interesting things without the censors being particularly aware.” Westerfeld’s work has had profound effects on readers. “Uglies,” in particular has resonated. It depicts a future in which cosmetic surgery is compulsory at age 16. Everyone must conform. Teen readers who have felt ugly and excluded, feel validated by the books. “Just yesterday, I was doing a signing in Chicago and a young woman came up to thank me for helping her survive high school. That happens all the time. People, especially girls, who felt completely erased by the high school experience, found just the idea that someone was not only voicing those thoughts, but putting them into a narrative and showing a survivor dealing with that world and fighting against that, they found that very helpful. It’s not necessarily what I was intending. With ‘Uglies,’ I wanted to kind of rewrite a classic science-fiction story and get some details right and have it make more sense to me. That’s what I was doing. But the end result was that the story still holds up. People needed it for a new generation.” Westerfeld relishes the interactions with fans at book store events and conventions. Like many of his works, “Uglies” has a worldwide following. “It’s one of the best things about being published, is that you learn all this stuff about the way readers read and what they see and don’t see and the stuff that’s in there that you didn’t realize was in there. It’s an amazing thing to have written a book that’s read by millions of people. It’s been published in 35 countries. “Just seeing all the different covers that are put on it is kind of weirdly instructive. Every market has its own way of advertising this book and communicating what it’s about. I find that fascinating. “I really do enjoy book store events, where I do get fans who are from 12 years old up to 50 years old and all are there to celebrate a book or to talk about the same stuff, to laugh at the same jokes and to know the same world with each other. I think that’s really cool. One of the things about books like ‘Uglies’ and ‘Leviathan,’ they have their own language. And hearing people speak that language and knowing that they share it or they made someone else at their cafeteria table at school read that book, so that they could talk in that language, that’s all very exciting and edifying… and cool!” Another great reward comes with the completion of a new work. “I still love finishing a book or getting to the point where I know I’m going to finish and knowing the end is there. I love being at the end, at the last few chapters, where I have all 80,000 words swimming around in my head. I have no brain space for anything else. I can’t pay bills. I can’t worry about politics. I’m just full of the book. And that’s a great feeling. Westerfeld is working on “Spill Zone 2,” as well as a still secret project, another series. The ideas never stop buzzing. “I think most writers die with only half their books written.” For more on this author, visit www.scottwesterfeld.com. |