|

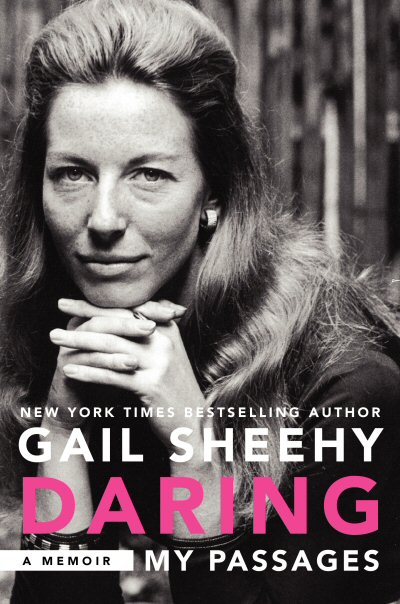

GAIL SHEEHY: A DARING JOURNEY THROUGH HER PASSAGES

By Paul Freeman [September 2014 Interview]

As a ground-breaking journalist, Gail Sheehy, acclaimed author of “Passages,” has examined many of the world’s most remarkable people. She has now brought us an illuminating exploration of her own rich, dauntless, inspirational life - “Daring: My Passages.”

The new memoir is a wonderful read, moving and insightful. She had reached the point where she was ready to turn inward.

And Sheehy has a daring and fascinating life to draw upon. The persevering Sheehy broke down barriers in the male-dominated world of journalism. She contributed to what Tom Wolfe dubbed the New Journalism, writing memorable articles for New York magazine, the London Telegraph, Chicago Tribune and other top publications.

Talking with such world leaders as Hillary Clinton, George W. Bush, Margaret Thatcher, Anwar Sadat and MIkhail Gorbachev, covering events like the Bobby Kennedy presidential campaign, Sheehy became a participant in history.

The author of 16 non-fiction books and a novel, Sheehy has received numerous prestigious awards. Readers related, in profound ways, to her 1976 book, “Passages,” which investigates life’s transitions. The LIbrary of Congress named it one of the 10 most influential books of our times.

Sheehy has always relished tackling difficult subjects, from civil rights to violence against prostitutes to menopause. She feels compelled to bring them to light, sparking a dialogue. In recent years, she embraced the role of caregiver during her late husband, famed editor Clay Felker’s long battle with cancer. She was then able to put her experiences on paper, elucidating those difficult passages.

Now in her 70s, the vibrant Sheehy continues to inform and inspire.

POP CULTURE CLASSICS:

What led you to decide this was the time time for a memoir? And did you welcome the new challenges this form presented?

GAIL SHEEHY:

[Laughs] Well, I didn’t know what I was getting into. Gosh, I’ve spent decades interviewing probably thousands of women and men about the stages of their lives and their predictable crises. And it was about time to put the lens on myself. It only seems fair. And I really hadn’t taken a deep look at my own life, but I thought, this is the time, I passed 70. And if nothing else, it will be good for my grandchildren. I really had no particular hopes for it being of value to others. But I did have a friend who kept taking me out to lunch and dinner, drawing stories out of me and saying, “You have a fascinating life - what are you talking about!?”

So I embarked on the hardest excavation I had ever done of anybody’s life and found it very challenging and also often delightful. I would spend days writing about some period of New York Magazine or being with my family or Vanity Fair or the romance and break-up and coming back together with Clay. And I would be living there. I was just reliving the life. And that was quite wonderful. And the sad parts were very sad, but it helped to heal a lot of raw nerve endings, I think.

PCC:

In the process of writing a memoir, did you gain new perspectives, insights, into your own life and your psyche?

SHEEHY:

Well, it wasn’t until I came close to finishing the book that I saw the theme of my life. And it came out in this one word - daring. I hadn’t really thought of that before. But then it seemed to string everything together that was important in both my personal life and professional life.

PCC:

Looking back, this daring, this ability to turn fear into a positive, where do you think that came from? Was it inherent to some degree?

SHEEHY:

I think it is partly inherent. It’s like everything else - it’s partly genetic and partly the experiences you have, particularly in childhood. And I remembered my grandmother being my rock in an otherwise chaotic childhood experience. And I tell that story about her giving me a typewriter, when I was seven years old. It thrilled me. I could tap out, I could rewrite Nancy Drew mystery stories. And then when I was closer to nine or 10, I started wanting to live the radio show that my grandmother and I used to listen to together - “Grand Central Station: Crossroads of a Million Private Lives.” And it so thrilled me, the idea of these exotic lives that would criss-cross in this metropolitan epicenter, so different from the suburb where I lived. I couldn’t wait to get in and find other stories.

So my grandmother let me take the train by myself, gave me a little money, kept my secret. And I couldn’t even climb up on the washboard trains they had then, with very tall steps. Somebody would give me a push And then we would come to Grand Central Station and I’d run up to the balcony and look up at the cosmos embedded in the ceiling and then look down at these people and imagine their stories. And it just made me feel so important, that I could be a fly speck on the balcony, with a pad and a pencil and write down stories. So I think doing that and having some appreciation, by both my grandmother, and later, my father, was very encouraging.

But as it turned out later on, when I started writing professionally, and this didn’t come to me until I had written the first draft of the childhood chapter, I had thought of my father as being really my earliest coach. But he stopped once I started writing professionally. I had written about him in a very rose-colored way. And my sister read the first draft of that chapter and said, “But don’t you remember, once you started sending magazine articles, and then all the books that you sent? Our father never read a word. Not a word. Because you were more successful than he was.” And that was startling. So that gave me an insight into why Clay Felker was so important in my life, because my first husband also didn’t show any interest in my writing. But Clay Felker certainly did.

PCC:

You mention in the book how your female college mates graduated and were content to marry well, while you were wired to have ambition, to want more than being a homemaker as your sole role? Did you wonder why they settled? Did you wonder why that wasn’t enough for you?

SHEEHY:

No, I never wondered that, because it had happened to my mother and I saw how shrunken her life had been. I knew she was very talented. She had a beautiful voice. I used to play the piano for her, while she sang. And she was a natural business woman. But in her era, with a man like my father - a sales manager who commuted to New York - women, wives thought they shouldn’t work, because it would show their husbands up as not being successful enough, that their wives had to work. So she spent the time with me. She was wonderful, when she was sober.

She was a wonderful mom. But she was also missing half her life, because she was escaping into alcohol, because of the frustration of not being able to put her own talents out in the world. So I knew I never wanted to be trapped like that. I never would be. And actually, that’s one of the reasons that I was able to marry, even at an age I thought was early - 23 - because I had to have a career, because I was supporting my husband going through medical school.

PCC:

Were there portions of the book that were difficult for you to confront and then reveal?

SHEEHY:

Oh certainly, I’m sure there always are in memoirs. It was very painful to go over the dissolution of my first marriage, to remember how frightening it was to have your life blow up and you’re so young and you really think you have it all laid out. Suddenly it explodes in your face.

And it was painful for me to recall how it tore me apart to go to work - even as much as I loved my job at the Herald-Tribune and later even freelancing - to have to leave my daughter so often, because she had only a single parent now and I wasn’t able to be there for her, even when she was quite young, because that took place before she was three.

So I later wrote about the first bachelor mothers, women who were electing, in the late 60s, early 70s, to have babies on their own, which is now so very common. In fact, it shocks me to think that 41 percent of women under 30 who have children do not have a father in the household. And this is not healthy. I can tell you from personal experience. So that was painful to go over that and say, “Could I have done this differently?” Well, I had to make a living for us.

I had to support my younger sister to finish college, when my parents broke up. l thought sending my daughter to a private school in Manhattan, where she could get a really fine education and then go to a fine university, was really my greatest goal. And to do that, I had to do more than just earn a living. I had to do well. So there was that pull, that every mother mother who has a career feels. But I was able to put aside some of the guilt that practically every mother feels for not having done enough. As a result of confronting all of that and churning with it and sitting with it and meditating on it, I ultimately said, “What had to be, had to be.”

PCC:

Once you achieved success, were you always conscious of not wanting to get too comfortable?

SHEEHY:

Yes, I was. It’s interesting that you picked that up. I really was. Actually, shortly after the success of “Passages,” Clay wanted to buy an apartment, a very fancy, big apartment on the West Side, which is where I prefer to live. But it needed enormous renovation. It was an apartment that people like the Collier Brothers had lived in. It was a total wreck. And it meant that I would be a contractor for the next couple of years, to put this place back together. And I had now a big advance to write a sequel to “Passages” and I couldn’t possibly imagine being able to be both the contractor who renovates a huge apartment and a writer who seriously researches and writes a major book. So I refused to go along with his plan. He couldn’t believe it. “I’m buying this big apartment for you and me!” I just said “No, I can’t do both.” So I always thought it was very useful to know how to live poor.

PCC:

People tend to be fearful of changes, was it for you a gradual evolution - you learning to embrace them?

SHEEHY:

Oh, no [laughs], every one of them was always a major passage. I had a lot of major passages. That’s why I think the new book is exciting to read, because I was constantly either thrown into daring situations or fearful situations or abrupt changes or life accidents, which we all have. And the major one for me was being in a war zone in Northern Ireland and being next to a boy who was shot in the face, which totally changed my sense of time and thrust me into an awareness of mortality, when I was still pretty young, in my early 30s.

PCC:

In the years between “Passages” and “Daring,” has your understanding of the whole “Passages” concept evolved or shifted ?

SHEEHY:

Well, it started with recognizing that many of the people I was interviewing had not had any external trauma of like being caught in the crossfire of Bloody Sunday. But when they were in their late 30s or early 40s, they too, almost all of them, expressed things that sounded like some kind of a mid-life crisis, suddenly feeling time was running out, the hurry-up feeling. “Who am I really? Have I done enough? The dream of my 20s isn’t working out. Where do I go from here? What have done to myself, being in this marriage that confines me?” So people really didn’t have an idea of how they could break out and change and it would be healthy, it would be normal to have these feelings. And so I found many instances in historical biographies and in many more hundreds of interviews I did. And I also discovered that the few men who were researching the field of adult development - it was only a few -were only studying men. There were men studying the life cycle of other men, as if women just were copies of men. And, of course, that was completely unimaginable.

I had this very funny exchange with Daniel Levinson, a wonderful researcher and writer from Yale University. He had a very rigid thesis, that one had to go through the stages, A to B to C to D. They had to be in sequence. And I looked at him and said, “Dan, if that were true, women would all be crazy, because we go from A to C and then we might do a little bit of B. We might never get back to finishing A, because we’re always adapting to other people’s necessities, our husbands, our children, maybe our parents, bosses. So we just have to piece it together as we can. And the issues for us aren’t the same as they are for me.” And he said, “ That makes sense. You should do that. Go ahead and write that.”

So it was nice to get that kind of blessing from somebody who was a professional psychologist and then to go on and explore, what does this mean for couples? If we’re on different tracks, and we have different stages and different issues during our passages, then will that explain a lot about what happens to couples and the kind of couples crises that come along? And, of course, it did. So it was a long process of understanding and coming up with theories and coming up with accessible language to describe this whole phenomenon. And it turned out that it was very useful that I wasn’t an academic, because I was able to put it in everyday language.

PCC:

Has writing always been a tonic for you, a way to help understand and face transitions?

SHEEHY:

Yes. But I think it’s not like a conscious thing that I do. It’s just, when you’re a writer you have to write - that’s the whole story.

PCC:

What about the choices in writing? You’ve always delved into uncomfortable subjects, opening discussion. Did you feel compelled to make a difference through your writing?

SHEEHY:

Yes, very much so. I always wanted to have an impact on social change. And I didn’t know if you could do that, as a writer. Once I saw that it could happen, when “Passages” had such an impact, then I really wanted to break down other taboos. And they were easy to find. It was unimaginable to me, when I got to menopause myself, that nobody ever mentioned that word. It was like worse than the worst curse word that you could emit. Mothers didn’t talk to daughters about it. Girlfriends didn’t talk to one another. So to write that book and to go out on the airwaves and talk about it was very liberating. I felt that I was liberating a lot of doctors, as well as women themselves to have frank conversations about an event that happens to every single woman on the planet Earth.

And I remember this one very funny instance where, very early in the book tour for “The Silent Passage,” I was being interviewed by a man on the noon news in Cleveland, and the poor guy, his producers shoved this paper under his nose to say, “Now the next guest is going to be Gail Sheehy, who’s going to be talking about... What?!” [Laughs] And you could see he was like a deer frozen in the headlights, when I came on. And he started off by saying, “Menopause, is that like impotence?” I said, “Uh, no. But let’s make an analogy. Baldness - is that like Alzheimer’s?” And he could see where I was going with it. And then we laughed and we got to talking about it in a normalizing way, which was my whole point - let’s normalize what happens to half the population.

PCC:

It must be gratifying, when you go on book tours, to hear from readers you’ve inspired to overcome obstacles, to welcome new challenges and to navigate through their own passages.

SHEEHY:

Oh, it is. I am very often just sitting on a bus and somebody across the aisle will lean over - and often times it’s a man - and say, “I made a huge change in my life and I thought it was too late. I was 45 and it really helped me to read your book and know that it was a good thing to do.” And sometimes it’ll be a waiter or a doorman or a beautician, the woman who’s giving me makeup in the green room. And I cherish those moments and those stories, because, I think, verifying for themselves that they did the right thing is good. And I’m right there to say, “No, I didn’t change your life. You changed your life. That’s the hard part.”

PCC:

How do you view the changing world of journalism - do you see reasons for optimism as well as trepidation?

SHEEHY:

Well, at the moment, we’re in such a period of rapid and breathtaking change that it’s not so easy to be optimistic, because what we’re losing is our history. We’re becoming Twitterized. And when you get your news on a daily basis from Twitter, you don’t ever really have the context of what the big news story is. And that’s what long-form journalism provides. And, of course, there are still outlets for excellent long-form journalism - The Atlantic, New York magazine, The New Yorker and there are others. Some are ProPublica and there are those where people pay for long-form stories.

But for the general population, it’s so easy to just click your way through the superficial news and never sit down and really devour an article of 4,000 or 5,000 words that would explain the why - Why was ISIS able to come up so quickly? And what did they really stand for? And why would Americans go to join this band of demons? What is the attraction? That’s a really important story to know, but that would take a lot of research, a lot of resources to spend the time, a lot of daring to put oneself in the crossfire between Jihadis and their enemies to find out what is the lure. But it’s necessary. We can’t really fight an enemy that we don’t really understand.

PCC:

When you first entered the bullring of male-dominated journalism, were you very conscious of opening doors for those following in your footsteps?

SHEEHY:

Well, I hoped so. I hope that the book is a fun read. People say it’s a page-turner. And that really pleases me. I never would have been happy about that with my previous books, because they were pretty serious. But this, it’s good that it’s a fun read, because then it will excite people to be more daring. And we have to be daring to really make a full life and to be successful in whatever field. You have to be willing to cross the line, break down barriers, whether it’s a color line or crossing an age line and saying, “Look, I can do this job. I may be 65, but I’m the best person you could have.” And to have the daring to fail... and fail early. That’s one of the messages of the book, too.

And when you fail early, you realize you don’t die from it. And in fact, today, failing is just the default position for anybody who wants to invent anything new in the digital age, because it takes a lot of crazy ideas to get the one that actually sticks. So seeing the prospect of failing up to success is important. I certainly found that to be true, because I failed early, too. My first book was a flop.

PCC:

Is there sense of contentment, looking back, saying “I’ve accomplished what I set out to do”? Are there any regrets?

SHEEHY:

Oh, there are always regrets. I mean, you wouldn’t be human, if you didn’t have regrets -”Why wasn’t I better able to prolong a relationship? Or do a better job, being there for my mother and recognize that she was an alcoholic and try to help her, before I was in college? Things like that, we all have. But it’s wonderful to see that this book is being received not just as a good yarn, but as an inspiration to people to be more daring and make friends with risk and be able to laugh at oneself.

PCC:

Are you ready for the passages to come?

SHEEHY:

Well, I hope so. But they’re unknown and unknowable. I bought a pair of three-inch heels. I haven’t worn three-inch heels for a while, because my ankles are a little wobbly. But I’m going to wear them on the book tour. I could step off a curb and break my leg. And I’d have to deal with that. And I would. But it could happen at any time.

And it’s also possible to make new friends at this age, which I love. And I have been doing so. And doing it rather determinately, because, as you get older, some of your friends begin slowing down, and a couple of others of my best friends have already died. So it’s very important to make friends amongst younger people and to continue making friends. For men, too. Because it’s having that companionship, the people you can laugh with, that you can travel with, people who will have your back if you run into antagonists. That’s really an important part of staying alive and staying vital. That and exercising. And if I have to get up at five in the morning to get my few laps in on the treadmill, I try to do it, because I think it really is what keeps me going. It keeps my energy up.

PCC:

In your work, are there goals yet to fulfill?

SHEEHY:

Oh, of course there are. I’m very eager to getting back to writing some character portraits about important figures - another portrait about Hillary Clinton. I’d love to write about Vladimir Putin. That’s a big risk, because there are a couple of women who have written books about him who lost their lives under suspicious circumstances. But we need to understand more about his mind to see how we can outwit him. He’s been pretty good at outwitting the United States so far. And we can’t let that go on.

PCC:

Talking with world leaders, covering things like the Bobby Kennedy campaign, you must feel like a participant in history, rather than simply an observer?

SHEEHY:

I do! I actually do. My literary agent, Richard Pine, made a very funny comment, when he read the first draft of my book. He said, “You’re like Zelig! You keep popping up at all these historical events!” [Laughs] That was a funny image.

PCC:

What a wonderful life and career.

SHEEHY:

It really has been... and it still is.

For news on this author, visit: gailsheehy.com

|